Understanding breast cancer functions

Mark Nicholls reports

High resolution radionuclide imaging is a technique increasingly used to detect breast cancers and has already been shown to offer improved diagnosis in many clinical situations. The technique, which will be discussed at RSNA 2010 (28 November to 3 December, Chicago) , is also allowing clinicians to detect previously unknown areas of breast cancer in women with newly-diagnosed disease.

Professor Rachel Brem, Director of the Breast Imaging and Interventional Centre and Professor of Radiology at George Washington University, Washington DC, has been involved in the development of the high resolution radionuclide imaging technique since its inception in the mid 1990s. On 28 November, at this year’s RSNA meeting, she will lead a session on high resolution radionuclide breast imaging.

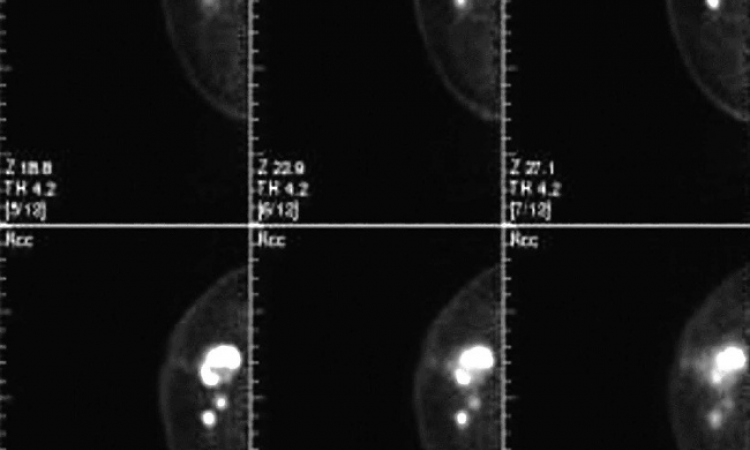

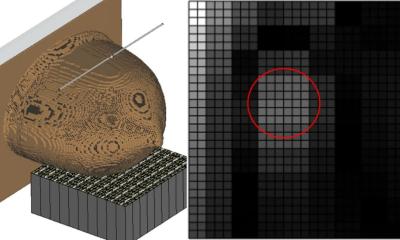

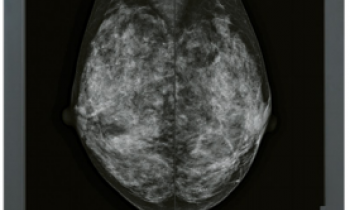

Prof. Brem explained that high resolution nuclear medicine imaging of the breast is a functional approach to breast cancer diagnosis. ‘This uses a high resolution, breast specific gamma imaging that allows for the detection of both invasive and non-invasive breast cancer as small as 1mm. We can reliably detect 2mm cancers with this approach.’ The approach of breast specific gamma imaging (BSGI) is that unlike mammography and ultrasound - which is based on anatomy and asks the question what does breast cancer look like - BSGI asks the question how does breast cancer function differently to the normal surrounding breast tissue. ‘This allows us to use a fundamentally different approach to improve breast cancer detection. The imaging can also be a comfortable experience for the patient, who can sit and read or watch a video during the process and is of particular benefit to women who cannot undergo an MRI scan.’

High resolution radionuclide imaging has a number of advantages in the diagnosis and detection of breast cancer. Professor Brem, who is also Vice-Chair, Research and Faculty Development, at George Washington University, explained: ‘It is used in surveillance of high risk women, in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer for surgical planning as well as for detection of occult foci of breast cancer.

Ten per cent of women with newly diagnosed breast cancer have another focus of cancer that would not have been detected without BSGI. It has at least equal sensitivity and better specificity than MRI and can be used in all women who have venous access. Therefore, women who cannot undergo MRI can undergo BSGI with at least equal sensitivity and better specificity.’

During the RSNA session Professor Brem will review the BSGI literature, discussing clinical uses and demonstrating clinical situations where BSGI is used, and the newly-approved direct gamma biopsy device as well as looking at comparison to breast PET or PEM and future developments regarding BSGI.

Use of the technique is growing, several hundred units are in use and over half a million women have been imaged, she said. The technique is in daily use in Professor Brem’s practice and, in practices that have BSGI, it has become an integral part of their breast centre. The number of centres with BSGI continues to grow, both in the USA and elsewhere.

And there are clear benefits of BSGI for the clinician and also for the patient. ‘It results in improved diagnosis of breast cancer in many clinical situations. It allows us to detect additional, previous unknown areas of breast cancer in women with newly-diagnosed disease and it’s a powerful and novel addition to our armamentarium of approaches to optimal breast cancer detection,’ she pointed out. ‘For the patient, it offers improved breast cancer detection using a physiologic approach with better specificity than MRI.’

Work continues in developing the technique, with ongoing studies targeted at lowering the ‘already low and acceptable dose’ of radiotracer used, as well as further integration of BSGI with other imaging modalities.

28.10.2010