News • Breakthrough against C. diff

New Clostridioides difficile vaccine on the horizon

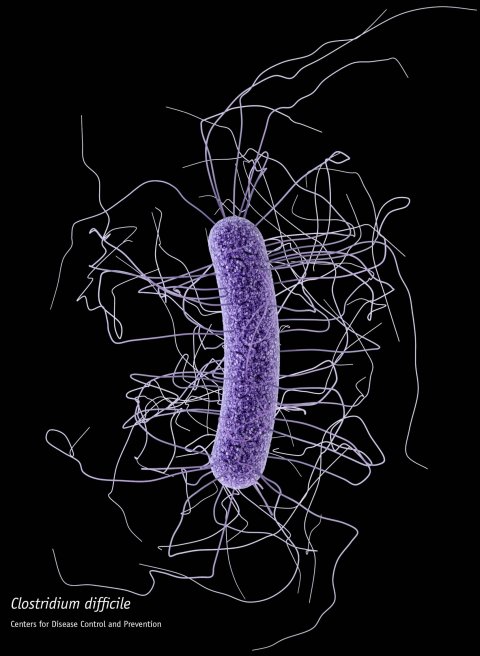

Researchers at the University of Exeter first identified a gene in the 'hospital bug' Clostridioides difficile responsible for producing a protein that aids in binding the bacteria to the gut of its victims.

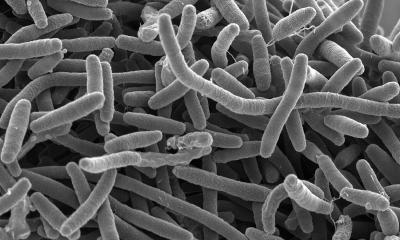

Image source: Norbert Bannert, Kazimierz Madela/RKI

In collaboration with researchers at Paris-SUD University, they then showed that mice vaccinated with this protein generated specific antibodies to the protein – and that C. diff that did not produce this protein were less able to attach to the gut. C. diff bacteria must bind to the gut to produce the toxin that causes illness, and the Exeter team are hopeful that vaccination against attachment will be effective in humans. No C. diff vaccine is currently in widespread use. Some toxin-based vaccines are currently in clinical trials, but the Exeter research offers a promising new approach.

The researchers published their findings in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Image source: CDC/James Archer

C. diff infections, which commonly occur in people who have recently taken antibiotics, can cause severe illness and results in thousands of deaths each year, especially among the elderly and other vulnerable groups. “Infection by C. diff often occurs when the natural gut bacteria are disrupted by antibiotics,” said Dr Stephen Michell, of the University of Exeter. “With other bacteria missing, C. diff can attach to the gut and release a toxin that causes symptoms including diarrhoea. We identified a gene – CD0873 – that generates a protein that helps C. diff bind to the gut. This binding is thought to be key for C. diff infections, so if we can prevent adhesion of bacteria then there’s a real possibility of preventing this disease.”

The researchers immunised mice with the CD0873 protein in isolation (not as part of a C. diff bacterium) and found a “strong” immune response. When subsequently exposed to C. diff, these immunised mice were unaffected while non-immunised mice fell ill and lost about 10 percent of their body weight on average.

The research began as a collaboration between the University of Exeter, Novartis and the University of Nottingham, and this latest collaborative study involved the University of Bath and University Paris-Sud. Both the universities of Bath and Exeter are part of the GW4 Alliance, a collaborative research alliance of research-intensive and innovative universities in the South West and Wales. Scientists at University Paris-Sud conducted the experiments that showed that mice develop antibodies when immunised with the CD0873 protein. The Bath researchers mapped the 3D molecular structure of CD0873 at high resolution using the high-brightness X-ray beam at the UK’s state-of-the-art facility, Diamond Light Source at Didcot in Oxfordshire providing more information on its function.

Our current treatments rely on using more antibiotics, and we need to move away from that approach as antibiotics are one of the main causes of the C. diff problem in the first place

Ray Sheridan

A study published in 2015 said C diff caused almost half a million infections in the US in a year, directly leading to 15,000 deaths. Whilst several C. diff toxin-targeted vaccines are currently in clinical trials, in 2017, pharmaceutical company Sanofi scrapped its efforts to find a toxin-based C. diff vaccine after many years, citing a low probability of success. This alternative, adhesion-targeting vaccine identified by this important research may be a key new approach to disease control.

Dr Ray Sheridan, a consultant physician at the Royal Devon & Exeter Hospital, said: “A vaccine that stops the C. diff sticking to the gut wall and so stops it making the gut its new home would then stop the bug being able to cause diarrhoea or infection. This would need to go through clinical trials but if it worked it would potentially prevent C. diff infection altogether. Our current treatments rely on using more antibiotics, and we need to move away from that approach as antibiotics are one of the main causes of the C. diff problem in the first place by interfering with natural gut flora of bacteria.”

Source: University of Exeter

28.10.2019