Interview • Tumour triggers

Can cancer be contagious?

No self-respecting TV crime series is without a pathologist – but the fictitious pathologist who incessantly solves crimes has little to do with reality.

Interview: Sascha Keutel

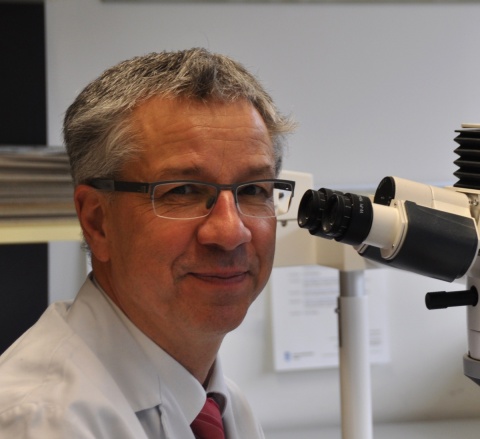

‘More than 95 percent of our time is dedicated to living people,’ explains Professor Gieri Cathomas, Medical Director of the Institute of Pathology at Kantonsspital Baselland, Switzerland. Today, pathology is a clinical pillar of tumour management, from diagnosis through to therapy decisions to prognosis. But the specialty is not only tumours: ‘It’s important to mention that pathology also deals with infectious diseases,’ the professor adds. ‘We can contribute significant knowledge on the role of pathogens in general human diseases, including tumour development.’

‘Cancer is a genetic disease and the result of an accumulation of genetic changes in our cells,’ explained pathologist Professor Gieri Cathomas, when asked how cancer develops and what role pathogens play. ‘Infections are involved in about 15 percent of all tumours that develop – with significant regional differences. The most important pathogens are viruses, such as the human papilloma virus that can cause cervical cancer or the hepatitis B and C viruses that cause chronic liver infection. Moreover, there are certain bacteria and parasites that play a role in tumour development. However, in most cases a viral infection alone won’t trigger cancer and fortunately most people who do get infected won’t develop a tumour. It is only a long-term infection that may lead to genetic changes that then cause tissue degeneration.’

Infection-associated tumours? Could cancer be contagious?

‘Cancer is not a contagious disease. Thus a person who cares for a cancer patient won’t ‘catch’ the disease. The cancer, as such, is not contagious. This has to do with the fact that the viruses in the tumours have undergone changes and cannot proliferate. However, pathogens, like all infectious agents, are transmissible. Therefore we may indeed call certain tumours infectious.’

Which pathogen pathways and mechanisms could trigger cancer development?

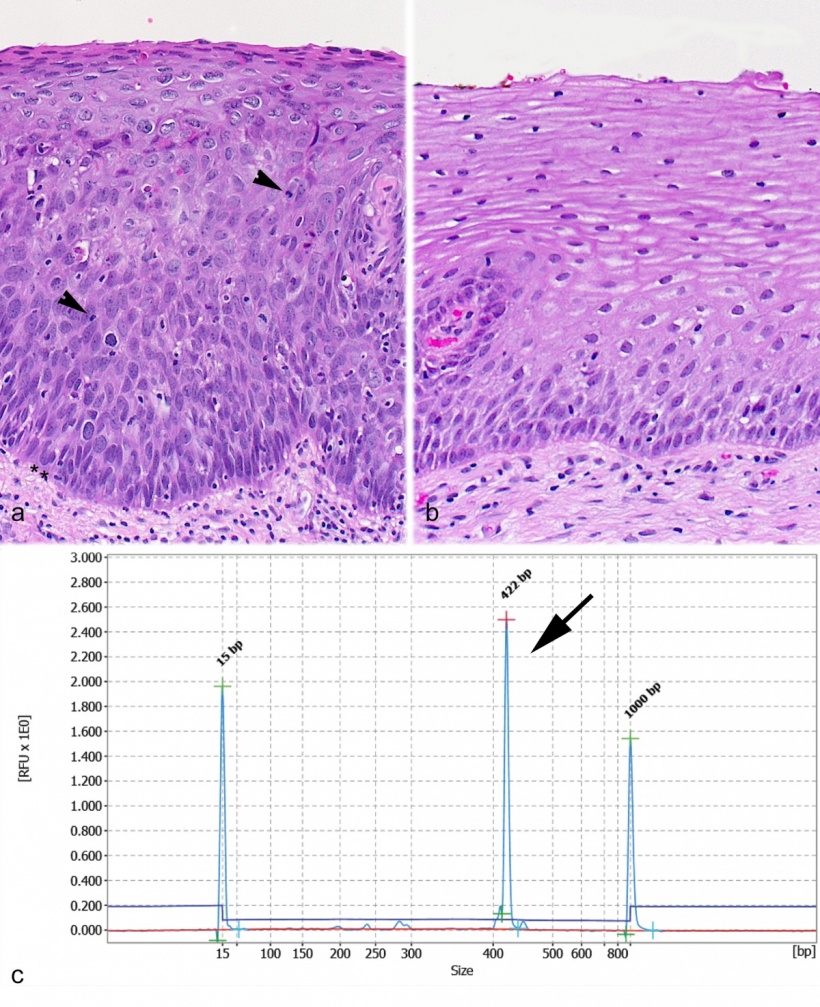

‘Sexual transmission and transmission by blood products are the two most frequent viral pathways, but certain pathogens can also spread by everyday human contact. In an infected human the infection has to last very long, and most of the time our immune system keeps infectious agents from taking hold. In a persistent infection, viral genes interact with cell genes, to be precise: the genes that regulate cell proliferation are activated or deactivated. This causes genetic instability of the cell, which in turn triggers an accumulation of genetic changes that lead to the development of cancer. Another mechanism is a chronic inflammation caused by the pathogen, such as chronic liver inflammation after a hepatitis B and C infection. These chronic inflammations frequently lead to the damage and loss of liver cells. Consequently, new cells have to be produced incessantly and at a sometimes enormous speed which leads to genetic defects and tumours.’

How do we benefit from knowledge about infection-associated tumours?

‘This knowledge helps us with regard to prevention, early detection, diagnosis and therapy of pathogen-associated tumours. Let’s take the human papilloma virus in cervical cancer. The so-called Pap test is a very sensitive test for the early detection of cervical cancer.

‘Prevention is the best therapy – that saying also holds true for tumours. If the cause, such as a virus infection, is known, it can be prevented by vaccination, as has been show in vaccination against hepatitis b and human papilloma virus. A further – individual – strategy to prevent infectious tumours is personal hygiene, particularly with regard to sexual intercourse, such as safe sex. This helps each of us to reduce the risk of such tumours.’

Vaccination is a very efficient and long-term method to prevent infection-induced cancer

Professor Gieri Cathomas

You mentioned viral infections as tumour triggers, what about bacteria?

‘Bacteria are a more complex issue. Every human being is colonised by many, many bacteria, be it on the skin, the mucous membranes, or in the intestinal tract. There are more bacteria in our colon than cells in our body. These colon bacteria, however, are highly desirable ‘residents’ since they contribute to our health. Other bacteria are ‘undesirables’ since they can cause acute and chronic diseases. Point in case: helicobacter colonises the stomach. During an infection tissue can be damaged and needs to be regenerated. As with the production of liver cells mentioned before this continuous and rapid process may cause a genetic instability, which triggers increased cell growth and a degeneration.’

In your crystal ball – what do you see happening over coming years in terms of pathogen-associated tumours?

‘Vaccination is a very efficient and long-term method to prevent infection-induced cancer, as can be seen in the case of papilloma virus and cervical cancer or hepatitis B virus and liver cell carcinoma. I do hope that further vaccines, for example against hepatitis C or helicobacter, will be developed.

Another possibility is targeted therapy aiming at the pathogen itself. Today, modern technology, such as deep sequencing, allows us to read very large numbers of genes and their composition very quickly. Recent research has indicated that the composition of our enteric flora influences the development of colon cancer. This knowledge might enable us to identify people with an increased risk of colon cancer. In the medium to long term, we might be able to reduce the cancer risk by changing our individual diets.’

Profile:

Professor Gieri Cathomas is Medical Director of the Institute of Pathology at Kantonsspital Baselland, Switzerland. In 1987 he received his doctorate from the Institute of Medical Microbiology at the University of Basle for his dissertation comparing different methods of electron microscopic virus diagnostics. His habilitation thesis in general and special pathology, submitted in winter 1998/99 to the University of Zurich, dealt with the role of virus detection in bronchial lavage and tissue for the diagnosis of cytomegalovirus and herpes virus 8 infections and diseases in immunosuppressed patients.His research focuses on the pathology of non-tumorous and tumorous lesions of the gastrointestinal tract, infection-associated tumours and the diagnostic detection of pathogens in tissue.

27.04.2016