Image credit: Brain Tumour Research Centre of Excellence at Queen Mary University of London

Article • Glioblastoma analysis

Revealing tell-tale signs of deadly brain cancer

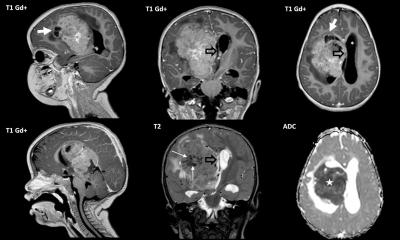

A new way of differentiating healthy from diseased cells could pave the way for more personalised treatment for patients diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), a common and aggressive type of brain tumour.

Report: Mark Nicholls

The approach, discovered by a team from the Brain Tumour Research Centre of Excellence at Queen Mary University of London, may help predict a patient’s response to drugs currently in clinical use for other diseases. These could then be repurposed for individualised GBM treatment.

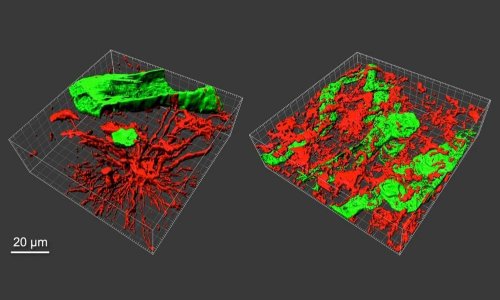

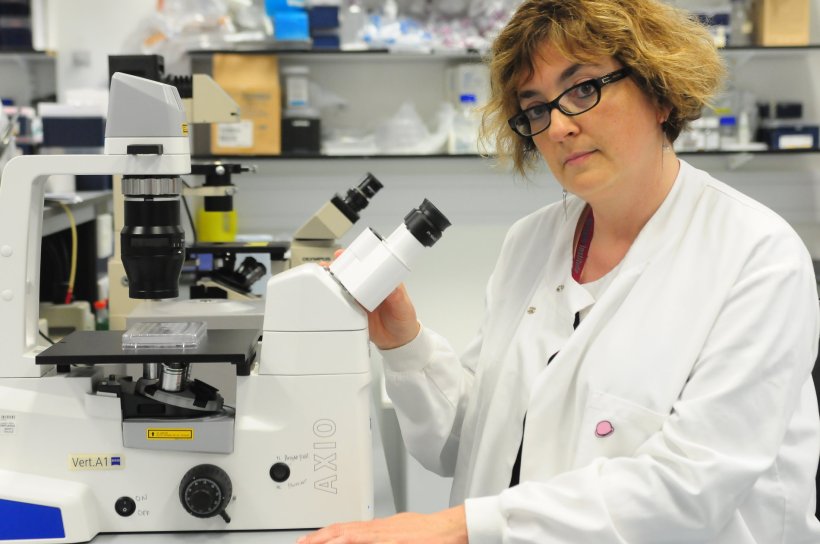

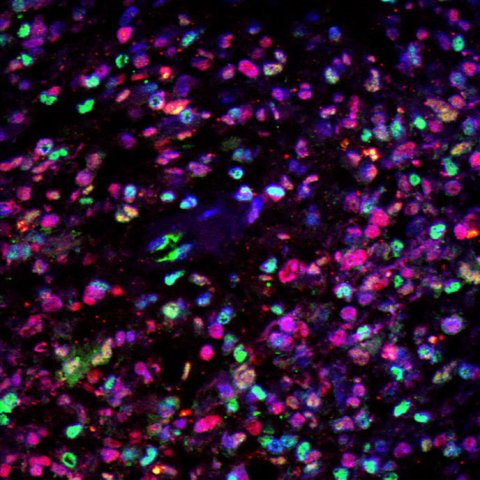

The basic idea – syngeneic comparison of glioma-inducing cells (GIC) and induced neural stem cells (iNSC) – is reflected in the method’s name, SYNCN. The stem cells are used as a patient-specific comparator to GIC to discover pathogenetically relevant mechanisms in GBM and to identify druggable targets, explained study leader Professor Silvia Marino, Director of the Brain Tumour Research Centre of Excellence. ‘We have used this powerful technique to identify changes in the function of genes that occur in GBM that do not entail a change in the genetic code (epigenetics). This has revealed new insights for how GBM develops and identified potential new targets for individualised treatments.’ The research has been funded by the Brain Tumour Research charity in the UK; the researchers published their findings in the journal Nature Communication.

Enabling insightful comparisons

Image credit: Brain Tumour Research Centre of Excellence at Queen Mary University of London

By using a combination of laboratory work and sophisticated analytical computer programmes, the team at Queen Mary has identified significant molecular differences which could be exploited to develop new treatments. The SYNCN approach enables the comparison of normal and malignant cells from the same patient helping to identify genes that play a role in the growth of the tumour. The use of NSC is a key factor in this, since the cells have been identified as a point of origin of at least a proportion of GBM, both in mouse models and in human patients, explained Professor Marino. ‘The strength of our study is to leverage state-of-the-art stem cell technology to derive iNSC from patient’s fibroblasts through in vitro reprogramming, allowing us to compare – for the first time – the epigenetic and transcriptional make-up of GIC with that of patient-matched normal iNSC.’ Previously, this comparison was not feasible, as patient-matched endogenous NSC (eNSC) are not surgically accessible and all epigenetic studies in GBM had so far compared epigenetic changes of GBM cells with each other, or to comparators obtained from fetal brains or an unrelated donor.

GBM is the most common malignant brain tumour in adults, only a quarter of patients survive for more than one year and just 5% live for more than five years. Its aggressive nature allows it to spread extensively into surrounding brain tissue, making complete removal by surgery almost impossible. In addition, GBM is extremely resistant to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, with a strong probability of recurrence after treatment. One of the main challenges in developing effective treatments is that the tumour exhibits significant variation between patients, even displaying variation within a single patient’s tumour.

The complex nature of this particular tumour type means that the standard of care for these patients has not changed in a generation, so this research brings much-needed hope for the future

Silvia Marino

The researchers are confident that SYNCN will offer an important advance in the battle against GBM. Professor Marino said: ‘The availability of matched GIC and iNSC pairs has allowed us to identify crucial epigenetic differences between GBM and iNSC on a patient-specific basis and has provided essential therapeutic contrast to define disease- and patient-intrinsic biomarkers of drug response that are less confounded by germline variation. It could provide a tool for patient-specific drug matching in at least a proportion of GBM patients.’

The preclinical data gathered so far will now need to be validated on larger patient cohorts to assess whether and when this approach could impact patient care. Hugh Adams from Brain Tumour Research said: ‘The complex nature of this particular tumour type means that the standard of care for these patients has not changed in a generation, so this research brings much-needed hope for the future.’

Profile:

Silvia Marino is Professor of Neuropathology at Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London and also Honorary Consultant Neuropathologist at Barts Health NHS Trust. As the Director of the Brain Tumour Research Centre of Excellence, her research focuses on the biology of normal and neoplastic stem cells with her group currently investigating the role of deregulated epigenetic mechanisms in initiation and progression of brain tumours. In her clinical role, she specialises in the neuropathological assessment of neuro-oncological surgical specimens. She is immediate past President of the British Neuro-Oncology Society.

19.05.2022