Source: Pexels/Nashua Volquez

Article • Meeting of the generations

We need a Senior Laboratory

It’s undeniable: the bulk of our population is growing older. Yet, this demographic change has not altered laboratory medicine: the reference values for many analyses are still based on data of a younger cohort. Inevitably this could lead to serious errors in the interpretation of older patients’ test results. Professor Kai Gutensohn, Managing Director and Medical Director of AescuLabor Hamburg, Germany, points out some of the differences between old and young – and how these should be reflected in lab diagnostics.

Report: Daniela Zimmermann

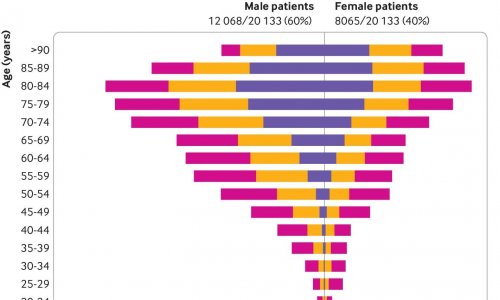

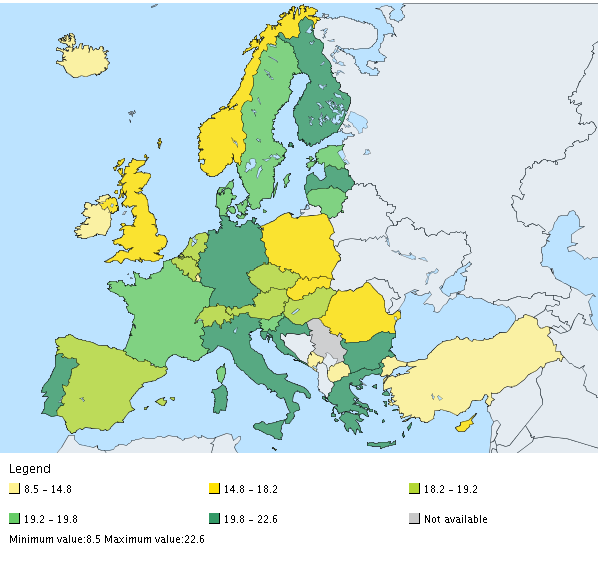

According to European Commission statistics for 2017, the 65+ age group currently accounts for around 19.5 percent of the EU population. This percentage will increase and it is expected that particularly the number of octogenarians will rise dramatically over the next few decades. ‘This shows how urgently we need geriatric medicine,’ says Dr Kai Gutensohn. ‘In these age groups, many diseases manifest themselves quite differently than among younger people – which makes correct diagnoses so much more difficult. Lab medicine needs to address the topic of ageing in quite a fundamental way. What we need is a kind of senior lab.’

One basic problem is reference values: ‘Lab analytics defines ranges that are considered the ‘norm’. However, these values are mostly generated from 20 to 40-year-old patients. This raises the question of whether the reference values in labs are applicable to older age groups.’ In haematology, for example, age-specific values were established for the age group 1 to 18, but not for older patients. This is even more alarming, Gutensohn explains, in view of the very significant differences, for example, between ‘young old people’ (65-74 years), ‘aged’ (75-84) and ‘elderly old’ (85+). He also points out: ‘There is only a weak correlation between the date of birth and biological age.’ This affects, among others, pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenomics, since many drugs show different effects in younger and older bodies.

Source: European Commission / Eurostat (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/); as of 2018

Multimorbidity and polypharmacy broaden the range

Significant differences between old and young can also be traced back to the higher prevalence of chronic diseases and multimorbidity as Gutensohn says: ‘In many over 65-year-old patients three or more conditions coexist.’ In older patients, the main causes for consulting a physician are dizziness and shortness of breath, followed by heart issues and back pain and well as blood pressure issues. All these can be caused by a number of age-typical conditions such as diabetes mellitus, heart disease, hypertension, diseases of the bones and tissues, arthritis, bronchitis and ’flu. Multimorbidity often leads to concurrent use of multiple medications – thus polypharmacy has to be considered in the diagnostic work-up of older patients.

To a great extent patient age determines the kind of relevant tests in lab diagnostics: ‘For children and young adults basic lab tests, allergies and certain microbiological tests are common. However, in the 65+ patient group the focus is more likely to be on haematology, protein diagnostics, medication level and auto-antibody testing.’ Moreover, prevention becomes an important issue, for example measuring glucose and lipids for diabetes prevention of screening for malignant diseases. PSA levels might indicate prostate cancer. The reference values, however, are clearly age-dependent and if age is not adequately considered the wrong treatment or therapy may be prescribed.

Small effort, huge benefit

Today lab diagnostics for dementia might be ahead of therapy, but it may well be that in a few years an effective therapy will be available

Kai Gutensohn

‘Lab tests in geriatric medicine are invaluable, since they offer varied input that helps to ascertain the diseases of the 65+ cohort and thus to determine adequate treatment,’ Gutensohn points out. Rather simple lab tests can show asymptomatic diabetes, which could cause severe damage. The individual patient, as well as the healthcare system at large, thus profit from such tests, he emphasises. ‘Lab diagnostics is the foundation – with €8.5 billion per year, it only accounts for 2.5 percent of the annual healthcare spend, but affects 60 to 70 percent of all diagnostic and therapy cases.’ Since a major share of healthcare resources are used for older people, the diagnostic and treatment options, he believes, should be better aligned with this group.

However, why strive for the early detection of diseases that cannot be cured anyway – such as Alzheimer’s? Even in those cases, Gutensohn says, lab tests are beneficial for patients: ‘Today lab diagnostics for dementia might be ahead of therapy, but it may well be that in a few years an effective therapy will be available.’ Such progress – driven also by high-throughput procedures, multiparametric analyses and big data-based algorithms – is very real, he points out. Moreover, today many diseases might not be curable but nonetheless early detection can increase the quality of life, Gutensohn underlines. ‘Take anaemia – the most frequent lab diagnosis in older patients. If detected early on, a few simple measures, such as prescribing iron or vitamins as long as there is no significant further underlying disease, can do a lot of good and enable the patient to live a long and autonomous life.’

Profile:

Dr Kai Gutensohn is Managing Director and Medical Director of AescuLabor Hamburg as well as Managing Director of Laboratory Group North of amedes GmbH. He has a board degree in laboratory medicine, transfusion medicine, hemostaseology, is health economist and professor at the Medical School of Hamburg University. He holds a number of honorary roles, e.g. with the Krankenhaus-Kommunikations-Centrum (KKC), which aims to promote interdisciplinary cooperation in healthcare. He is also a member of several medical societies and associations, such as the – German Association of Laboratory Medicine (BDL); the Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis Research (GTH); the German Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (DGKL) and the German Society for Haematology and Oncology (DGHO) and the IGLD, Germany’s largest group for laboratory medicine.

03.04.2019