News • Skin cancer research

Aggressive melanoma: cells at tumour's edge are key to cancer spread

Research led by Barts Cancer Institute (BCI), Queen Mary University of London, has revealed novel insights into the mechanisms employed by melanoma cells to form tumours at secondary sites around the body.

The findings from the study, published in Nature Communications, may help to identify new targets to inhibit melanoma spread and guide treatment decisions in the clinic.

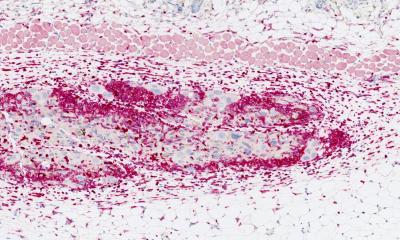

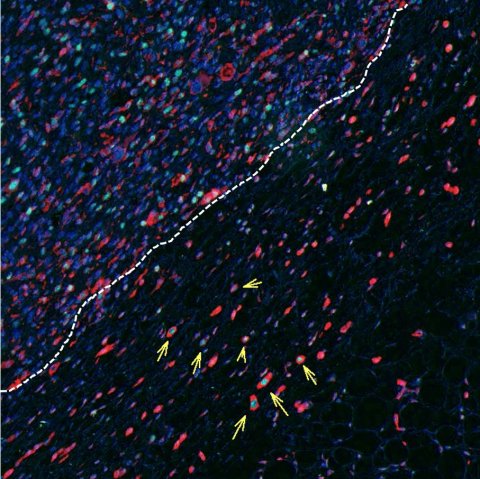

Image source: Rodriguez-Hernandez et al., Nature Communications 2020 (CC BY 4.0)

Melanoma is an aggressive type of skin cancer, and melanoma cells disseminate easily through the body even at early stages of the disease. The spread of cancer from one site in the body to another in a process called metastasis is the leading cause of cancer mortality. In order for cancer to metastasise, cancer cells must break off from the primary tumour, travel through the bloodstream or lymph system, settle in a new site within the body and grow into a new tumour.

The findings of this study revealed that there is a highly invasive subset of melanoma cells located around the edge of the tumour, called ‘rounded-amoeboid’ cells, that not only disseminate through the body very efficiently, but are also very successful at forming new tumours. Dr Irene Rodriguez Hernandez, first author of the study said: “An important observation of our study was that aggressive melanoma cells were not only very invasive but were good at dividing. Therefore, such melanoma cells were capable of growing new tumours both in the skin and at a distant site such as the lung. Our work sheds some light on the ability of melanomas to form metastases very early in the progression of the disease.”

By using melanoma cell lines and preclinical models, the team found that melanoma cells can initiate tumours at new sites via a powerful signalling cascade. Melanoma cells produce a molecule called Wnt11, which binds to a second molecule on the surface of the cancer cells called FZD7. Once bound, these molecules activate a protein called DAAM1, which in turn controls a protein called Rho A - a master regulator of cancer invasion. This set of events allows melanoma cells to invade surrounding tissue and makes them more capable of growing new tumours when they reach new sites within the body.

Interestingly, these signalling molecules are also important during human development from the embryo. Melanoma originates from the pigment-producing cells within the skin called melanocytes, which are formed from a set of cells called neural crest cells. Neural crest cells are highly migratory; they move around to different regions of the body to give rise to many different cell types during human development. Professor Victoria Sanz-Moreno from BCI’s Centre for Tumour Microenvironment, who led the study, said: “The molecules that melanoma cells use to become invasive and to grow are important for neural crest functions during human development. We have uncovered a mechanism by which cancer cells hijack this developmental programme to become aggressive. It is a bit like melanoma has a ‘cellular memory’ to revert to that neural crest state.”

Implications for melanoma treatment

To determine if their laboratory findings were representative of melanoma in the clinic, the team analysed samples from primary tumours in melanoma patients. Their analyses revealed that the edges of melanoma tumours were enriched with rounded-amoeboid cells that expressed the signalling molecules that promote both growth and invasion. The research was performed in collaboration with researchers from the Francis Crick Institute and King’s College London, and funded by Cancer Research UK, Barts Charity, Fundacion Alfonso Martin Escudero and Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions.

Metastatic cancer claims the lives of the majority of cancer patients, thus therapeutic interventions that stop the spread of cancer are urgently required. The findings from this study have important implications for surgical intervention. As the cells that initiate melanoma spread are located at the edges of tumours, it is important that these dangerous cells are removed during surgery by leaving a wide surgical margin of cancer-free tissue when the tumour is excised. This study also identifies key players in metastatic melanoma that may be able to be targeted with drugs to stop cancer cell dissemination and the formation of new tumours.

The team will now continue to define a panel of markers to identify these very dangerous amoeboid invasive cancer cells, and will try to isolate them from blood to determine their prognostic potential. Furthermore, they are working on other solid tumours to see if their observations expand to other cancer types.

Source: Cancer Research UK Barts Centre

21.10.2020