Why screen?

The on-going debate

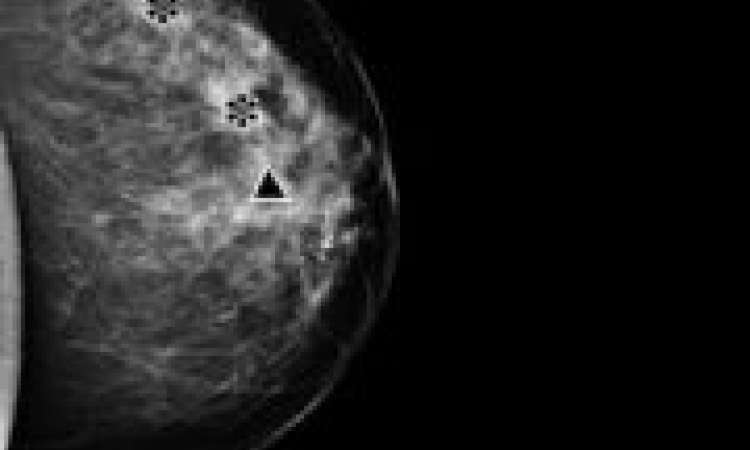

Mammography as a diagnostic procedure to evaluate detected tumours is not an issue. But because the technique is performed, in screening programmes, on apparently healthy people, for ethical reasons it becomes an issue.

Screening should be based on a sound scientific foundation, so results from several studies of mammographic screening need critical re-evaluation of this procedure, according to Professor I Mühlhauser, specialist in internal medicine, diabetology and endocrinology at Hamburg University, Germany.

Using an evidence-based approach, Danish researchers Peter Goetzsche and Ole Olsen evaluated all available data on mammographic mass screening. They concluded that there is no reliable evidence that regular mammograms reduce breast cancer mortality and argue that six in eight studies showed flawed methodology, questioning the reliability of their results. Two studies that were reliable, i.e. meeting the strict criteria of the Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, indicated that mammographic screening does not yield any benefits (The Lancet 2001; 358, 1340-1342).

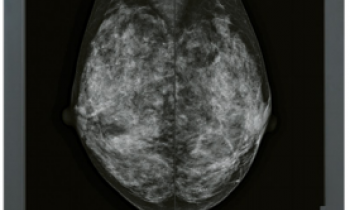

In Sweden, mammographic screening began in the late 80s. The study included 600,000 women aged 50-69. A recently published analysis of the data raised doubts on the usefulness of these expensive screening programmes, because, from1986-96 breast caancer mortality had not significantly decreased in the region. The number of deaths from breast cancer in the group of women who had undergone mammographic screening was only 0.8 % below the expected value (British Medical Journal 1999; 318: 621).

Both findings, published in renowned medical journals, are disquieting in themselves, but worse, Professor Mühlhauser points out, is that screening may have negative effects: wrong results, be they positive or negative. Incorrect positive findings lead to unnecessary interventions and create fear in the women concerned; incorrect negative findings create a false sense of security. In the Swedish study, 100,000 women received an incorrect positive diagnosis and consequently biopsies for further clarification were performed on 16,000 women. 4,000 women underwent unnecessary surgery, in many cases even a mastectomy.

These findings should influence the design of future screening programmes. Comprehensible and objective information for the public must include the possible benefits as well as possible harm. Only then can all findings can be evaluated and analysed. One feature of mammographic screening is that many women participate; some benefit and many suffer serious harm. Women can only make an informed decision if they can assess personal benefits in relation to effort and effect.

The primary goal of screening is to achieve a decrease in mortality - while maintaining an acceptable level of quality of life, effort and cost. Data presentation influences the decisions of women and doctors. What does it mean, when mammography allegedly reduces breast cancer mortality by 30%? Most people would assume that, out of 100 women, 30 fewer die from breast cancer. But that is not the case. Absolute figures are far more transparent.

There are different ways to present data in favour of early detection screenings. Often, results are being shown in percentages. Using Swedish data Mühlhauser illustrates the danger inherent in different presentations: Without mammography four out of 1,000 women die of breast cancer within a 10-year period. With mammography, the number is reduced to three. In absolute figures: Without mammography 996 women don’t die from breast cancer over a period of ten years. With mammography the figure is 997. Or: Out of 1,000 women with mammography one woman benefits by not dying of breast cancer, 999 women have no benefit as they would not have died from breast cancer anyway (996 women) or because they died from breast cancer despite mammography (three women).

Further details:

www.mammographie-screening-online.de

www.gmc-uk.org/standards/CONSENT.htm

01.07.2004