Article • Medication development

Support from the other end of the world

Partners who could hardly be further apart – yet have a lot in common – have united to fight resistant pathogens. The International Consortium for Anti-Infective Research (iCAIR) was founded last January.

Report: Wolfgang Behrends

Hanover Medical School (MHH) and the Fraunhofer-Institute for Toxicology and Experimental Medicine (ITEM) are participants in Germany. The third partner, the Institute for Glycomics (IfG) at Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia, is nearly 16,000 km away as the crow flies. That enormous distance has not stopped the German-Australian research cooperation from achieving its objectives: the development of new agents against infections. Professor Armin Braun, Head of Preclinical Pharmacology and In Vitro Toxicology at Fraunhofer ITEM, explains the specific potential of this long-distance alliance.

The idea behind iCAIR is simple. The partners combine their respective strengths to create a project that’s more than the sum of its parts. IfG Director Professor Mark von Itzstein contributes considerable expertise in the development, design and optimisation of substances; he was a major driver behind the development of Relenza, a highly effective ’flu medication. ‘However, what was missing from his side was the translational aspect relating to toxicology, quality assurance and preclinical proof-of-concept,’ Braun explains. ITEM and MHH will contribute this know-how.

Where pharmaceutical firms pull out, others step in

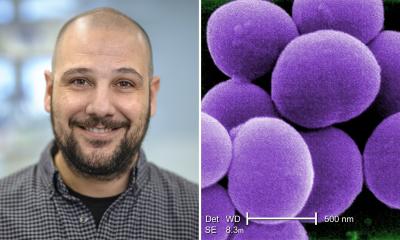

Making do without the development of new anti-infectives, only because the pharmaceutical industry cannot find the right business model, is no alternative

Armin Braun

The partners are funding the project. Fraunhofer finances the iCAIR programme; MHH and IfG fund their own projects. This financial autonomy is central to the consortium, Braun explains. ‘The pharmaceutical industry has now largely scaled down development of anti-infectives. However, iCAIR facilitates the development of new substances beyond commercial interests. Research is to be refinanced via own patents. Making do without the development of new anti-infectives, only because the pharmaceutical industry cannot find the right business model, is no alternative.’ Alternative sources of finance, such as the Gates Foundation, public funding from the BMBF (Federal Ministry of Education and Research) or the iCAIR alliance, are the way forward in this situation

Different pathogen – similar methods

The need for new anti-infectives is substantial: Bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Neisseria meningitidis, the mould Aspergillus fumigatus, as well as influenza and para-influenza viruses are an international problem. ‘Anyone, anywhere in the world, can become infected with influenza, and the changes in social structures are increasing the problem. People are living longer and are thus more prone to infections.’ The growing number of immunosuppressed patients and those who have received organ transplants also offer pathogens new scope for attack. ‘There are hardly any effective drugs against fungal infections in particular, which is why survival rates for outbreaks on the ICU are frequently very low.’

A dizzying pace of drug development

iCAIR’s biggest progress is in new agents to fight influenza. The preclinical proof-of-concept stage has been reached and the first drugs could be ready for clinical use in 2-3 years. By pharmaceutical standards, where development cycles can be 15 years or longer, this constitutes an almost dizzying pace. ‘Although this does not apply to all substances,’ the professor points out, ‘we can usually shave off around 1-3 years.’ This optimisation is achieved through clever division of labour: MHH and IfG concentrate on the identification of possible drug targets. The Australian partner selects and generates the substances from which new pharmaceuticals are to be developed. The subsequent preclinical phase is in the realm of Fraunhofer ITEM, which will also support the further clinical development and production of the substance.

Although the partners are at opposite ends of the world, the cooperation works very well, Braun explains. ‘The fact that all those involved are professionals – some with decades of experience in their area of expertise – makes the cooperation really enjoyable.’ The new iCAIR consortium is already receiving good feedback from experts; several research institutions worldwide have expressed interest in participation. In the long term, this additional expertise and resources should help to develop a global network for the joint development of anti-infectives.

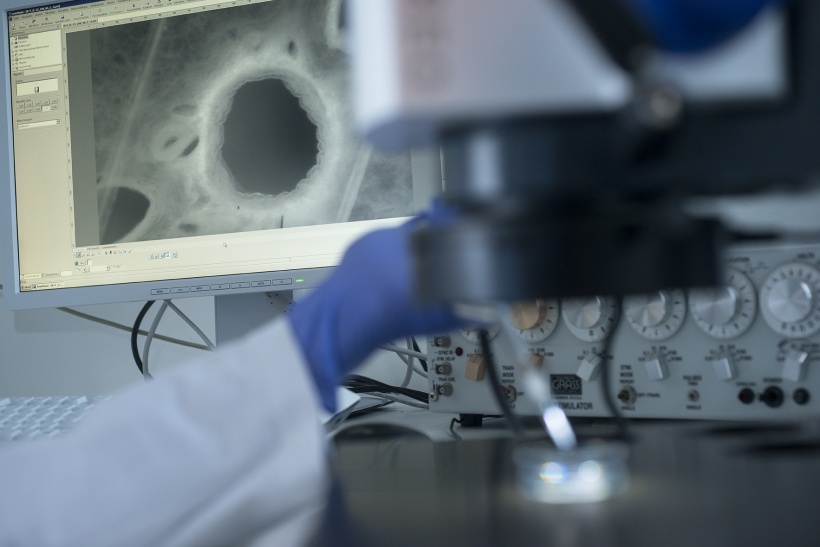

The current leading topic at iCAIR is new substances against influenza: ‘Germany as well as Australia recently had huge problems with ’flu epidemics because vaccines are not effective,’ Braun points out. Meanwhile, although there has been a paradigm shift that promises improvements, ‘we are no longer fighting the pathogens directly but are working on the viruses entry ports into cells. Researchers test their agents on human tissue taken from tissue slices, such as healthy parts of tissue obtained during tumour resection. This is a completely new approach for us,’ Braun notes. The tissue sample is infected with viruses and kept alive for several weeks to observe interactions between tissue and pathogen. ‘This is a model which comes very close to the actual reaction occurring in the human body.’

Profile:

Dr Armin Braun is head of Preclinical Pharmacology and In Vitro Toxicology at the Fraunhofer-Institute for Toxicology and Experimental Medicine ITEM, in Hanover, and professor of Immunology of the Respiratory Tract at Hanover Medical School (MHH). A member of the German Centre for Lung Research (DZL), his research focuses on the preclinical development of substances against respiratory diseases. He uses innovative processes such as live tissue slices (precision-cut lung slices; PCLS). Braun has co-authored more than 150 scientific articles in international scientific publications.

21.04.2018