News • Hospital hygiene

Will resistant bacteria be the end of alcohol hand sanitizers?

Alcohol-based hand sanitisers have been a mainstay in hospital hygiene for decades. But now, strains of antibiotic-resistant bacteria show signs of overcoming these handwashing agents as well. Does this mean we should just stop sanitising our hands?

For many years, the front-line in the battle against antibiotic-resistant bacteria has been alcohol-based hand sanitizers and cleaning liquids that effectively kill bacteria before they can get close to infecting vulnerable patients. But now the bacteria are fighting back. New strains have an increased tolerance to the alcohols in sanitisers. A new study by the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity and Austin Health published in Science Translational Medicine has found that strains of Enterococcus faecium, a notorious healthcare-associated bacterial pathogen, have emerged since 2010 that are ten times more tolerant of alcohol-based hand rubs than older strains.

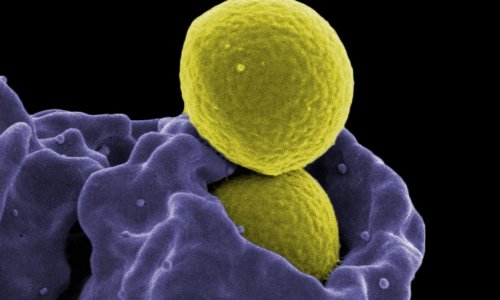

A strict regime of hand washing with alcohol-based sanitizers before and after patient interactions has been in place in hospitals around Australia, and many other countries, since 2002, to curb a rise in deadly MRSA, an antibiotic resistant form of Staphylococcus aureus (golden staph).

Anywhere we repeat a procedure over and over and over again, whether it’s in a hospital or at home or anywhere else, you’re giving bacteria an opportunity to adapt

Tim Stinear

But while rates of golden staph infection have been decreasing for the last 15 years, a new threat emerges: Enterococcal bacteria, which are a normal part of the human gut bacteria and don’t usually cause health problems, are becoming more prevalent in hospitals and can cause infections that are very difficult to treat. Especially bacteria of the species Enterococcus faecium seem to thrive, leading to increased number of infections.

One particularly problematic group of enterococci are those that develop resistance to the last-line antibiotic, vancomycin. These bacteria are known as vancomycin resistant enterococci (VRE). These are particularly dangerous for patients undergoing antibiotic treatment, because the medication takes out their gut microbiome. “When your natural gut bacteria are disturbed you can become prone to VRE, in the context of a health-care institution”, says Professor Tim Stinear from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity. The research team took 139 different strains of E. faecium and treated them with isopropanol solution, an alcohol commonly used in hand sanitisers. “We started testing to see whether they had any tolerance to alcohol, and sure enough, the new isolates were more tolerant to alcohol exposure than the older isolates.”

Professor Stinear says this is an unfortunate side effect of the success of the hygiene program. “Alcohol use in hospitals has gone from hundreds of litres a month to thousands of litres a month of these alcohol-based disinfectants. “Anywhere we repeat a procedure over and over and over again, whether it’s in a hospital or at home or anywhere else, you’re giving bacteria an opportunity to adapt, because that’s what they do, they mutate. The ones that survive the new environment better then go on to thrive.” And the risk increases when the guidelines aren’t followed.

Source: Pixabay/falco

We can’t rely solely on alcohol-based disinfectants and for some bacteria, like VRE, we’re going to need additional procedures and policies in place

Tim Stinear

“Anywhere you have sub-optimal contact times with the full-strength product you’re going to risk some breakthrough, or bacteria persisting.”

The researchers also looked for clues to the alcohol resistance in the bacteria’s genome. “We looked for signatures in the genome of the bacteria of adaptation, and we found them” said Professor Stinear. “We could see that there were genes that looked to be under evolutionary selection and those genes, when we mutated them, changed the alcohol tolerance of the bacteria.”

These results will help researchers to understand the mechanism of alcohol resistance. “This isn’t the end of hospital hand hygiene, that’s been one of the most effective infection control procedures that we’ve introduced worldwide,” says Professor Stinear. “But we can’t rely solely on alcohol-based disinfectants and for some bacteria, like VRE, we’re going to need additional procedures and policies in place. For hospital this will be super-cleaning regimens, which include alternative disinfectants, maybe chlorine-based. An extra level of infection control, that doesn’t just rely on alcohol-based disinfectants is required.”

Source: University of Melbourne

07.08.2018