Neurology

Tracing the scent of fear

The odor of bobcat urine, if you ever get a chance to take a whiff, is unforgettable — like rotten meat combined with sweat, with something indescribably feral underlying it. To humans, it’s just nose-wrinklingly disgusting. But to mice, it smells like one thing: fear.

Rodents respond instinctually to this trace of their natural predator. Even those mice raised in the lab, which have never been exposed to bobcats — or cats of any sort — respond to it.

For mice, this instinctual reaction can be lifesaving. The fear response triggers a surge of stress hormones which sends the mice into hyper-preparedness, helping them to respond and flee quickly from hungry predators. Although humans and mice have different stress triggers, this response is reminiscent of our physiological responses to fear and stress.

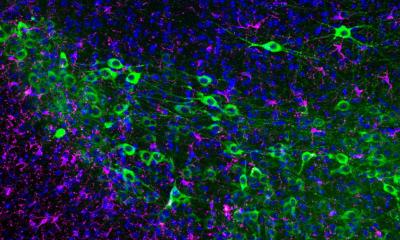

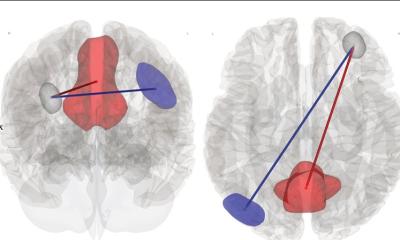

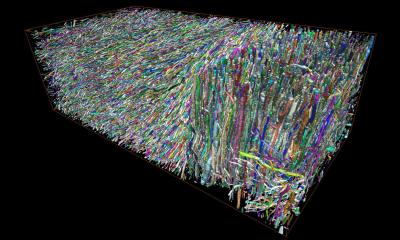

Now, a study has identified nerve cells and a region of the brain behind this innate fear response. With a new technique that uses specially-engineered viruses to uncover the nerve pathway involved, a research team led by Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center biologist and Nobel Prize winner Dr. Linda Buck has pinpointed a tiny area of the mouse brain responsible for this scent-induced reaction.

It’s known as the “amygdalo-piriform transition area,” or AmPir for short; the researchers were surprised to find that the fear response was so concentrated in this one small region of the olfactory cortex, a part of the brain responsible for perceiving odors.

Although humans do not show innate fear to predator odors, studying how mice respond to predator cues can help us learn about our own innate emotions and responses, Buck said. On a general level, the rodent stress response looks a lot like our own.

“Understanding the neural circuitry underlying fear and stress of various sorts is very important, not just to understand the basic biology and functions of the brain, but also for potentially finding evolutionarily conserved neural circuits and genes that play an important role in humans,” said Buck.

Source: Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

24.03.2016