News • Microbiome

Examining the "forgotten organ"

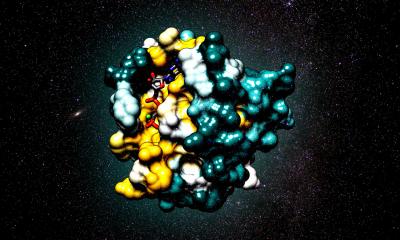

Shahid Umar, PhD, researcher with The University of Kansas Cancer Center, has dedicated two decades of his scientific exploration to better grasp the connection between colon cancer and the human microbiome. Called the “forgotten organ,” the microbiome comprises trillions and trillions of microbes, including bacteria, fungi and viruses, in our body.

Each person has their own unique set of microbes, initially determined by our DNA and early years of life. These microbes set up shop in several areas throughout our body, including sex organs and skin, but the largest concentration by far is in our gut. And the gut, Umar theorizes, is where many diseases originate.

Compared to the relationship between viruses and cancer –such as the human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer–the role of bacteria in cancer development is not nearly as well-established. According to Umar, researchers have only just begun to scratch the surface when it comes to understanding the microbiome. “People think that all bacterial infections can be resolved with an antibiotic. However, you may be oblivious to a microbial issue in your gut at the time it is active,” Umar says. “But the damage is done. Years later, you may get sick.”

Colon cancer, the third most common type of cancer in the United States, can be one such problem. About 85 percent of cases are deemed sporadic, or non-hereditary, meaning there is opportunity for prevention. “That gives us a window to take proactive steps, like eating healthy and staying active, to reduce our risk of colon cancer,” Umar says.

Enter the significance of bacteria in the microbiome. In our bodies, an ecosystem exists in which the gut provides shelter and nutrients for bacteria, and bacteria returns the favor by making vitamins and essential amino acids and processing hard-to-digest foods like soluble fiber. In addition, healthy bacteria help resist infection by pathogens. An unhealthy diet lacking the nutrients necessary for bacteria to thrive may force it to become an opportunistic pathogen. “When that happens, it is harder for your body to resist infection. This eventually leads to incredibly significant changes to your biology, which may surface as colitis, a precursor to colon cancer, or the cancer itself,” Umar says. “My lab has extensive experience in characterizing the role of bacterial infection in these diseases.”

Restoring what is lost

One arm of Umar’s research involves studying dietary factors, primarily a group of compounds called short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), to prevent colon cancer. SCFAs are produced when gut bacteria ferment fiber in your colon, and they are the main source of energy for the cells lining the colon.

One type of SCFA, butyrate, plays a big role in colon health. A number of fruits and vegetables, including avocados and broccoli, have high amounts of soluble fiber that generate buyrate and other SCFAs. Without butyrate, bacteria become unstable and hyperactive, searching for ways to survive. Subsequently, the starved bacteria start a chain of unhealthy events. They attack the body’s cells, including the mucous layers of the colon and its epithelial lining, and the immune system goes into overdrive, causing chronic inflammation. If these conditions persist long enough in one’s gut, the healthy bacteria may disappear forever. “Younger and younger people are developing colon cancer sporadically, and we want to look at whether this may be related to a lack of butyrate in people’s diet,” Umar says. “We wanted to see if there was a way to replenish this crucial short-chain fatty acid in someone suffering from a gut disease like colitis.”

Using plant-based approaches, Umar and his lab are focusing on two products: pectin, a soluble fiber found in ripe fruit and jellies, and tributyrin, a triglyceride and insoluble fiber naturally present in butter. Pectin is not digested in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Instead pectin goes into the colon where bacteria aid in converting it to butyrate. In contrast Tributyrin, is not dependent on host bacteria to generate butyrate.

Germ-free (i.e., no bacteria) mouse models – meaning they lack short-chain fatty acid butyrate – received one of the two compounds. These mice therefore represent an excellent model system wherein to study the role of bacteria in colitis and colitis-associated colon cancer. “In these mice, pectin is never converted to that necessary butyrate,” Umar reports. “However, the tributyrin, because it does not require a microbiome to change to butyrate, protected the mice from developing colitis. Those mice seem to recover and appear less likely to develop colon cancer.”

Other efforts led by Umar include studying the direct relationship between the microbiome and intestinal stem cells in the gut, as well as a collaboration with Children’s Mercy studying necrotizing enterocolitis, a devastating disease that affects the intestine of premature infants, and how establishing a healthy microbiome early on influences their health. “I’ve always been fascinated by the world of microbes, and research increasingly shows that these play an integral role in our health,” Umar says. “The microbiome is the new frontier.”

Source: University of Kansas Cancer Center

11.03.2019