Article • Cardiology & the sexes

Why heart attacks are different for women

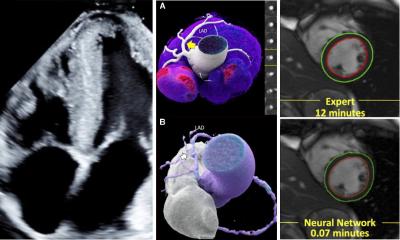

MRI has a central role in picking up myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary disease, a condition that particularly affects women but is often left untreated, with potentially fatal outcome.

Report: Mélisande Rouger

Heart attack in women presents differently than in men and requires a different approach when it comes to detection and prevention, according to Allison Hays, a cardiologist and assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, speaking at CMR 2018 meeting in Barcelona. ‘Women don’t present typically with chest pain, but rather with tiredness or shortness of breath. When they eventually come in for diagnosis, women have much less rates of having abnormal cardiac catheterisation test, which shows degree of stenosis in coronary arteries. So, much more commonly, they do not have disease in the coronary arteries,’ Hays explained. Instead, women who suffer a heart attack usually present with myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary disease (MINOCA), a much less common condition in men. This difference suggests that biology of the coronary arteries differs greatly between sexes. Women have a much higher incidence of microvascular diseases, i.e. the very small vessels that are embedded into the heart muscle itself.

Women are now more represented and more involved

Allison Hays

Treatment usually includes lifestyle modifications and traditional ways to lower risk factors such as blood pressure and high cholesterol. Nonetheless, heart attack has a worse prognosis in women than men, because it is generally not treated as aggressively as it should be, Hays argued. ‘A lot of women don’t have complete heart blockages and sometimes they’re left untreated. So it’s very important to recognise that even when a woman comes in with a heart attack and they don’t have heart blockages that are detected on cardiac cath, it’s very important that you still treat them for the small vessels disease aggressively with heart medication,’ Hays said.

A main focus of CMR 2018 was to highlight the different and atypical presentation of women compared to men when it comes to heart attacks and how they can be detected, prevented and addressed in women, to improve outcome in the future. Although cardiac arrest is the first cause of death in women as well, it was the first time the conference featured a dedicated session on the topic, probably because women are now better represented in the organising societies, Hay believes. ‘In the last two years of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, membership of women has grown significantly, going up from 20% to 40% today. So women are now more represented and more involved. I myself was one of the organisers, and found it was important to talk about that issue. The session was well attended, and we’ve had very good questions from the audience. I think this topic should be there every single year, because there’s a lot of research in that area,’ she said.

Recommended article

News • Gender issues

Clinical trial enrolment favours men

Clinical trial enrolment favours men, according to a study presented at Heart Failure 2018 and the World Congress on Acute Heart Failure, a European Society of Cardiology congress.1 The study found that fewer women meet eligibility criteria for trials of heart failure medication. Helena Norberg, author of the study, junior lecturer and PhD student, Umeå University, Sweden, said: “One of the…

MRI plays a critical role not only for microvasculature disease, but also for heart failure, since a lot of women have heart failure with preserved injection fraction

Allison Hays

Awareness of that issue among the medical field must be increased, and the approach in detection must change, particularly regarding stress perfusion MRI, because this is an ideal tool to image heart disease in women, Hays believes. ‘Some stress tests are better tailored to women because they are more sensitive. Stress MRI is particularly suited to heart attack detection in women because it’s better at imaging microvasculature. ECG is not so sensitive for women and you can miss a lot. The same is true for CT, because you’re just taking pictures to know how much narrowing or blockage there is, but it does not capture how much small vessel disease you have. Both modalities miss a lot of disease in women,’ she pointed out.

The novel field of non-contrast MRI, which uses T1 and T2 mapping, may be an additional tool to detect areas of microvasculature perfusion in women. The technique has a lot of prospects but it is still a very new area of research and requires more investigation, Hays underlined.

In the USA the Women's HARP study, a multi-centre, diagnostic observational study that aims to compare perfusion MRI results of women with heart attack to cardiac catheterisation techniques using optical coherent tomography will bring more knowledge of MRI’s value within the next two years. It will also provide information on plaque inflammation and see whether this correlates with microvascular abnormalities. ‘That will be interesting, to determine the reasons why there is microvascular dysfunction,’ Hays said.

MRI is usually less available than other modalities, but it is worth the extra effort to find centres of excellence because of the unique insights it offers, and not just in microvasculature, she believes. ‘CT and nuclear tests are not so sensitive to image microvasculature. MRI plays a critical role not only for microvasculature disease, but also for heart failure, since a lot of women have heart failure with preserved injection fraction.’

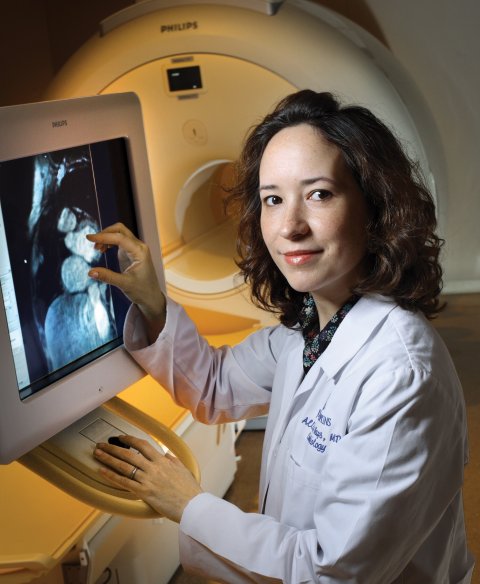

Profile:

Allison Hays MD is a general cardiologist and interim Director of Echocardiography Programs at the Johns Hopkins Heart and Vascular Institute. She is also an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Having graduated from Stanford University she received medical training at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Following her residency at the New York Presbyterian Hospital at Columbia Hays pursued cardiology fellowships at New York University Medical Center and at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Today she studies ways to use non-invasive imaging to detect cardiovascular disease. In terms of research, Hays uses cardiac MRI as a tool to study coronary and systemic endothelial function.

26.08.2018