Of echoes, triangles and quadrants

Ultrasound of the fatty liver

Medicine is not immune to prejudices. In the past, the ‘fatty liver’ diagnosis was often accompanied by the hasty conclusion that the problem was surely caused by alcohol abuse.

Today, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), receives increasing attention. It is, inter alia, associated with diabetes, detrimental eating habits, adverse reactions to medication or problems in the fat metabolism. About fifty percent of the patients of Professor Günter Layer, Director of the Central Institute of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology at Ludwigshafen Hospital, Germany, show liver fat changes. Prof. Layer knows how to detect them and how to avoid the diagnostic pitfalls.

Whilst fatty liver is quite common, in Professor Layer’s experience it is mostly an incidental finding. Since the centre he heads at Ludwigshafen Hospital focuses on oncology, fatty liver disease is often diagnosed during tumour restaging. ‘Thus we see in many cases the disease is an adverse effect of cancer medication. Today, we are aware that cancer patients are at risk to develop diffuse liver parenchyma diseases, primarily steatohepatitis,’ he explains.

Nevertheless, with regard to metabolic syndrome, an increasing problem in the Western world, poor eating habits, lack of physical exercise and resulting overweight remain the most important risk factors. As steatohepatitis may lead to liver cirrhosis, the professor expects the introduction of targeted screening for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis sooner or later.

Such a screening is possible due to the widespread use of ultrasound. However, as a primary diagnostic tool, ultrasound yields very inconsistent results. Study conditions play a major role, Prof. Layer points out. In obese patients sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound decreases by fifty percent while in normal-weight patients accuracy is somewhere between 80 and 90 percent, which is pretty close to the current gold standard – biopsy.

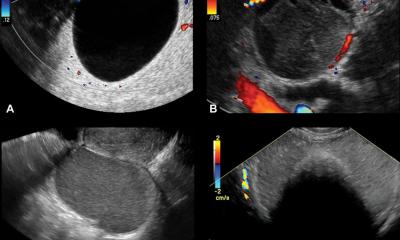

A typical feature of the fatty liver is increased echogenicity. However, dense subcutaneous fatty tissue, which attenuates penetration of the ultrasound beam, make an accurate diagnosis much more difficult.

MRI is a second imaging method to confirm or rule out fatty liver. ‘While liver MRI does provide precise quantitative data, in most radiology offices or clinics this procedure is not part of the standard study portfolio,’ Prof. Layer explains, adding that MRI ‘requires special fat quantification techniques, be it special sequences or spectroscopy, which are being offered by very few facilities.’

In ultrasound, operator experience can highly impact on the evaluation of fatty liver or liver fibrosis because these diffuse tissue changes are much more difficult to delineate and quantify than focal liver lesions such as tumours or metastases. ‘Moreover, the fatty regions can be distributed very unevenly throughout the liver, which increases the risk of mistaking fat for tumours or vice versa. Therefore,’ he advises, ‘it’s important to be familiar with the typical distribution patterns of steatoses and non-steatotic conditions.’

Focal low-grade fat accumulations that define liver steatosis frequently present as triangular changes near the gall bladder and as square-shaped changes in liver segment IV near the falciform ligament. The different degrees of fatty degeneration are believed to be caused by local changes in organ blood supply. How much experience precisely does a sonographer need to be sufficiently confident in diagnosing fatty liver? Professor Layer: ‘Speaking from my own experience I’d say that you need to perform such abdominal exams several times a day for about a year to gather enough experience and be really confident.’

PROFILE:

Following medical studies at the universities of Heidelberg and Zurich, Professor Günter Layer trained as a radiologist in Professor van Kaick’s team at the German Cancer Research Centre and as assistant to Professor Reiser in Bonn. Since 2001 he has directed the Central Institute for Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology at Klinikum Ludwigshafen. The professor is, inter alia, a Member of the Board of the German Roentgen Society (DRG) and founder as well as current head of the Chefarztforum at DRG. His work focuses on abdominal diagnostics and oncological diagnostics and therapy.

Based on an article in RöKo HEUTE 2013, the official publication of the German Radiology Congress

30.07.2013