Article • Time for a revolution?

About the end of medicine, as we know it

Currently many researchers and experts assume that the next great socio-economic revolution will include a completely new definition of health and how we define illnesses and therapies. “Our health system today can no longer be sustained in its existing form. It has become too expensive and too ineffective,” Professor Harald Schmidt, head of the Department of Pharmacology and Personalised Medicine, Faculty for Health, Medicine and Life Sciences at the University of Maastricht, is convinced.

Report: Sascha Keutel

Professor Schmidt, you predict the end of medicine, as we know it. How do you justify this thesis?

A fundamental problem is that our definition of illness is based on organ localisation or individual symptoms. All medicine, as we teach it, in the way we train specialists, the way our clinics are structured, is divided according to organs. There is a specialist physician and clinic for every organ. However, illnesses do not function that way, rather we experience disruptions in the signal systems in our cells—put more exactly, in certain hotspots that are disturbed and cause symptoms. In most cases these signal disruptions occur in more than one organ and produce different symptoms. Thanks to the organ-based division, we do not see that though. And thus there are hardly any systematic or holistic approaches to medicine.

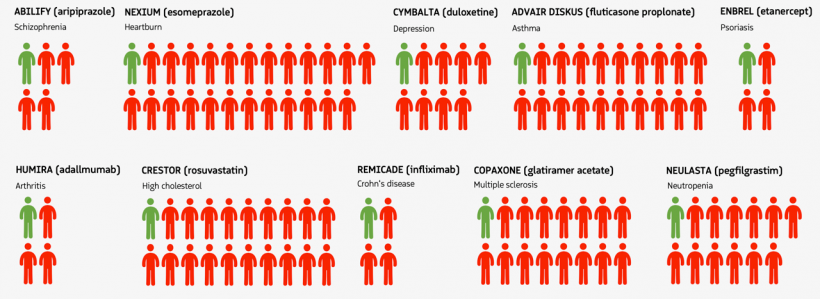

The pharmaceutical industry is also contributing to the end of medicine, as we know it, doomed in its current form. In the list of the world’s ten largest companies there is not a single pharmaceutical company any more. That is somehow logical since why should we be forever discovering new medicines? One reason, after 100 years of pharmaceutical industry why we are still researching for new medicines is the lack of precise illness definitions and the chronic treatment of symptoms instead of healing. To date we know the molecular causes of very few illnesses and therefore cannot treat them.

Source: adapted from Scannell et al. (2012) Nat Rev Drug Discov 11(3):191-200

In your opinion, what has to change?

Medical education will have to change along with hospital structures. Physicians will have to work in interdisciplinary teams more often, together with bioinformatics specialists and system physicians. Actually, the days when the medical specialist treats a patient based on his personal current knowledge are already over now.

A research phase will precede these changes. But it is clear to see that such a medicine will lead to significantly more interdisciplinary hospital structures. Thus the first clinics have already introduced immune disease boards. In these boards illnesses like psoriasis, asthma, colitis or rheumatoid arthritis are treated in the team and working like the familiar tumour boards for oncological issues. Even experts agree that these disease designations are obsolete. These are essentially immune system diseases that have to be defined molecularly and not by clinical morphological means.

Only those pharmaceutical enterprises will survive that heal rather than treat

Harald Schmidt

We also have to bid farewell to classical pathology, currently exhausted by histology and the detailed description of cell changes. More than anything we need a molecular pathology that leads to molecular disease definitions and thus permits precise diagnosis and therapy. In order to attain this we have to work more in terms of systems and more holistically.

Once we have penetrated deeply enough to identify the disease mechanisms, then we can apply a precisely suited medication – possibly one that has already been approved. In the not too distant future, there will be at least one appropriate medication for all the disease mechanisms so defined, the number of which will be between 160 and 200. Thus a researching and developing pharmaceutical industry is obsolete; only manufacturers and distributors will still be needed. Only those pharmaceutical enterprises will survive that heal rather than treat.

First steps have been taken in this direction. In 2018, the FDA approved tumour medications that are no longer approved for the treatment of an organ tumour but for an oncological mechanism. That means they are approved for the specific mechanism, regardless of where the tumour is found. That is a small turning point for medication therapy.

What effects will technologies such as artificial intelligence or big data have on the health system?

Despite necessary changes, the treatment cycle initially will naturally stay the same: as a rule the patient with organ-based symptoms will look for a physician, only his diagnosis will be strongly supported by artificial intelligence. Perhaps AI will propose to the physician additional measurement parameters, digital imaging or genetic examinations and thus determines a molecular illness diagnosis. Then just like today it will be the task of the medical team to support the patient in choosing the optimum therapy for him.

The physician is no longer lone master of diagnosis – he cannot be anymore. The networked data analysis that is necessary to analyse big data will be possible everywhere. Nonetheless there will still be precise ad hoc diagnoses and manual therapies, such as the surgical specialties. However there will be big changes in the field of chronic illnesses.

Recommended article

Article • Future of radiology

'Radiologists who do not use AI will be replaced by those who do'

Recent developments in artificial intelligence (AI) created a veritable hype. However, that initial awe was increasingly mixed with apprehension about the potential effects of AI on healthcare. In radiology, bleak dystopias are conjured up with AI replacing the human radiologist. A scenario that Dr Felix Nensa considers premature, to say the least.

What about treatment errors, if the AI proposes the wrong treatment?

Currently the most common cause of death is physician’s error – we already have the problem. The computer does not administer therapy; AI proposes a diagnosis with a probability of x and the therapy appropriate to it. The decision as to which way to go is reserved to the medical team, the patients and their priorities.

Profile:

Professor Harald Schmidt is a physician and chemist and pharmacist and chair of the Department of pharmacology and personalised medicine, Faculty for Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, University of Maastricht. As advanced investigator of the European Research Council (ERC) he leads various research programmes, among them also a Proof-of-Concept study on strokes; the COST Action OpenMultiMed on system medicine and the Horizon 2020 programme REPO-TRIAL. Schmidt was co-founder and managing director of Vasopharm GmbH, is co-publisher of the journal Systems Medicine and has written more than 200 refereed international publications, summary articles and books.

Event announcement:

ETIM 2019 - Artificial Intelligence and Smart Hospital Summit

Saturday, 23 February 2019, 3:55-4:30 pm

The end of medicine as we know it?

Professor Harald Schmidt (Maastricht)

06.02.2019