News • Neural development

Why our brains fold the way they do

Everyone knows what our brains look like – but why is it folded up like that? Looking at other species reveals much less folding or even none at all. Scientists in Dresden, Germany, have now taken a closer look at the ridges and grooves of human brains. They discovered what causes our brains to fold – and what happens when the folding process goes wrong.

Source: Pixabay/geralt

Our study provides a missing link between prior genetic and biophysical studies

Wieland Huttner

During human evolution, the size of the brain increased, especially in a particular part of the brain called the neocortex. The neocortex is responsible for our higher cognitive functions like speaking or thinking. To enable its expansion, the brain forms folds during fetal development that allow fitting the enlarged neocortex into the restricted space of the skull. The right amount and position of folds during the development of a fetus is crucial for proper brain function. If the folding process is disrupted, as is the case in a developmental disorder called lissencephaly ("smooth brain"), this can result in cognitive defects. Until now, researchers knew very little about which molecules drive the folding of the human brain, and how. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG) in Dresden, in collaboration with colleagues at the Leibniz Institute of Polymer Research Dresden (IPF) and the University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus Dresden (UKD), now identified a novel extracellular matrix-driven mechanism that is essential for human neocortex folding. The researchers published their findings in the journal Neuron.

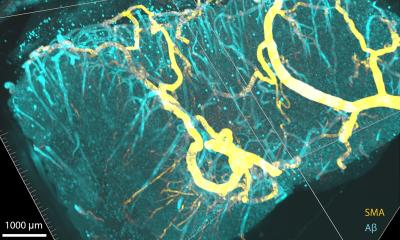

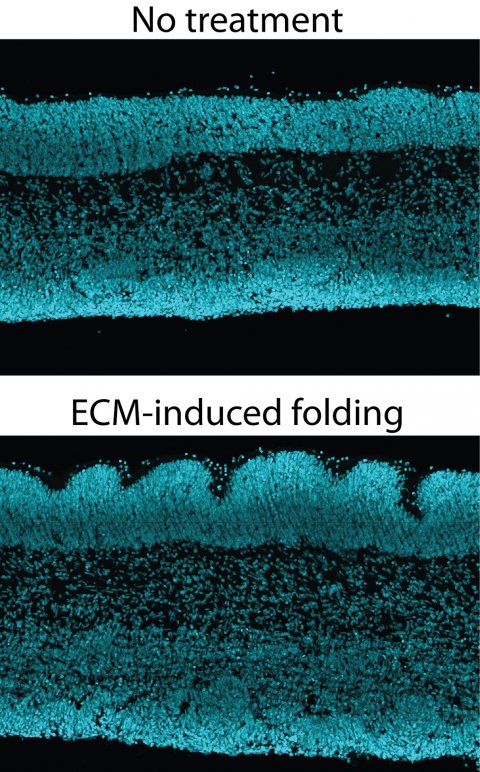

The neocortex is the seat of many of the higher cognitive functions that are unique to humans, such as our speech or the ability to learn. This part of the brain has expanded greatly in human evolution, and a key aspect of this expansion is the folding of the cortical surface. It is therefore crucial to gain a better understanding of how the human brain folds. To investigate this, researchers at the MPI-CBG, in collaboration with colleagues at the IPF and UKD, examined the potential role of the extracellular matrix in the formation of brain folds. The extracellular matrix, a non-cellular three-dimensional macromolecular network, has been previously associated with the expansion of the neocortex. The researchers focused on three proteins in the extracellular matrix: hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1 (HAPLN1), lumican and collagen I. Dr. Katherine Long, the lead author of the study, explains: “When we added these three proteins to tissue cultures of fetal human neocortex, the cortical surface started to fold. This folding was linked to an increase in hyaluronic acid, which turned out to be essential for folding.” Further experiments showed: When hyaluronic acid was reduced in the tissue, the effect of the three proteins on the folding process was blocked, and the folding was either stopped or even reversed.

Prof. Wieland Huttner, who supervised the study, summarizes: “Our study provides a missing link between prior genetic and biophysical studies. We present a new model system to study folding of human neocortex tissue. This system also provides insight into disorders of human brain development.”

Source: Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG)

05.08.2018