Article • Microbiology & hygiene

HAIs are one problem – MDROs another

In view of the increase of multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO), the World Health Organisation (WHO) has declared antibiotic resistance one of the biggest threats to global health. MDROs have become a major problem particularly in hospitals.

Interview: Sascha Keutel

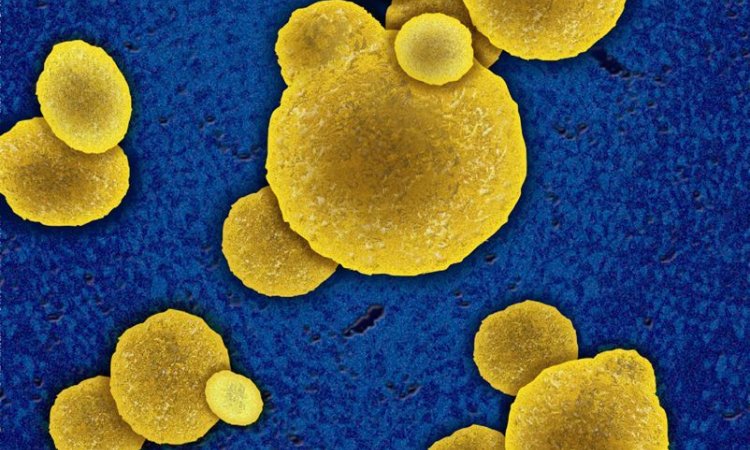

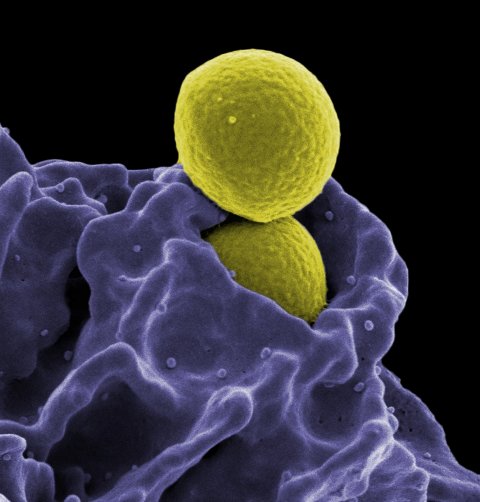

Source: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)

Professor Dr Georg Häcker, President of the German Society of Hygiene and Microbiology (DGHM) and Director of the Institute for Microbiology and Hygiene at the University Hospital Freiburg, explains some strategies to prevent hospital-acquired infections (HAI), also known as nosocomial infections, and to contain the further development of multidrug-resistant organisms.

Dr Georg Häcker: ‘Hospital-acquired infections are all infections acquired in or present in a hospital. They can be self-infections when the infecting organism is derived from the patient’s own skin, gastrointestinal or upper respiratory flora. A severely ill patient, for example, treated in hospital over a long period of time, might inhale bacteria from his or her own oral microflora into the lungs and develop pneumonia. This is also considered a nosocomial infection – and is one that can hardly be prevented.

‘HAIs, however, also can be transmitted from patient to patient, or from staff to patient, or they can be so-called environmental infections. Infections caused by sharing a toilet, or infections from staff to patient, to a large extent can be avoided. Complete prevention of all HAIs, however, is pretty much impossible since people and bacteria live at close quarters, so to speak.

‘The many routes of transmission pose many challenges and require a wide variety of measures. In some cases it might make sense to remove certain bacteria from the patient, in order to prevent self-infection. Staff, visitors and fellow patients must be instructed to follow simple hygiene practices, such as hand hygiene. The patient environment, such as tables, or the toilet as well as instruments and equipment with patient contact must be disinfected or sterilised according to a scientifically validated plan.

‘The patient microflora is most likely the biggest challenge because it can only be partially controlled and, obviously, cannot be removed. Implementation of effective hygiene measures in hospital routine, particularly in view of the often less than ideal working conditions, presents another problem.

‘It’s important to note that most HAIs are not caused by multidrug-resistant organisms. HAI and multidrug resistance are two distinct problems and the overlap of these problems – that is nosocomial infections caused by MDRO – is rather small.’

Are antibiotics still the only choice to fight infections?

‘The short answer is an unconditional “yes”! While some bacteria have developed resistance against all active substances, this does not mean that all bacteria are, or will become, resistant to all antibiotics. Case in point: penicillin. Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes used to be susceptible to penicillin; they had to develop resistance. Due to the medical use of penicillin, and related antibiotics, Staphylococcus has become resistant. Today, approximately 90 percent of Staphylococcus aureus in patient samples are penicillin-resistant. Streptococcus pyogenes, on the other hand, is still penicillin-susceptible. There are many different kinds of bacteria and they develop in very different ways with regard to resistance. As far as bacterial infections are concerned, antibiotics remain the first-line therapy and most bacterial infections can be successfully treated with antibiotics.

‘Having said that – there were indeed cases of bacterial infections where no antibiotic was effective due to resistance. In Germany, these cases are very rare, but in some regions of the globe the situation is serious. Therefore, it’s imperative that we try to contain the spreading of multidrug-resistant organism as much as possible. Most prognoses, for Germany and the entire world, see an increase in the number of infections that are difficult to treat or entirely untreatable.’

Is work to create new antibiotics and active substances progressing?

The one antibiotic that will effectively combat all bacteria is not in the wings

Georg Häcker

‘There are indeed some enhanced active substances and combinations of active substances that effectively combat certain highly resistant bacteria. Additionally, there are new active substances, or classes of active substances, against certain bacteria. For some bacteria no substance has been developed.

‘In general, this is a wide and complex issue. While it’s true that the development of antibiotics does not enjoy top priority among the large pharmaceutical companies, there is some research activity. It’s clear, though, that the one antibiotic that will effectively combat all bacteria is not in the wings. Bacteria will most certainly become resistant to the new antibiotics classes. Thus it’s of paramount importance to use antibiotics correctly and strengthen all elements of infection medicine.’

Recommended article

Article • Medication development

Support from the other end of the world

Partners who could hardly be further apart – yet have a lot in common – have united to fight resistant pathogens. The International Consortium for Anti-Infective Research (iCAIR) is based in Germany and Australia – separated by nearly 16,000 km as the crow flies. This has not stopped the research cooperation from achieving its objectives: the development of new agents against infections.

Are there no advances regarding total antibiotics resistance?

‘There is no single approach to solve the problem forever, but there are different approaches that help us to better understand the problem and evaluate the scope of the problem. Moreover, there are new ideas on how to strengthen healthcare structures to minimise the development and contain the spreading of antibiotics resistance. For some time, researchers have tried to use bacteriophages that infect and destroy bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics. This approach is promising but at this point it is too early to make any predictions regarding the possible success of such a treatment.’

What other strategies aim to stem the tide of MDROs?

‘The term “multidrug-resistant bacteria” encompasses heterogeneous organisms and is also used inconsistently. One of these bacteria is MRSA, which causes different problems in different countries. In Germany, the number of MRSA infections has been decreasing for a few years. The most troublesome are the so-called gram-negative bacteria, another heterogeneous group, since antibiotics are basically ineffective with all infections they cause. In some countries these bacteria are ubiquitous; in Germany they are either imported or home-grown due to antibiotics use.

‘Specific strategies tailored to different bacteria must be developed. Our most important “broad spectrum” strategy is strengthening and coordinating the three pillars of infection medicine: infections must be detected quickly and antibiotic susceptibility has must be determined quickly and reliably. This is the task of microbiology. Bacterial infections have to be treated quickly and correctly. This requires adequately trained physicians. Transmission of resistant bacteria between people, particularly in hospitals, must be avoided as much as possible – the task of hospital hygiene teams. The combination of these three strategies can reduce evolutionary pressure on bacteria and spreading of multidrug-resistant bacteria can be significantly contained.’

Should those strategies be applied on national/international levels?

‘Each country has its own native healthcare system, which is very difficult to influence by international efforts. Also, the resistance situation differs from country to country. Thus, national strategies that consider local structures are pivotal. At the same time, knowledge transfer is important, since not all countries have adequate mechanisms in place to map and understand multidrug-resistant organisms. We all have to try to use the knowledge that exists on the global level.

‘An internationally coordinated strategy would be helpful. Indeed, the key points have already been spelled out by WHO. But strategies that are successful globally not only need the political will but significant structural improvements and financial investments in the individual healthcare systems. Last, but not least, we need changes in lifestyles and our perception of the issue. We have to work on these strategies without falling prey to the illusion that they can be implemented quickly and that they will quickly yield major results on the global level.’

Profile:

Professor Georg Häcker MD gained his doctorate in medicine in 1991, at the University of Ulm, Germany. Today, he presides over the German Society of Hygiene and Microbiology (DGHM) and is Director of the Institute for Microbiology and Hygiene at Freiburg University Hospital. In his research he focuses on the molecular mechanisms of cell death, cell death in the immune systems and the infection biology of Chlamydia trachomatis.

22.07.2019