© mikumistock – stock.adobe.com

Article • Hospitalists explore diagnostic and therapeutic adjustments

Dual challenge: Managing critical care of the pregnant inpatient

Hospitalists face a dual challenge when a critically ill pregnant patient is admitted to a hospital: providing safe and effective treatment for both mother and fetus. Pregnancy causes physiologic changes as well as anatomical ones, which complicates the assessment and medical management of pregnant women. At the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) in Las Vegas, an expert discussed why hospitalists must draw on a variety of skills when treating pregnant inpatients.

Special report: Cynthia E. Keen

Pregnancy causes physiologic changes as well as anatomical ones, which complicates the assessment and medical management of pregnant women. Hospitalists must play a critical role verifying the accuracy of clinical information, such as the comprehensiveness of patient-provided drug lists, analyzing the possible impact on pregnancy of lifestyle and pre-existing conditions, and answering questions posed by patient and family that are both general and fetal risk-related. They also need to be knowledgeable about how physiologic changes impact laboratory results and prescription medications.

Speaking at SHM Converge, Courtney Bilodeau, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine and Clinical Educator in Obstetric Medicine and Breastfeeding Medicine at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, stated that essential qualities include:

- Clinical expertise and knowledge

- Diagnosing and treating a wide range of medical conditions

- Staying updated on current medical advancements

- Problem-solving and critical thinking

- Strong interpersonal communication and teamwork skills; and

- Empathy and compassion.

Considering that this is the 21st century, the maternal death rate in the United States is shocking, she remarked. The National Vital Statistics System recorded 18.6 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2023.1 This is an improvement from 2020, when 23.8 deaths occurred, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). By comparison for that year, the most recent for comparative multinational statistics, the next highest rate in comparable European industrialised countries were much lower, with the highest being France, at 8.7 deaths.2 Factors in US mortality range from pre-existing conditions (e.g., obesity, hypertension), and unhealthy lifestyle (e.g., alcohol, smoking, illegal drug use), to pregnancy and birth related complications, including pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, peripartum hemorrhage, and venous thromboembolism (VTE).

2017-2019 CDC data reveal that 66% of pregnancy-related deaths occur in the postpartum period: 22% during pregnancy, 13% on the day of delivery, 12% one-to-six days postpartum, and 30% from 43 to 365 days. In many countries, including the US, there is a shortage of primary care physicians to provide after-birth medical treatment.3

Considering extensive changes

Because fetal well-being depends upon maternal well-being, the pregnant body works harder to meet the needs of the developing fetoplacental unit. Hospitalists must consider the normal physiologic changes in pregnancy and determine if changes in the patient are pathologic. 'It’s important to think what a diagnosis might be if a patient was not pregnant,' she said. 'Then consider how pregnancy physiology impacts these disorders.'

Pulmonary changes include the increase in the angles of a rib, changes in arterial blood gas measurements, lower esophageal sphincter tone, increases in upper airway edema, increased Mallampati score which predicts ease of intubation, increased risk for aspiration, decreased gastric emptying, and increased intra-abdominal pressure.

Kidneys hyper-filter during pregnancy. Renal blood flow increases by 50%. Creatinine clearance increases to levels of 120-160 ml/min, and levels of serum creatinine are decreased to 0.4 to 0.7 mg/dl.

Recommended article

News • Striking structural reorganisation

Pregnancy and nursing massively changes up mothers' intestines

When women are pregnant and nurse their babies, their bodies change to ensure the health of both mother and child. Researchers now surprisingly find that the intestine also changes completely.

Changes in the cardiovascular system include an up to 30% to 50% increase in cardiac output, potentially worsening pre-existing cardiac comorbidities. Compression of the aorta can result in hypotension. Total blood volume increases by 25% to 40%, and plasma volume by 40% to 50%. Pregnant patients are at greater risk of coagulation, causing anaemia. Elevation of the diaphragm and uterus enlargement contributes to the risk of hypoxia. All pregnant patients also become insulin resistant.

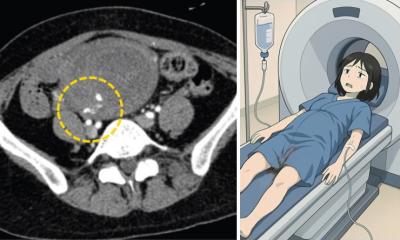

'Hospitalists need to consider what tests and imaging exams they order for a non-pregnant patient,' Dr Bilodeau advised. 'Can these diagnostic investigations be done safely in pregnancy, or is there another way by which to obtain the information needed? Are the lab tests changed by physiologic changes? Assess the risk of either not doing the work-up or delaying it until after delivery.'

Advice on radiation and medication

Although radiation dose exposure to the fetus should be avoided, if possible, there is no clinical evidence of adverse effects from doses of less than 0.05 Gy, said Dr Bilodeau. Almost all commonly used diagnostic imaging using radiation involves exposure well below 0.01 Gy. Imaging for pulmonary embolism is both safe and accurate, including a V/Q scan, a chest X-ray, and a chest CT if necessary. She warned that gadolinium contrast agent should not be used.

Ask about over-the-counter medications and supplements, especially herbal supplements, including dosage and frequency of use. The patient may not realize that any of these could impact testing and treatment

Courtney Bilodeau

'Make certain that a patient who is about to deliver has not received prophylactic dose anticoagulant medication within 12 hours, or therapeutic dose anticoagulant medication within 24 hours of undergoing regional anaesthesia. The patient needs to be eligible for regional epidural or spinal anaesthesia if needed during delivery,' she advised.

Additionally, medications should be ordered only if they are approved for pregnant patients and patients who are breastfeeding. Any medication risks should be discussed with patients in the context of risks that could occur if a patient does not take the prescription drug.

'Don’t trust the medication list on a patient’s hospital chart,' Dr Bilodeau said. 'Ask the patient if she is or has been taking “recreational drugs”. Ask about over-the-counter medications and supplements, especially herbal supplements, including dosage and frequency of use. The patient may not realize that any of these could impact testing and treatment.'

Lactation and breastfeeding: ‘Don’t assume anything’

'Lactation periods are also sensitive. Medications are more likely to be transferred into breast milk during the first to fourth day of lactation. Some women breastfeed their children for two years or more. Don’t assume anything,' she said.

'Finally, help a patient realize that her own health is most important,' Dr Bilodeau counselled. 'Patients will ask what risk they have. Make time to explain this in understandable terms. Advise that in any natural pregnancy, there is a 3% to 5% risk of congenital anomalies.’

References:

- Hoyert DL. “Health E-Stat 100: Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2023.” National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed online on June 1, 2025 at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2023/maternal-mortality-rates-2023.htm.

- Taylor J, Bernstein A, Waldrop T, et al. “The Worsening U.S. Maternal Health Crisis in Three Graphs.” The Century Foundation. March 2, 2022. Accessed online June 1, 2025 at https://tcf.org/content/commentary/worsening-u-s-maternal-health-crisis-three-graphs.

- Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data From Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 U.S. States, 2017-2019. CDC Maternal Mortality Prevention. May 28, 2024. Accessed online June 1, 2025 at https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-mortality/php/data-research/mmrc-2017-2019.html

Profile:

Courtney Clark Bilodeau, MD, is Associate Professor of Medicine and Clinical Educator in Obstetric Medicine and Breastfeeding Medicine at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, USA. She is also an attending physician at Brown University Health Obstetrics and Gynecology, and a certified lactation counsellor. Dr Bilodeau is a fellow of the American College of Physicians and a member of the North American Society of Obstetric Medicine, the International Society of Obstetric Medicine, and The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. Her clinical and research interests include breastfeeding, evidence-based complementary medicine, and peripartum management of chronic medical conditions from preconception through postpartum.

03.09.2025