Photograph: Iliana Kyriaki Kerzeli

News • Tumour development research

New bladder cancer model could lead to better treatment

Uppsala University scientists have designed a new mouse model that facilitates study of factors contributing to the progression of human bladder cancer and of immune-system activation when the tumour is growing.

Using this model, they have been able to study how proteins change before, while and after a tumour develops in the bladder wall. The study has now been published in the scientific journal PLOS ONE.

Photo: Mikael Wallerstedt

“The model was designed both to contain specific oncogenes, as they’re called — mutations that can drive tumour growth — and to show a high incidence of harmful mutations, which we often see in people who get bladder cancer. These harmful mutations arise because of smoking, for instance, which is the single biggest risk factor for bladder cancer in the West. In that way, our model imitates how this form of cancer develops in humans,” explains Sara Mangsbo, principle investigator and senior lecturer at the Department of Pharmaceutical Biosciences at Uppsala University.

The main challenges in creating the mouse model were, first, to produce an organism with an immune system that functions like the human one and, second, to cause the tumour to grow in the right site and for the same reasons as in us. Previous studies and models have often used female mice as mouse models for bladder cancer, which does not fully reflect what the disease is like in humans, where the cancer is three times as common in men as in women. However, women often have a more aggressive cancer at the time of diagnosis. In the new model, both sexes have been investigated and it can therefore be used to study how tumours develop in females and males respectively, and how both respond to various treatments.

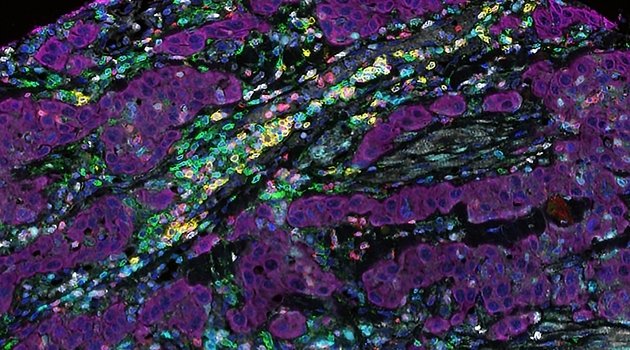

The scientists have now used the model to take a closer look, in blood and urine, at the proteomic profile (secreted substances from the tumour/immune cell area) when the tumour arise, grow and spread. The investigations included examining more than 90 proteins to find out how these change in the course of tumour development and after the disease has infiltrated the muscle layer), called muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

We hope that, in the future, [the model] will help to improve our knowledge of how to design treatment strategies specifically adapted for men and women

Sara Mangsbo

How the gene expression in the tumour changed from when it was confined to only one site to when it had infiltrated the tumour was studied through “single-cell sequencing”. Thus, the researchers were able to get an idea of which cells were appearing and which disappearing, how cancer cells and surrounding tissue were interacting and which types of immune cell were being activated.

The scientists noted a distinct gender difference both in the type of bladder cancer that developed in the early stage of the disease, but also that the sexes responded differently to immunotherapy, a form of treatment that activates the immune system to fight tumours. “In the next phase of the project, the model can give us a better understanding of the types of immune cell that infiltrate the tumours. And we hope that, in the future, it will help to improve our knowledge of how to design treatment strategies specifically adapted for men and women. For this to become a reality, studies must also be linked to analyses of clinical material from biobanks,” Mangsbo says.

Source: Uppsala University

08.07.2021