News • Coital research

'Sex in an MRI scanner' – the story behind an extraordinary imaging project

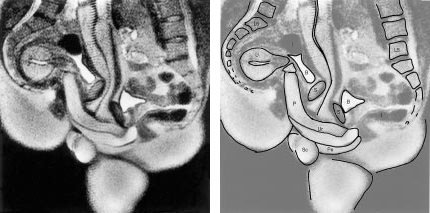

This Christmas marks the 20th anniversary of the publication of “Magnetic resonance imaging of male and female genitals during coitus and female sexual arousal” in The BMJ.

In its first year, it picked up the IgNobel prize for medicine, and has since become one of the most downloaded BMJ articles of all time. Dr Tony Delamothe, a former editor at The BMJ, ponders on its success. In celebration of the article's anniversary, his thoughts are published in a special feature in The BMJ.

Image source: Dickinson RL. Human sex anatomy, a topographical hand atlas. 2nd ed. London: Baillière, Tindall and Cox, 1949:84109 (Editing: HiE)

Despite some setbacks (reluctance by hospital officials; “sniffing press hounds” and some problems with sexual performance), the researchers were able to achieve good images of coitus in progress. The main findings, based on 13 experiments performed with eight couples and three single women, were that during intercourse in the “missionary position” the penis is neither straight nor "S" shaped as had been previously thought, but is, in fact, the shape of a boomerang. What’s more, during female sexual arousal the size of the uterus does not increase, as had been previously reported.

The researchers concluded that taking magnetic resonance images (MRIs) of the male and female genitals during sexual intercourse is feasible and adds to our knowledge of anatomy.

[The study contained] a striking image using a new technology, and everyone agreed that readers might be interested to see it

Tony Delamothe

At the time, nobody at The BMJ thought the study was particularly useful clinically or scientifically, but it contained “a striking image using a new technology, and everyone agreed that readers might be interested to see it,” writes Delamothe. It was hardly the medical equivalent of a moon landing, so why did “lay” visitors come flocking in such numbers? He suggests that the prospect of seeing coitus on screen (for free) was the attraction, even if all that was on offer was a series of black and white still photographs. “If that’s the explanation, it’s hard to think ourselves back to such an innocent age, given today’s explicit online offerings,” he says. Nevertheless, the “sniffing press hounds” have kept interest alive these past 20 years, regularly rediscovering the original paper and sending new generations to it.

Image source: Schultz et al., 1999, The BMJ

He points out that the IgNobel awards are given to articles that make you smile, then think. How much thinking this article has occasioned since publication is moot, he writes. But it is still making people smile (and laugh), much to the annoyance of author and participant Professor Ida Sabelis. She despairs that friends, family, and even colleagues at VU University in Amsterdam - one of the world’s most progressive cities - still find the study amusing. “Why that’s the case, 20 years after the article’s original publication, is worth a study of its own,” concludes Delamothe.

Source: The BMJ

Recommended article

News • Physical contact research

Two people, one MRI: The science of cuddling

Researchers at Aalto University and Turku PET Centre have developed a new method for simultaneous imaging brain activity from two people, allowing them to study social interaction. In a recent study, the researchers scanned brain activity from 10 couples. Each couple spent 45 minutes inside the MRI scanner in physical contact with each other. The objective of the study was to examine how social…

19.12.2019