Biomarker validation

Plodding toward a pancreatic cancer screening test

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most deadly types of malignancies, with a 5-year survival rate after late diagnosis of only about 5%. The majority of patients—about 80%—receive their diagnosis too late for surgery. The disease spreads quickly and resists chemotherapy. In short, there is an urgent need for diagnostic tools to identify this cancer in its earliest stages.

“If we could detect the disease earlier, it could have a huge impact on survival for patients,” said Kenneth Yu, MD, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

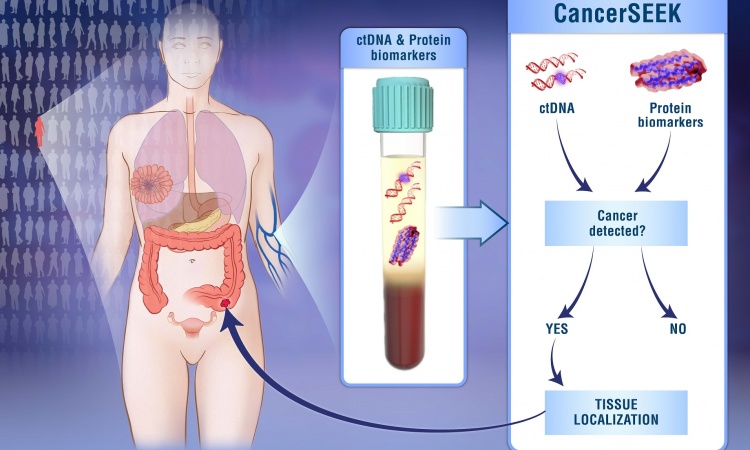

Despite decades of research, however, the only biomarker routinely used in pancreatic cancer testing is CA 19-9, a tumor marker helpful for monitoring disease progression but not sensitive or specific enough for screening. Over the past 10 years, the search for new biomarkers has intensified. Researchers have identified a variety of candidates for use in screening, from serum proteins to circulating tumor DNA to proteins on exosomes. Yet experts in the field say it’s too early to identify any particular biomarker or approach that is likely to reach clinical practice.

“The literature is full of promising candidate biomarkers, but I don’t know of any that have been validated across large platforms,” said Randy Haun, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences College of Pharmacy in Little Rock who has researched pancreatic cancer biomarkers. “It’s not that people aren’t trying. It’s a very tough problem.”

The Research Challenge

Ideally, a pancreatic cancer screening tool would be available to the general population because most cases arise sporadically, unrelated to known risk factors. That sets a high bar for test performance because the disease is rare, with only slightly less than 54,000 new diagnoses each year in the U.S. “To screen the general population for something like this, you need a test that’s extremely specific and sensitive,” Haun said. “It would almost have to have perfect 100 percent sensitivity and 100 percent specificity.”

The hunt for good biomarkers that meet these criteria is hindered by the relatively low number of patients and samples available for research. Finding the tens of thousands of subjects needed to conduct validation studies poses a major challenge. “Although the disease is headed to be a major cancer killer at number two by 2030, it’s still quite a rare disease,” said Eithne Costello, PhD, a reader in molecular and clinical cancer medicine at the University of Liverpool in the U.K. who researches pancreatic cancer biomarkers. “For any single hospital or laboratory, the number of samples they may have is very low.”

Making matters worse, of the few available samples, even fewer are from early-stage patients. “Most of the samples that have been used in the past have been from people with late-stage disease,” Costello said. “One of the problems with that is, even if you find markers that can distinguish those patients from healthy controls or disease controls, it’s not clear that the markers you’re looking for would detect the cancer earlier.”

Also, pancreatic cancer advances quickly, on average taking only 1 year for a tumor to grow from undetectable to inoperable, said Michael Goggins, MD, a professor of pathology and pancreatic cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. “That’s a hard window,” he said. In breast or colon cancer, when a small tumor or precancerous growth is detected it rarely has spread to other parts of the body. Precancerous changes in the pancreas are often microscopic, and by the time even a 2 cm tumor is discovered on the organ, it has usually already spread to lymph nodes.

Slow but Steady Progress

Scientists are working hard to overcome these challenges. Programs such as the Early Detection Research Network—an initiative of the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) National Cancer Institute—help institutions collaborate to amass enough samples for study. To address the lack of early-stage samples, a team of NIH-funded researchers began this spring to build a cohort of 10,000 adults who have new-onset diabetes (NoD), a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. About 1 in 125 members of the NoD cohort are likely to be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer within 3 years, allowing researchers to create a biobank of clinically annotated specimens. The hope is that many will be early-stage specimens. “That’s going to provide immense opportunity for researchers and scientists to either discover new biomarkers or to investigate promising candidates,” Costello said.

Meanwhile, efforts are underway to narrow the candidates for screening by better identifying at-risk populations. Goggins and his colleagues use a statistical analysis tool called PancPro to estimate risk based on family history and genetics, using data from the National Familial Pancreas Tumor Registry at Johns Hopkins. They then screen at-risk patients with endoscopic ultrasound and MRI to detect precancerous changes in cells. Goggins and his colleagues have not yet demonstrated improved survival rates, he said, but they have detected more early-stage cancers than would be expected without screening, and sometimes they are able to detect and treat precancerous cells. “We can’t say, but we might have cured them by intervening with an operation,” Goggins said.

Promising Biomarkers on the Horizon

While imaging still is the primary method for detecting pancreatic cancer, blood-based biomarkers could eventually play a role, possibly in panels or as adjuncts to imaging, and a variety of biomarker candidates have been identified so far.

Serum proteins are prime candidates because of the simplicity of testing blood samples, and many studies have applied mass spectrometry-based proteomics to search for tumor proteins in serum. Some have identified panels of proteins that distinguish pancreatic cancer patients from healthy individuals. “The problem with that approach is there are thousands of components in the blood,” Haun said. “It’s like searching for the needle in a haystack.”

Beyond proteins, researchers have looked for other biomarkers in blood. One study showed that elevated levels of branched-chain amino acids can be detected years before patients developed pancreatic cancer, perhaps a sign that early-stage cancer affects metabolism (Nature Medicine 2014;20:1193–8). “There’s a lot of interest in pursuing this idea of metabolic changes, whether it’s branched-chain amino acids or other changes in metabolic pathways,” Yu said.

Circulating cell-free nucleic acids are another area of intense research. Most pancreatic cancer patients have mutations of the KRAS gene, which can be detected by analyzing circulating tumor DNA found in blood. “But detecting a KRAS mutation by itself wouldn’t necessarily be completely beneficial because you can carry a KRAS mutation for 20 years before you might develop pancreatic cancer,” Haun said.

Another line of research looks at exosomes, which are vesicles released from cells. One study showed that a protein called glypican-1 on the surface of exosomes is detectable in blood and very sensitive and specific for pancreatic cancer (Nature 2015;523:177–182). Study co-author Raghu Kalluri, MD, PhD, professor and chair of the cancer department at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, said more papers on this biomarker, including a double-blinded study, will be published soon.

“At this point, based on the specific technique we reported, this is a viable marker and continues to look promising,” Kalluri said. “The issue is that the techniques to identify glypican-1-positive exosomes are complicated and may be hard to implement clinically unless easier and cheaper methods are explored in the near future.” In addition, Kalluri believes that a panel of biomarkers would be more useful than a single marker.

Researchers are also exploring protein and DNA biomarkers in pancreatic juice, miRNA markers, cytokines and chemokines, autoantibodies, circulating tumor cells, and even biomarkers in saliva. “I think there’s a lot of very good work being done, but most of the markers that [have been reported in the scientific literature] absolutely need to be validated in better cohorts,” Costello said.

While progress is slow, technology continues to advance and new potential biomarkers continue to be discovered, according to Haun. “It’s just a long, drawn-out process for something [for which] you really would want advances much more quickly because of the devastating nature of the disease,” he said. “There is good news out there, it’s just going to take awhile.”

Source: AACC/Julie Kirkwood

13.07.2017