Article • Blood transfusions

Donor organs become immunologically invisible

The safety of blood transfusions is questioned again and again by the mass media. Sometimes ‘bad’ blood causes infections; sometimes a transfusion leads to cancer years later. The fact is that transfer blood is subjected to the highest safety standards – there are very clear statutory regulations.

Report: Anja Behringer

Nonetheless, there will be shortages of ‘life’s fluid’ because, given increasing longevity, the proportion of older patients that need blood is significantly higher. At the same time a willingness to donate blood is declining: the share of whole blood donors among the general population dropped from 3.3% to 2.8% between 2008 and 2016. Moreover, the proportion of younger people among the total population is declining and, starting at 68, a physician must decide whether a blood donation is possible. Whereby older people are those who will depend on transfusions in the future. The future need for blood reserves can hardly be predicted. Medical progress will reduce the demand for blood products by means of refined operative techniques and new medicines in cancer therapy, but the demographic development will lead to an increase in illnesses requiring blood transfusion, such as cancers and thus increase the need for blood supplies.

Recommended article

Article • Organs and qualified surgeons drop

Will transplant medicine have a future in Germany?

‘Do we want transplant medicine? And if yes, what are we prepared to change in public policy, society and medicine?’ This question characterises the current situation within this medical discipline. Since the 2011 transplant scandal, there has been a steady decline in organ donations according to the German Foundation for Organ Donation (DSO). Although there were some 1,200 transplant donors…

Donor blood safety

Blood transfusions are safer today than ever

Holger Hennig

At the annual meeting of the German Society for Transfusion Medicine and Immune Haematology, in Lübeck, all aspects have been discussed. Blood donation can save lives. However, a potential risk is that pathogens can be transmitted. To keep this risk as low as possible, blood products are tested or treated for the most important pathogens, so that possible viruses or bacteria can be deactivated. An infection due to a transfusion is extremely unlikely. ‘Blood transfusions are safer today than ever,’ confirmed Professor Holger Hennig, deputy director at the Institute for Transfusion Medicine of the University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein in Lübeck and president of the DGTI congress.

In Germany today, especially due to the molecular biological testing applied, it is extremely unlikely that a dangerous viral infection can be transmitted through blood products. Thus the risk that human immune deficiency virus (HIV) is transmitted through a blood transfusion is less than 1: 25 million. The probability of infection with hepatitis C viruses (HVC) through foreign blood is even less than 1:75 million and only around one in eight million blood units is contaminated by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). ‘This number will probably decline even more in the coming years,’ Hennig explained. ‘Since the 1990s, the vaccine calendar calls for immunisation against HBV already in childhood.’

Recommended article

Article • Patient blood management

Blood transfusions: Patient groups should be precisely defined

Although blood transfusion today is a well-established and safe procedure, the medical science community has not yet arrived at a consensus regarding appropriate patient blood management (PBM) methods. ‘Many PBM approaches have not yet been scientifically validated; consequently over- as well as under-transfusion might be associated with adverse events and complications for the patient,’…

However, the introduction of ever-newer tests generally collides with financial and organisational barriers—already the introduction of the Hepatitis-E-Virus (HEV) tests, since 2013, when individual cases of virus transmission through blood transfusion were registered, is keenly debated by experts. Therefore transfusion medicine is facing a change in thinking away from specific testing for individual pathogens and towards the general deactivation of pathogens in blood products. Specific tests are also avoided when dealing with exotic pathogens that can enter the country with travellers. Instead those willing to donate, who return from a region with a high infection risk for e.g. malaria or Zika, the West Nile or MERS virus must maintain a ‘quarantine’ of four to six weeks before they can donate blood again. In this way the transmission of possible infections is prevented without expensive tests.

Furthermore, the guidelines of the German Federal Physicians Association very strictly govern the use of blood in therapies with blood components. Today’s patient blood management also involves taking numerous other measures to prevent the need for transfusions. Hence potential anaemia is already treated prior to surgery. During the operation every effort is made to re-use the patient’s blood as much as possible.

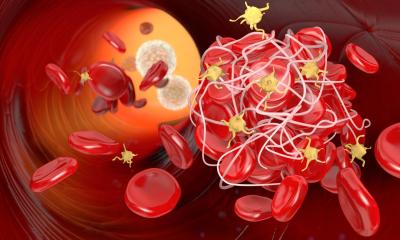

'Invisible' organs against rejection

Patients need lots of blood, especially in connection with organ transplantations. This means that the risk of organ rejection must be kept as low as possible. Therefore, Professor Rainer Blasczyk of the Institute for Transfusion Medicine of the Medical College Hanover works with his team on a method of organ engineering, which leads to organs that are invisible to the recipient’s immune system. In this future scenario, currently being tested on large animals, avoidance of rejection is to significantly increase the number of available organs by making re-transplantation less frequent. Until now the basic idea for avoiding a rejection has always been to modify the recipient’s immune system to attain an immunological blindness towards the transplanted organ, usually at the expense of life-long immunosuppression. Now the research objective has been completely reversed – to make the donor organ immunologically invisible.

Profile:

In 1998, a year after physician Rainer Blasczyk had completed his aggregate in transfusion medicine at the Charité, Humboldt-University Berlin, he was appointed university professor and director of the Institute for Transfusion Medicine at the Medical College in Hanover. In 2009, he became a member of the Scientific Committee of the European Federation for Immunogenetics and, from 2014 he has been a member of the management board of the Integrierten Forschungs- und Behandlungszentrums Transplantation (IFB-Tx) of the MHH, which receives funding from the Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF). For the past four years Blasczyk has been active in the ‘Blood’ working group at the Robert Koch Institute, German Federal Health Ministry.

13.04.2019