Oophorectomy

Leading expert takes stand against prophylactic oophorectomy

“I am very concerned about the impact that Angelina Jolie has on the media,” Walter Rocca, professor of epidemiology and neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, stated. He wasn’t hinting to Jolie’s acting choices or waifish silhouette, but to the confusion surrounding her decision to remove her ovaries to prevent ovarian cancer.

By Mélisande Rouger

“I am very concerned about the impact that Angelina Jolie has on the media,” Walter Rocca, professor of epidemiology and neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, stated. He wasn’t hinting to Jolie’s acting choices or silhouette, but to the confusion surrounding her recent decision to remove her ovaries to prevent ovarian cancer.

The actress went public in the New York Times about her surgery in March, following another public disclosure about her mastectomy in 2013. Many practicing gynaecologists are now being approached at the Mayo Clinic and elsewhere by panicking women asking about the benefits of having their ovaries removed in order to live longer.

“There has been a lot of misunderstanding around her statement. Ms. Jolie is a carrier of a rare genetic variant called BRCA1, which prompted her decision. A lot of women thought they had to do the same to prevent ovarian cancer and to continue to be with their kids, which is absolutely wrong. 99.5% of women do not have this genetic variant and have nothing to do with her situation,” he insisted.

BRCA1, a very rare gene variant, is linked to a 60-70% risk of developing breast cancer and to a 50% risk of ovarian cancer. Women carrying BRCA1 represent less than 1% of the population, and carriers of BRCA2, another genetic variant linked with cancer incidence, are even less frequent.

Rocca emphatically made the case against prophylactic oophorectomy, “one of the most incredible controversies in the practice of gynaecology.” Taking a historical approach, he quoted the work of William H. Parker, who opened the debate over the harms and benefits of the procedure in 2005. After a decade of discussion, opinions are still diverging.

“Some people continue to say that prophylactic oophorectomy is a good idea, and that there is uncertainty about the good and the bad of the procedure. As a result of the presumed uncertainty, women and their doctors can make the decision about whether or not to remove the ovaries. By contrast, I think that the evidence is adequate to suggest that oophorectomy is not justified in the majority of women who do not have a special genetic risk, and should therefore not be offered as a solution,” he said.

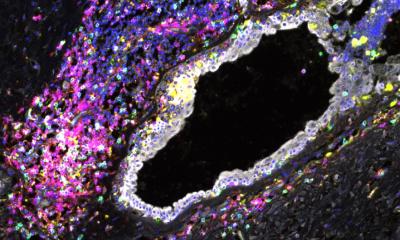

Removing the ovaries reduces the risk of ovarian and breast cancer significantly, but the price is an increased overall mortality of 28%, according to data in several scientific publications and summarized in an editorial in Maturitas of 2012. The risk of coronary heart disease, the leading cause of death in women, augments by 33%; so does the risk of stroke, lung cancer, and osteoporosis and bone fractures. Mental health is also affected, and the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia increase by 60%, Parkinson’s disease by 80% and psychiatric symptoms up to 130%. The risk of impaired sexual function increases by up to 110%.

The deleterious effects of oophorectomy take up to 20 to 30 years to emerge. This delay is generating a lot of errors, Rocca believes. “Until 2005 nobody had any question about the long-term safety of oophorectomy, because nobody had seen anything bad happening to women after the surgery. These effects have never been seen in clinical series and surgical experiences, and it’s also why clinical trials cannot be done on oophorectomy,” he said.

Oophorectomy appears to also be responsible for early ageing, a recent comparative study at the Mayo Clinic showed. Out of approximately 2,000 women who underwent oophorectomy between 1998 and 2007, 96 died in 14 years – the time of the study follow-up. Out of approximately 2,000 other women of the same age without any surgery, only 53 died.

The oophorectomy group also had higher morbidity in conditions regarded as markers for accelerated ageing such as anxiety, depression, substance use, dementia, schizophrenia, somatic hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, diabetes, arthritis, osteoporosis, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

“We interpret these data as suggesting that women who have their ovaries removed precipitate into a state of accelerated ageing, because oestrogen is a general modulator of metabolism and genetic expression in many tissues and organs of the body. Women who undergo oophorectomy present with more conditions at the time of the surgery, and they manifest accelerated ageing after the surgery, especially if they have oophorectomy before 45,” he said.

Only women who carry a BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic variant, or some other rare genetic syndromes, should consider bilateral oophorectomy before 50, but they must be informed of what may happen after surgery, he argued.

If oophorectomy is performed, women should consider oestrogen therapy at least up to age 51, unless there is a clear counter indication. Oestrogen intake can reduce mortality, coronary heart disease stroke, cognitive impairment and dementia. However, removing the ovaries eliminates the production of other hormones such as progesterone, testosterone, and other steroids that can be converted into oestrogen. Women are thus still at risk of anxiety, depression, Parkinsonism and glaucoma.

“The simple logic that ovaries in, ovaries out is an oestrogen problem is a very incomplete notion,” he summed up.

Oophorectomy after age 50 up to age 65 may still be deleterious; however, the risk-to-benefit ratio is less clear and the data are less convincing.

PROFILE:

Walter A. Rocca is Professor of Epidemiology and Neurology at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minnesota. He previously worked for the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in Bethesda, Maryland, and for several European institutions. His main research interests include the identification of genetic and environmental risk factors for Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer's disease, and vascular dementia. Dr Rocca received his M.D. from the University of Padua, in Padua, Italy, his M.P.H. from the Johns Hopkins University, School of Hygiene and Public Health, in Baltimore, Maryland, and completed postdoctoral fellowships at the Johns Hopkins University and at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Rocca served on several expert panels for the National Institutes of Health and for other institutions nationally and internationally. He has over 160 publications to his name.

15.06.2015