© University of Notre Dame

News • Women's health

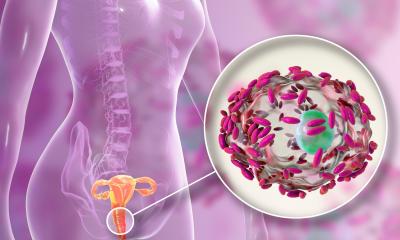

Why obesity makes ovarian cancer more deadly

A new study led by researchers from the University of Notre Dame links a high body mass index (BMI) to alterations in the structure and environment of cancerous tumors.

Most women with ovarian cancer are diagnosed with the most advanced form of the disease. Less than a third of those diagnosed with the disease survive five years later. As the third most common type of gynecological cancer, it led to more than 200,000 reported deaths globally in 2020 alone, according to a recent study. In a study published this month in the Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research, University of Notre Dame researchers in collaboration with NeoGenomics Laboratories have shed new light on one key factor that can make ovarian cancer especially deadly: obesity.

Obesity, considered a non-infectious pandemic, is known to increase the risk of ovarian cancer and decrease the likelihood of surviving the disease. A team of researchers led by M. Sharon Stack, the Ann F. Dunne and Elizabeth Riley Director of Notre Dame’s Harper Cancer Research Institute, and Anna Juncker-Jensen, senior scientist and director of scientific affairs at NeoGenomics, wanted to understand why obesity makes ovarian cancer more deadly.

The researchers analyzed cancer tumor tissues from ovarian cancer patients. They were able to compare the tissues of patients with a high body mass index (BMI) to those with a lower BMI, and two important differences stood out. In cancer patients with a BMI higher than 30 (the range for obesity determined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), the researchers found a particular pattern in the type of immune cells surrounding cancerous tumors. They found a change in the populations of a type of immune cells, called macrophages, infiltrating the tumor that are typically associated with more advanced cancer stages and poor survival. The cancerous tumors in obese patients were also surrounded in more stiff, fibrous tissue known to help tumors resist treatment by chemotherapy. The team was also able to confirm their findings by observing similar patterns in ovarian cancer-bearing mice fed a high-fat diet.

© University of Notre Dame; photo by Barbara Johnston

Stack, who also serves as the Kleiderer-Pezold Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry in the College of Science at Notre Dame, emphasized that the study offers hope for better treatments as the prevalence of obesity increases worldwide. “Our data give a more detailed picture of how and why obesity may affect ovarian tumor progression and therapeutic responses to the cancer,” Stack said. “We are hopeful that these findings will lead to new strategies for targeted therapies that can improve outcomes for ovarian cancer patients.”

This study was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Aging, the American Institute for Cancer Research, the American Cancer Society and the Leo and Ann Albert Charitable Trust.

Source: University of Notre Dame

22.07.2023