Insulin regulates itself

In type 2 diabetes, which is occurring at alarming rates, the hormone insulin does not work effectively to lower blood sugars and patients also do not make enough insulin. These two processes have been widely considered as separate. However, a surprising discovery was made by Joslin Diabetes Center researchers in animal models of diabetes: insulin is important in regulating its own production. Confirming this discovery, Joslin clinical scientists have now gone on to show that when blood sugar levels rise in healthy people, insulin signals the cells that make insulin to increase their production.

Our bodies absorb sugar when we eat carbohydrates, and insulin acts as a "key" for the sugar to get into cells, where it provides energy for the cells to function. Sugar (also called glucose) acts as the main signal that tells insulin-producing "beta" cells, located in the pancreas, to boost their production of insulin. But insulin itself plays a role in signaling for this ramp-up, as the Joslin scientists have just confirmed in humans. Their investigation may aid our understanding of how insulin production eventually declines in type 2 diabetes, and raise the possibility of new types of drugs to prevent the loss of insulin production and to treat type 2 diabetes.

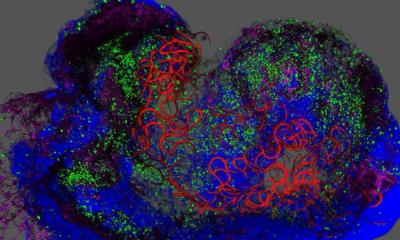

The clinical study builds on basic research that Joslin Principal Investigator Rohit N. Kulkarni, M.D., Ph.D., led a decade ago. Creating mice that were genetically modified so that their beta cells lacked an insulin receptor, Dr. Kulkarni found that like people with type 2 diabetes, the mice didn't make insulin properly as their blood glucose levels rose. Additionally, the mice often developed diabetes.

His work suggested that insulin resistance and insulin secretion, generally considered separate processes, are linked in beta cells. "But if insulin signaling is present and physiologically important in animals, is this also true in people?" asks Allison Goldfine, M.D., Joslin's director of clinical research and senior author on the paper, published online in PNAS Early Edition the week of February 15. "It was an important question because there are many differences between mouse and man. In people, insulin has long been thought to suppress the function of the beta cell, not to stimulate it."

Answering that question was no small feat. Joslin clinical researchers enlisted healthy volunteers and measured their insulin production under normal conditions. Then, under very careful control, the subjects received a human analog of insulin along with glucose via intravenous injections, with the investigators coordinating the doses to maintain normal glucose levels. Next the scientists upped the amounts of glucose and monitored the additional production of insulin—and found, indeed, that insulin production climbed faster when higher levels of insulin already were present.

The tests required careful use of assays that could differentiate between the administered insulin analog and insulin generated by the body. The scientists also did exhaustive studies that appeared to rule out other possible mechanisms for the boost in insulin production. To follow up, the Joslin clinical research team will study whether this insulin signaling mechanism appears damaged in people who manifest early insulin resistance, a condition that leads toward type 2 diabetes. "We've shown that insulin has a positive effect on its own secretion," says Dr. Kulkarni. "Our hypothesis now is that blunting of this positive effect in susceptible individuals may lead to a molecular cascade that eventually leads to poor function of the beta cells and then to type 2 diabetes."

If that hypothesis turns out to be correct, he says, it may offer opportunities to create new kinds of drugs for diabetes prevention and treatment.

SOURCE Joslin Diabetes Center

17.02.2010