Seeking the genetic basis of diabetes

Mark Nicholls reports

Researchers have identified 12 new genes associated with Type 2 diabetes (T2D) that look set to improve the understanding of the processes underpinning the condition. The findings could also offer new biological pathways that can be explored as targets for new therapies to tackle T2D.

The new genes were identified by a consortium of scientists led by Professor Mark McCarthy, of the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics at Oxford University, in the largest study so far of the connections between differences in people’s DNA and their risk of diabetes.

Prof. McCarthy said: ‘The signals we have identified provide important clues to the biological basis of T2D. The challenge will be to turn these genetic findings into better ways of treating and preventing the condition.’

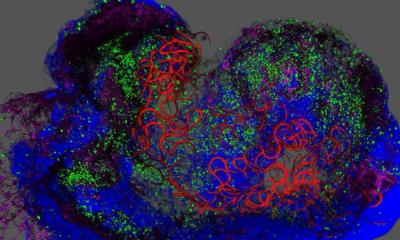

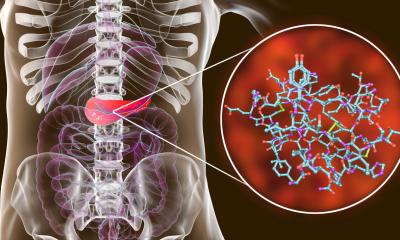

The identification of 12 new genes brings the total number of genetic regions known to be associated with T2D to 38. The genes tend to be involved in the working of pancreatic cells that produce the hormone insulin, the control of insulin’s action in the body, and in cell-cycle regulation.

Prof. McCarthy said it was a significant theme to the research that several of the genes seemed to be important in controlling the number of pancreatic beta-cells and added: ‘This helps settle a long-standing controversy about the role of beta-cell numbers in T2D risk and points to the importance of developing therapies that are able to preserve or restore depleted numbers of beta-cells.’

To arrive at their findings, the researchers (from the UK, Europe, USA and Canada) compared the DNA of over 8,000 people with T2D with almost 40,000 people without the condition at almost 2.5 million locations across the genome. They then checked the genetic variations they found in another group including over 34,000 people with diabetes and almost 60,000 controls.

Although the study found 12 new genetic regions where the presence of a particular variation in DNA sequence leads to an increased susceptibility to T2D, the individual effects are small.

The scientists say that possessing one of these gene variants leads to only a marginal, but clear, increase in the risk of developing the condition.

But the key, say researchers, is that the potential impact of the findings in terms of new biology and possible therapeutic developments could be significant. ‘Gradually we are piecing together clues about why some people get diabetes and others don't, with the potential for developing better treatments and preventing the onset of diabetes in the future,’ said Prof. McCarthy.

Dr Jim Wilson, Royal Society University Research Fellow at the University of Edinburgh and a member of the research team, said that a ‘very interesting finding’ of the research was that the diabetes susceptibility genes also contained variants that increased the risk of unrelated diseases, including skin and prostate cancer, coronary heart disease and high cholesterol. ‘This implies that different regulation of these genes can lead to many different diseases.’

The researchers now plan to use the availability of new tools for sequencing the whole human genome to explore further sources of DNA sequence variation that have been missed in previous efforts, in an effort to pin down the remaining genetic basis for T2D.

07.09.2010