Article • Cancer imaging

PET/MRI offers significant patient benefits

PET/MRI is offering new imaging opportunities for cancer patients at various points along the care pathway with its ability to assess different biological processes and its increased specificity. The growing clinical role of the hybrid modality was discussed by Professor Vicky Goh during the Sir Godfrey Hounsfield lecture at the British Institute of Radiology virtual annual conference in November.

Report: Mark Nicholls

In her presentation “PET-MR: Integrating the best of both modalities for cancer care”, Professor Goh highlighted the benefits of the combination, but also acknowledged significant challenges.

Professor Goh, who is Chair of Cancer Imaging at King’s College London, opened with a tribute to Sir Godfrey Hounsfield for his Nobel Prize winning role in the development of CT, before outlining how early evidence has established that PET/MRI using the radiotracer 18F-fluoro-deoxy-glucose (FDG) is non-inferior to PET/CT. ‘Over the last two decades there have been significant strides toward personalised cancer care to improve cancer outcome,’ she said. ‘But in order to ensure that patients receive the best treatment at the right time, imaging has had to evolve to meet these needs. The introduction of clinical PET/MRI in 2010 has been another step change in terms of imaging capabilities for personalised cancer care.’

More than the sum of its parts

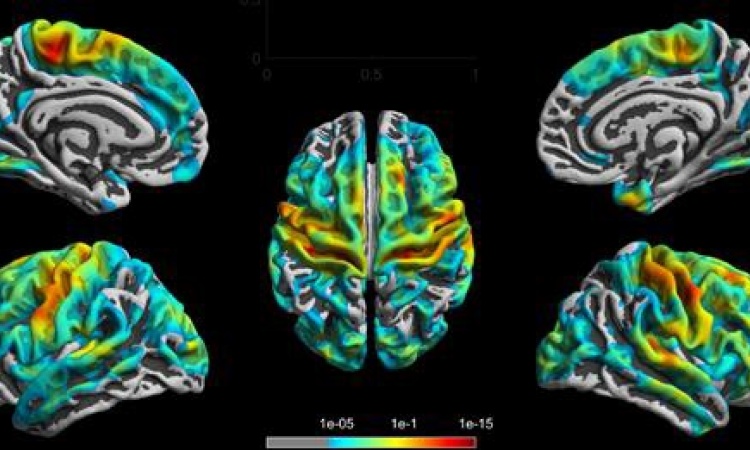

The imaging expert pointed out the key advantages of integrated PET/MRI systems: the high sensitivity and the ability to provide molecular information from PET; combined with the high contrast-to-noise-ratio and spatial anatomical resolution that MR imaging offers. These strengths, she added, make PET/MRI a comprehensive and powerful tool for tumour phenotyping. ‘Furthermore, with PET/MRI, physiological imaging such as vascularisation, oxygenation or diffusion can be easily integrated with anatomical sequences.’

While early concepts of PET/MRI were proposed in the 1990s, it was over a decade before clinical systems were introduced in 2008, with further developments seeing integrated whole-body systems by 2011. However, to achieve this, significant engineering challenges had to be overcome to successfully integrate the two modalities, particularly related to overcoming the impact of each modality on each other. These challenges involved redesign and adjustments to post-processing steps and image reconstruction, including steps for attenuation correction, which is essential for reliable PET quantification. Further factors that had to be considered were motion correction to improve PET quantification, and workflow factors, such as patient positioning.

Benefits in staging and restaging

For suspected recurrence, PET/MRI has been shown to offer greater diagnostic accuracy and diagnostic confidence, particularly for nodal disease

Vicky Goh

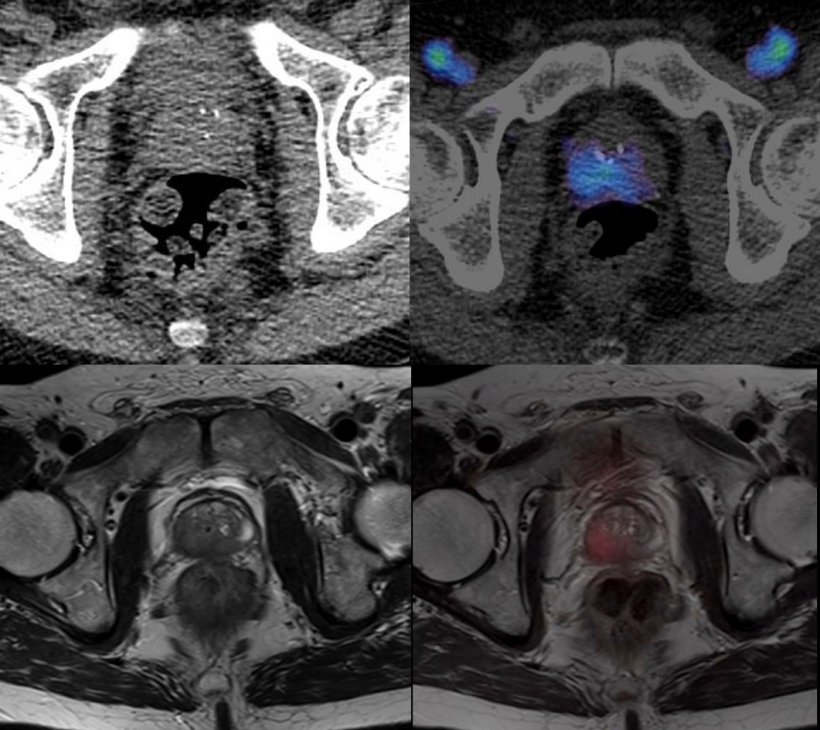

Professor Goh emphasised the clear benefits of lower radiation dose by replacing CT with MRI, particularly in paediatric or young adult populations, where reductions of 50-80% can be achieved. MRI can also outperform CT in localising the PET signal, and the integration of PET and MRI results in increased specificity and improved quantitation. Due to these benefits, PET/MRI has become increasingly established across the clinical pathway in oncology in terms of detection, characterisation, stage and risk stratification, therapy planning and therapy assessment over the last decade. In particular, the use of PET/MRI in detection and characterisation for prostate cancer has been a success story, the expert reported.

The hybrid modality has also proven its worth in staging or restaging for several tumour types, including gynaecological cancers, resulting in greater accuracy and diagnostic confidence. This versatility has been certified in five studies, which assessed the performance of FDG for primary staging and found that PET/MRI enhances local regional staging and therapy planning. Professor Goh added: ‘For suspected recurrence, PET/MRI has been shown to offer greater diagnostic accuracy and diagnostic confidence, particularly for nodal disease.’

Further studies have highlighted the superiority of PET/MRI in detecting, localising and characterising bone and liver metastases. Additionally, the technique can improve patient selection for therapy, such as for neuroendocrine tumours. ‘A number of studies have also shown the added value for PET/MRI in terms of sensitivity for disease and better characterisation of lesions,’ said Professor Goh.

With respect to therapy assessment, she suggested PET/MRI may have a role in clinical trials, while its advantages also apply in some clinical scenarios, for example in the evaluation of myeloma patients undergoing induction chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation. The expert attested to the emerging clinical impact of PET/MRI, referencing two recent prospective studies with different tracers, which demonstrated higher accuracies as well as a change in management due to additional findings. Beyond oncology, PET/MRI has also made its way into the clinical routines in neurology and cardiology, Professor Goh reported.

A more expensive option (that still pays off in the end)

Collaborative working has been the key to development in clinical translation of PET/MRI and remains at the heart of delivering PET/MRI as a clinical imaging tool

Vicky Goh

While PET/MRI may be more expensive than PET/CT, the imaging expert believes that the benefits outweigh the increased costs: higher overall image quality may obviate the need for additional scans and lead to faster management decisions. Regarding the financial impact, treatment costs may even be reduced due to better patient selection for therapies.

Professor Goh concluded: ‘Over the last decade, PET/MRI has demonstrated its viability as a clinical tool with reduced radiation exposures, it offers new insights into the biology of disease, and remains a rich resource of ongoing research for future applications. With increasing personalisation of care, PET/MRI offers the opportunity to transform care delivery for patients and, in particular, to improve patient experience. And there is no doubt that collaborative working has been the key to development in clinical translation of PET/MRI and remains at the heart of delivering PET/MRI as a clinical imaging tool.’

Profile:

Professor Vicky Goh is Head of Department of Cancer Imaging at the School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences of King’s College London, and Honorary Consultant Radiologist at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital. Her translational research focuses on functional and advanced imaging in gastrointestinal, genito-urinary, haematological and lung cancers. She is past president of the European Society of Oncologic Imaging and is currently chairing the Academic Committee at the Royal College of Radiologists.

28.11.2021