Interview • Neurology

On-going malignant astrocytoma vaccine tests

A new vaccination for malignant astrocytoma brings such patients hope. However, research is still in its infancy.

Interview: Eva Britsch

We spoke with Professor Michael Platten, Medical Director of the Neurological Clinic at Medical University Mannheim, about the present state of research and the serious opportunities this presents. During the interview, he also revealed how cooperation with the pharmaceutical industry is developing and why the current results are only conditionally resilient. From July 2015 to July 2017 Professor Michael Platten and colleagues treated 33 patients with newly diagnosed malignant astrocytoma with a novel vaccine.

What is the current state of affairs?

‘We have completed the study and are in the follow-up phase. The patient data are currently evaluated. However, over the next few months we will collect and evaluate further data on the patients’ progress. At the same time, we are currently conducting intensive research on the patients’ blood samples to gain a better understanding of the immune reactions.’

Can definitive statements be made about the vaccination reducing the risk for astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma* patients to recur?

‘No. In addition to vaccination all patients received effective radiation and chemotherapy, which also prevents recurrent tumour growth, even if only for a limited period. Whether this recurrence risk is further reduced by vaccination can only be answered in a comparative study. We can start such a study once we have fully evaluated the current study.’

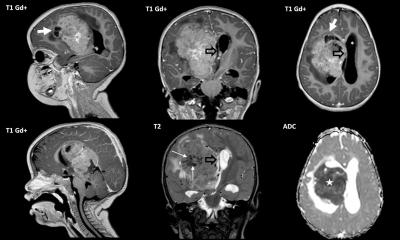

How does the new vaccination work and how can it be seen in combination with previously known treatment options?

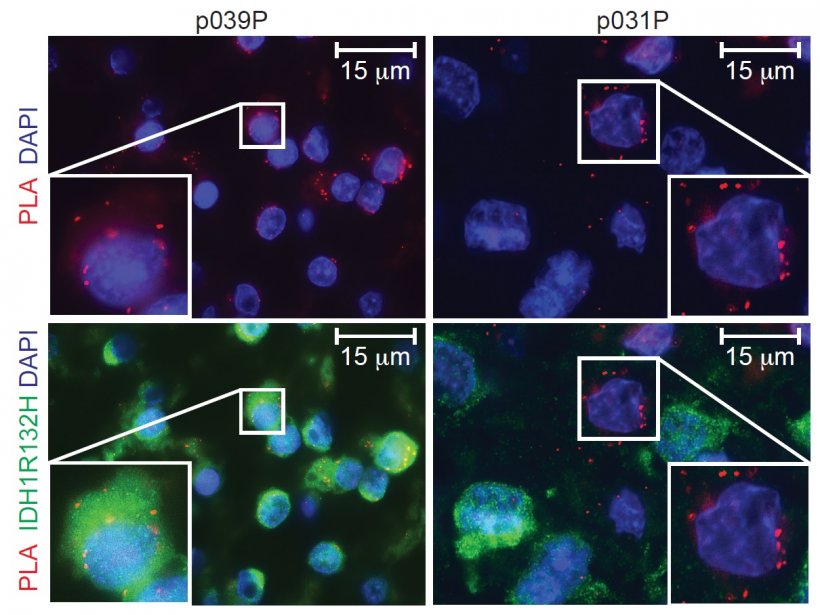

‘The vaccination is intended to sensitise the immune system of patients concerned to a protein molecule that is characteristically altered in the tumours of the patients, namely by the exchange of a single building block. We call this change IDH1R132H. With the vaccination we can sensitize the immune system so specifically that only the altered protein molecule in the tumour cells, IDH1R132H, but not the healthy form, IDH1wt, which can be found in all healthy body cells, is recognized. We hope that this specific sensitization of the immune system through vaccination will lead to the targeted treatment of tumours, as we have observed in animal experiments. We also assume that radiation therapy of the tumour, a proven therapy for these tumours, helps the sensitized immune system to fight the tumour.

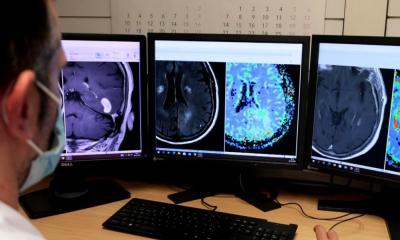

You and colleagues are currently evaluating the immune reactions of patients to the vaccine – how do you evaluate the reactions?

Very positive. The vast majority of patients develop specific antibodies against IDH1R132H as a result of vaccination, but also T-cells, two important components of the immune system. We are currently evaluating which factors influence the strength of the immune reactions and, of course, whether these have an influence on the further course, i.e. freedom from recurrence. We are also interested in finding out why individual patients have not experienced an adequate or delayed immune reaction.’

Does the vaccination have (previously known) risks?

‘The only relevant risks we have observed are vaccination reactions at the injection site with redness and itching. This reaction is to be expected and is mainly the result of the necessary vaccination booster.’

If we succeed in defining these specifically modified protein molecules for each individual patient and in developing a tailor-made vaccination therapy, then such a vaccination could in principle be used for all types of tumours

Michael Platten

Could a similar vaccine be developed for other cancers?

‘In rare cases IDH1R132H can also occur in other types of tumours, for example in bile duct carcinomas. In principle, all tumour types in which IDH1R132H is present are suitable for vaccination.

‘On a super-ordinate level, mutated protein molecules are found in practically all tumours, but they are usually patient-specific. If we succeed in defining these specifically modified protein molecules for each individual patient and in developing a tailor-made vaccination therapy, then such a vaccination could in principle be used for all types of tumours. However, this would then be a real individualised cancer immunotherapy that could not simply be taken out of the medicine cabinet.’

Could your research lead to new treatments for multiple sclerosis, which you are also researching?

‘We always try to learn from other diseases. For the current vaccination we use many findings and models, including multiple sclerosis, because an unwanted excessive immune reaction occurs in the brain there. If we understand the mechanisms that lead to this excessive immune response, then we can better control the immune responses in brain tumours.

‘Conversely, many of the breakthrough technologies we use to analyse immune responses in brain tumour patients can also contribute to a better understanding of multiple sclerosis.’

How does the pharmaceutical industry respond to your research?

‘Let’s say: with cautious interest. But, we have now begun a cooperation with the industry that combines our vaccination approach with an approved cancer immunotherapy drug. Through this intelligent combination, we hope to make our vaccination therapy even more effective. This clinical trial will start in the next few weeks.’

What hampers your work?

‘Financing is certainly a major obstacle; so far we have financed all studies from public subsidies. The German Cancer Research Centre, the National Centre for Tumour Disease, German Cancer Aid and the Federal Ministry of Education and Research have given us considerable support, for which we are very grateful. Without this support, implementation would not have been possible.

‘We are also very grateful for the good cooperation with the Paul Ehrlich Institute, which actively supports us in these innovative therapeutic approaches.’

Could patients hope to receive vaccination beyond their research status?

‘It’s probably too early for now. We are currently focusing all our efforts on the follow-up study. Until we can say for sure whether the vaccination therapy will actually work and, if so, in which patients and under what conditions, research in the form of clinical studies will be a priority. However, we are very pleased that the patients affected and their relatives are supporting us by participating in the studies.’

* A rare, slow-growing tumour that begins in oligodendrocytes – the cells covering and protecting nerve cells in brain and spinal cord.

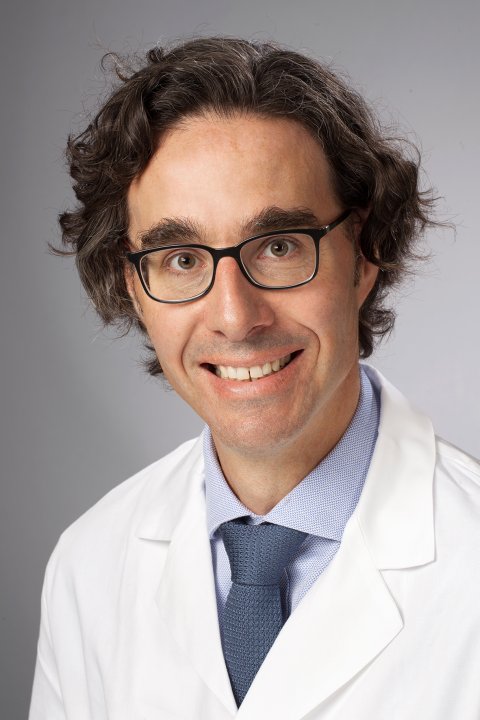

Profile:

Michael Platten MD is Medical Director of the Manheim Medical University Neurological Clinic and professor of clinical neurology, neuroimmunology and neuro-oncology at Heidelberg University. In recent years he has also led brain tumour immunology at the German Cancer Research Centre (DKFZ) in Heidelberg, Germany.

10.05.2019