Image source: Shutterstock/crystal light

Article • WSI, AI and more

New digital frontiers for nephrology

Digital technology solutions are creating new opportunities for pathologists in diagnosis and assessment of renal conditions.

Report: Mark Nicholls

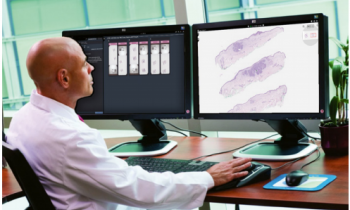

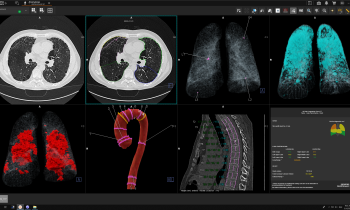

With the opportunity for whole slide imaging (WSI), improved workflow and better visualization, hospitals and laboratories are already seeing a return on the investment in such technology. Artificial Intelligence is also offering a new dimension and forging new frontiers in nephrology and, whilst it may still have limitations, clinicians are starting to understand and recognise the potential AI offers.

Advantages and hurdles

By 2020, all our pathologists were using digital pathology as their most important diagnostic tool

Pablo Cannata

The challenges laboratories and hospital systems face in adopting digital solutions for nephrology were outlined during the ‘Nephrology; New frontiers – nephrology goes digital’ session during the online 33rd European Congress of Pathology. Delegates also heard about advantages and benefits detailed by five expert speakers.

Dr Pablo Cannata from the Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz (FJD) in Madrid, Spain, described advantages and hurdles of going digital, reflecting on the experience of the FJD pathology department, which introduced digital pathology in 2018 for renal pathology and uropathology. Within a year, almost all slides – except for cytopathology – were scanned digitally, though he acknowledged that some pathologists were initially reluctant to use digital pathology as the only solution for diagnosis. ‘Some were still using microscopes,’ he explained. ‘But, by 2020, all our pathologists were using digital pathology as their most important diagnostic tool.’

Workflow improvements

Cannata explained that the main university hospital works as a refence hospital for three other hospitals from the group, with all the slides from the various scanners uploaded to the same cloud.

Other hurdles in the transition to digital pathology, he said, were the high initial cost, revision of the pre-analytical phase, and integration with the Laboratory Information System (LIS). However, he said, ‘There have been clear and wide-ranging advantages from going digital. These are the ability to offer telepathology in small pathology labs where there is no renal pathologist, it has delivered improvements in workflow, and supported annotation and quantification of pathologic findings.’ It also allows better and faster visualisation of serial sections, enables a global vision at different levels for more accurate diagnosis, and ‘opens the door for computational pathology.’

Global application

Dr Vijaya B Kolachalama, Assistant Professor in the Department of Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine and the Department of Computer Science at Boston University, highlighted various aspects related to the role of AI in pathology. Machine learning, he said, can perform various tasks, such as diagnosis and staging of disease, biomedical segmentation, prognosis, and biomarker development (omics and drug discovery).

However, Kolachalama added, there are limitations to its global application, which depend on the location. ‘For developed countries, or places with good clinical resources, the argument is that AI can assist the pathologist. ‘For developing countries, or for places with limited clinical resources, the argument is that AI can serve as a tool to perform diagnosis/screening of patients. ‘The sobering reality is that none of these tools are fully deployed in clinical settings. Tools are still largely under development.’

The reality gap

The ‘exciting aspect’: the field is open for researchers and entrepreneurs to build these technologies, and there is huge potential for telepathology. Kolachalama said more publicly available kidney pathology datasets are needed that are representative of clinical practices globally to accelerate research in computational pathology. He also underlined the importance of validation of computational algorithms to ensure that models developed on a single cohort of data are generalisable across other populations. There also remains a gap between reality and hype surrounding explainable AI, and questions remain over demonstrating clinical and workflow benefits and who is going to pay for these AI-driven systems.

The session also covered having a Central Repository for Digital Pathology, which was discussed in a presentation by Renate Kain from the Department of Pathology at the Medical University of Vienna; Dr Peter Boor, from the Pathology and Nephrology Department at RWTH Aachen in Germany, looked at pathomics as a novel tool for mining histology data; and Dr Romain Bulow, from the same unit, looked at deep learning-based classification of kidney allograft pathology.

Profile:

Dr Vijaya B. Kolachalama, Assistant Professor in the Department of Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine and of the Department of Computer Sciences at Boston University and a founding member of the faculty of computing and data science at Boston University. His research group focuses on developing deep learning algorithms for disease risk assessment, as well as biomarker development and software design to assist therapeutic development and clinical decision-making.

17.11.2021