News • Systemic cell rewiring

How midkine helps tumours evade immunotherapy

Cutaneous melanoma, the most aggressive form of skin cancer, is characterised by its accumulation of a large number of mutations.

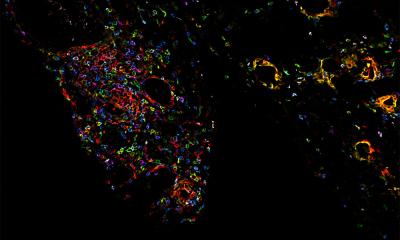

Image source: Pilar Gil / CNIO

Although some of these alterations should be recognised as a threat by our defences, melanomas often escape immune system surveillance. As a result, more than half of patients do not generally respond to current immunotherapies. Understanding and avoiding this phenomenon is one of the greatest challenges in oncology today.

Now, a study by the Melanoma Group, led by Marisol Soengas, at the National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) has discovered a mechanism by which melanomas and other aggressive tumours prevent the immune system from recognising and attacking them, as one might expect. The study also helps to understand why when melanoma spreads to other organs, leading to metastases, it often develops resistance to conventional immunotherapy.

The research paper is published in Nature Cancer, with Xavier Catena –currently at the University of Lund (Sweden)– as the first author. After conducting studies on cells, mice and more than 150 patient databases, the team has found that melanoma cells secrete a protein, called Midkine, which reduces the number of a type of cell specialised in tumour recognition, dendritic cells.

In addition, Midkine reprogrammes dendritic cells to change their function so that they promote tumour development. “In this research, we found that Midkine acts as a shield and accelerator at the same time: it prevents the recognition and elimination of tumour cells, and also actively facilitates the progression and spread of malignant cells,” Soengas explains.

Dendritic cells normally act as sentinels organized in defence patrols which identify foreign molecules in pathogens such as viruses and bacteria, and also in tumours. They then present this information to other defensive cells, cytotoxic T lymphocytes, for them to kill the malignant cells. This article now demonstrates that in melanomas, Midkine reduces the number of dendritic cells and changes their functioning. “The most important thing about this work is that we have understood how, through Midkine, melanoma not only shuts down or cools the immune system, but also perverts it in its favour, actively contributing to its spread,” concludes the researcher. “It does this from a very early phase, and also on the scale of the whole organism. This complicates the development of new therapies.”

Image source: Amparo Garrido / CNIO

After discovering how Midkine blocks the immune system, the research focused on analysing the impact on treatments. The CNIO group demonstrates in animal models that preventing the action of Midkine improves the efficacy of vaccines that target dendritic cells. In addition, preventing Midkine from acting also facilitates the therapeutic action of one of the most common forms of immunotherapy, the so-called immune checkpoint inhibitors.

CNIO researchers also analysed data from large cohorts of patients and found a gene signature associated with Midkine in dendritic cells that correlates with worse prognosis. This finding transcends melanoma, as similar effects were observed in cancers of the lung, breast, endometrium, adrenal gland and mesothelioma, among others. “Our results suggest that inhibition of the Midkine protein could reactivate dendritic cells and improve therapies against different aggressive tumour types,” Soengas adds. These findings add new information to previous studies by the CNIO Melanoma Group, which had already shown that the Midkine protein can promote melanoma metastasis and alter the function of other components of the immune system.

Source: Spanish National Cancer Research Centre

02.04.2025