Could the virus endanger Europe?

The welcome logic of a World Bank expert

‘Ebola does not present a direct epidemiological danger for Europe,’ according to Dr Armin Fidler, Lead Advisor on Policy and Strategy at the World Bank, but, he added, ‘Inevitably some Europeans will become infected with Ebola, such as those in the healthcare professions or aid workers.’

Report: Michael Krassnitzer

Dr Fidler made that statement when interviewed by European Hospital during the European Health Forum Gastein, in very early October – well before the first known case of an Ebola infection in Spain emerged.

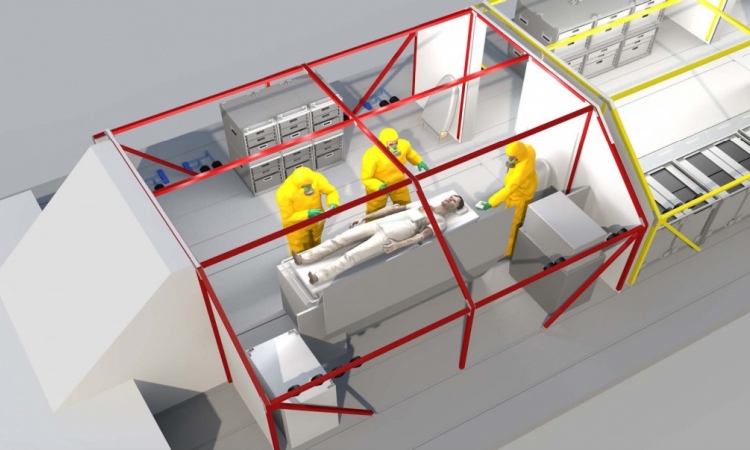

‘Numerous current analyses and commentaries assume that Ebola could be quickly and effectively brought under control if the disease had not started in three West African states but for instance in a European country,’ he explained. In countries with highly developed healthcare systems, people with suspected infections can be quickly and consistently isolated. Health service providers are adequately equipped to minimise the risk of contagion. Doctors and nurses can offer the best possible treatment, such as treatment for dehydration, impaired liver and kidney function, bleeding and impaired electrolyte metabolism.

‘Contaminated materials can be appropriately disposed of and there is extensive information available to the public on the disease, its transmission and the correct behaviour during an Ebola epidemic.’

However, Ebola does indeed pose an indirect danger for Europe, as Fidler explained: The disease has a destabilising effect on those countries already known as fragile states: ‘If these countries experience political unrest or waves of refugees this would obviously also have political or economic consequences for Europe.’

‘The problem around Ebola is an indication of the fact that there has not been enough long-term and sustainable investment into the healthcare systems in these countries over the last few decades,’ he stressed. ‘The main investment has been into quick wins, i.e. areas where it’s easy to quickly achieve positive results.’

Development aids in the healthcare sector, he said, are often earmarked for projects and measures that are comparatively easy to implement and effective in the short term, such as against HIV/AIDS. ‘In vaccination programmes, for instance, results are easy to measure.

It’s easy to estimate how many lives have been saved. These projects are important, but there is also a need for systematic, long-term and strategic investments into the healthcare system.’

Some damaging effects

‘Many of these funds develop parallel structures, with doctors and nurses enticed away from the public sector because pay is better.’ Long-term investment in healthcare systems is not as ‘sexy’ and harder to evaluate. In human resources investment, it takes a decade to train a doctor, which covers two legislative periods – ‘so no politician would be interested,’ he said.

Furthermore, health also depends on structures that appear to have nothing to do with a healthcare system. Fidler mentioned containers filled with medical supplies decaying in a harbour because the authorities are inefficient or corrupt: ‘People in highly developed countries find it hard to perceive that investments into harbour and customs administration are also important their healthcare system.’

The agenda for Ebola is obvious to Fidler. There is an urgent need for additional healthcare providers who need to be adequately supported. The affected countries also need more mobile laboratories, hospitals and rapid tests, but also more communication about the disease, spread and treatment. ‘Theoretically, it should not be difficult to stop the epidemic – if we succeed in isolating people with suspected infections or those who have been in contact with people who have had the disease diagnosed.’

However, the situation will become critical if the disease reaches the slums of a large African city with millions of inhabitants: ‘The worst-case scenario assumes a potential 1.4 million cases by the end of the year. We all hope this will not happen.’

PROFILE:

Armin Fidler MD MPH MSc, who joined the World Bank in 1993, is Lead Adviser on its Health Policy and Strategy, based in Washington D.C. A medical graduate from Innsbruck University, he also holds Masters in Public Health (MPH) and Science (MSc) in Health Policy and Management, both from Harvard University’s School of Public Health. Dr Fidler studied management at Harvard Business School and Public Finance and Welfare Economics at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

30.10.2014