Infectious diseases

New biospleen blood cleansing excites experts

A new extracorporeal nanotech device addresses the root cause of sepsis by removing pathogens and endotoxins simultaneously from blood even before their identification – this genetically engineered mannose-binding lectin protein can also latch on to the Ebola virus...

Report: Cynthia E Keen

Sepsis is on the rise worldwide, in all likelihood exceeding the 2003-2013 estimates of 18 million cases. 30-50% of patients die, whether treated in a high-tech intensive care unit (ICU) or a resource-constrained hospital ward. In developing countries, sepsis causes 60-80% of all deaths (source: Global Sepsis Alliance). It also kills around six million infants and young children and 100,000 new mothers annually.

No specific anti-sepsis drugs are commercially available. Thus the presentation from Harvard University’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering in Boston of a dialysis-like blood cleansing biospleen device that can filter live and dead pathogens from human blood, generated tremendous excitement at the 6th Annual Molecular Diagnostics for Infectious Disease conference held in Washington, D.C. in late August*.

Inspired by the spleen, the extracorporeal blood-cleansing device is revolutionary in its ability to continuously remove pathogens and toxins from blood without first identifying the infectious agent. Time is vital – sepsis mortality rates increase as much as 9% for every hour before a correct antibiotic therapy is administered – the device offers the potential to rapidly treat systemic blood infections and prevent sepsis progression.

‘The biospleen device addresses the root cause of sepsis by removing pathogens and endotoxins simultaneously,’ principal investigator Michael Super PhD, Senior Staff Scientist, told European Hospital. ‘Blood pathogen load is known to be a major contributor to both disease severity and mortality in patients with sepsis. Many patients respond to appropriately targeted antibiotic therapies that work exclusively by lowering the number of live pathogens, but antibiotic therapy does not treat endotoxins in a patient’s blood. Therefore, we set out to develop an extracorporeal blood-cleansing therapy, similar to dialysis, that can rapidly remove microorganisms and endotoxins from the blood without the need to first identify the source of the infection and without altering blood contents – and it has exceeded our expectations, by being able to filter these out in a matter of hours.’

Magnetic micro-bead magic

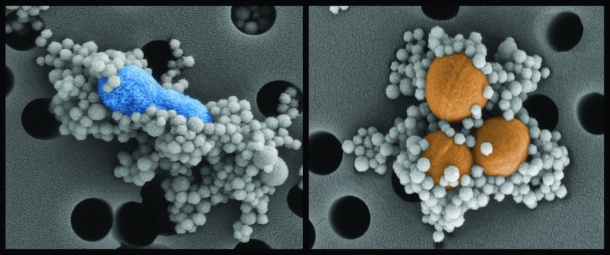

The biospleen unit uses magnetic nanobeads coated with a genetically engineered human opsonin – mannose-binding lectin (MBL) that binds to a wide variety of pathogens. In its innate state, MBL has a branch-like ‘head’ and a stick-like ‘tail’. In the body, the head binds to specific sugars on the surfaces of all types of bacteria, fungi, viruses, protozoa and toxins. The tail cues the immune system to destroy them. ‘The protein is part of the innate immune system that has been binding sugars for 500 million years. It’s a very robust pathogen capture mechanism,’ he explained.

Because other immune system proteins can bind to the MBL tail and activate clotting and organ damage, Dr Super used genetic engineering tools to remove the tail and graft on a similar one from an antibody protein that does not cause these problems. This genetically engineered ‘secret sauce’ protein binds the pattern of sugar on the surface of the pathogens – more than 100 different species, but does not bind to mammalian host cells.

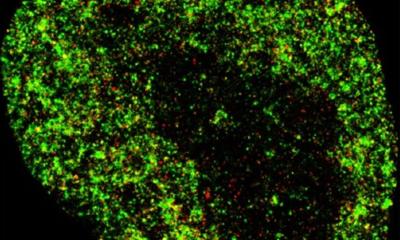

Dr Super described how the engineered MBL ‘secret sauce’ protein is attached to magnetic beads 128 nanometers in diameter. The beads are added to blood removed from the patient and bind to the pathogen. Magnets in the biospleen device pull the now pathogen-coated magnetic beads through the channels to cleanse the blood, which is then returned to the patient.

Dr Super and his colleagues tested the device on anaesthetised laboratory rats infected with bloodstream infections that human sepsis patients experience. Approximately 90% of live S.aureus and E. coli pathogens were removed within 60 minutes. Rats were challenged with lethal doses of endotoxin and 90% of the biospleen-treated rats survived, while only 14% of the control rats survived.

Tests of human blood in vitro removed more than ninety percent of key sepsis pathogens when the blood flowed through a single device at a rate of half to one litre per hour.

Dr Super advised that many devices could be linked together to obtain levels required for human blood cleansing at dialysis-like rates. Alternatively, a patient could undergo multiple rounds of the cleansing treatment.

The next step is to test the device on large laboratory animals, starting with pigs. He anticipates that initial human clinical trials would be carried out with patients in ICUs with severe sepsis. Patients with earlier-stage disease would likely require confirmation of septicaemia before starting the biospleen.

The device also might be able to reduce the spread of infectious agents to organs and additionally might lower levels of circulating endotoxin and inflammatory cytokines. It also may be the only option to fight sepsis caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

‘One of the huge advantages this device offers is that it is not necessary to perform a culture. Septic patients need treatment immediately. An accurate pathogen diagnosis takes one day to a week. Culture followed by antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) takes two to seven days. Today, doctors are forced to make a decision on how to treat a patient without ever getting the lab data. We are working to change that paradigm,’ Dr Super said.

Dr Super added: ‘We see this technology being used as a ‘front-end’ technology for pathogen collection and concentration before doing molecular diagnostic tests such as Mass-Spectrometry, PCR and Next Generation Sequencing (NGS). The pathogen capture can be used to ‘clean up’ the sample, removing human proteins and DNA that interfere with molecular diagnostic tests. ‘For example, when human DNA contaminates a bacterial DNA sample, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for bacterial DNA will not work reliably. We are focusing on how to clean up the sample so that we can do PCR.’

He anticipates that the biospleen device will be a platform technology with the ability to remove proteins like cytokines or autoantibodies as well as other types of cells, e.g. cancer cells from the whole blood volume of patients by coating the magnetic beads with appropriate cell- or protein-specific ligands.

Could such a device help curtail a future Ebola-like epidemic? The team confirms that the ‘secret sauce’ MBL protein does bind to Ebola. Dr Super did not know if a dialysis-like technology would work in view of the scale of the disease. ‘But we could imagine having this technology available as a safety net for medical staff treating Ebola patients.

‘What is so powerful about this technology is the ability to remove pathogens from a person’s blood even before having the time to identify it.’

* See 14/9/2016 article in Nature Magazine online: (www.nature.com/nm/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nm.3640.html)

27.11.2014