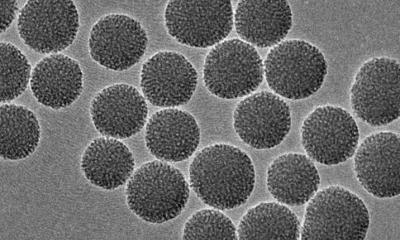

Nanospheres deliver high chemotherapy doses

Scientists have designed nanoparticles that release drugs in the presence of a class of proteins that enable cancers to metastasize. That is, they have engineered a drug delivery system so that the very enzymes that make cancers dangerous could instead guide their destruction.

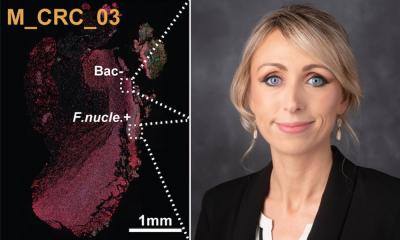

“We can start with a small molecule and build that into a nanoscale carrier that can seek out a tumor and deliver a payload of drug,” said Cassandra Callmann, a graduate student in chemistry and biochemistry at the University of California, San Diego.

The system takes advantage of a class enzymes called matrix metalloproteinases that many cancers make in abundance. MMPs chew through membranes, allowing cancer cells to escape to colonize other regions of the body, often with deadly consequences. Callmann created tiny spheres packed with the anti-cancer drug paclitaxel (also known by the trade names Taxol and Onxal) and coated with a peptide shell. MMPs tear up that shell, releasing the drug. The shell fragments form a ragged mesh that holds the drug molecules near the tumor.

The work, led by Nathan Gianneschi a professor of chemistry and biochemisty at UC San Diego, builds on his group’s earlier sucess using a similar strategy to mark tumors for both diagnosis and precise surgical removal.

To package the drug into the spheres, Callmann had to add chemical handles. As it turns out, a group of atoms essential to the drug molecule’s effectiveness, and also toxicity, made for a good attachment point. That means the drug was inactivated as it flowed through the circulatory system until it reached the tumor.

The protection allowed the researchers to safely give a dose 16 times higher than they could with the formulation now used in cancer clinics, in a test in mice with grafted in fibrosarcoma tumors.

In additional preliminary tests, Callmann and colleagues were able to halt the growth of the tumors for a least two weeks, using a single lower dose of the drug. In mice treated with the nanoparticles coated with peptides that are impervious to MMPs or given saline, the tumors grew to lethal sizes within that time.

Gianneschi says they will broaden their approach to create delivery systems for other diagnostic and therapeutic molecules. “This kind of platform is not specific to paclitaxel. We’ll test this in other models - with other classes of drug and in mice with a cancer that mimics metastatic breast cancer, for example.” They’ll also continue to modify the shell, to provide even greater protection and avoid uptake by organs such as liver, spleen and kidneys, he said. “We want to open up this therapeutic window.”

Source: UC San Diego

12.08.2015