Article • WB-MRI vs. prostate cancer

Whole-body MRI improves disease evaluation

Whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (WB-MRI) is championed as offering significant benefits, such as improving disease evaluation for prostate cancer patients.

Report: Mark Nicholls

During an intense session in genito-urinary cancer at the ECR 2019, three key speakers focused on the advantages over conventional imaging modalities – including bone and CT scans – as well as discussing new PET (Positron Emission Tomography) tracers, and raising concerns about the relevance of the current Prostate Cancer Working Group (PCWG) guidelines within the evolving diagnosis and treatment landscape.

The ‘Whole body imaging in metastatic urinary tract and prostate cancer’ session was chaired by Professor Anwar Padhani, consultant clinical radiologist at Mount Vernon Cancer Centre in London, who initially posed questions about which techniques to use and when. He suggested that conventional imaging can lead to poor confidence for assigning clinical states and assessing therapy benefits for bone disease. Limited imaging tools cannot accurately predict metastatic disease presence and extent, or are unable to identify who is not benefiting early after starting treatment; they also are limited in depicting heterogeneity of biologic behaviour of bone disease, Padhani pointed out.

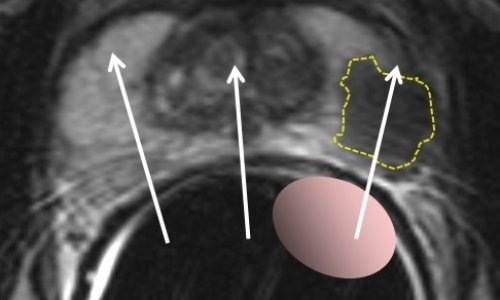

Professor Frederic Lecouvet, from the Catholic University of Louvain in Brussels, Belgium, explained that metastases from prostate cancer mainly involve the skeleton and lymph nodes, and that two ‘modern imaging modalities’, WB-MRI and PET, are the current best options, with significant advantages from WB-MRI. ‘Whole body MRI – covering the body ‘from eyes-to-thighs’ – can detect metastatic infiltration of the bone marrow; it also plays a role in detecting lymph node infiltration and, most importantly, it can assess response to treatment,’ Lecouvet told delegates.

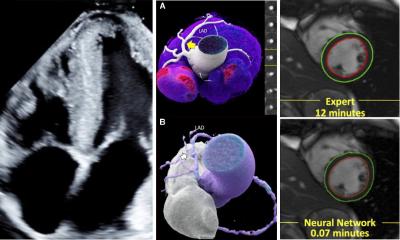

He compared WB-MRI with PSMA PET-CT in several examples. WB-MRI examinations should include both T1 and STIR ‘anatomical’ sequences, and ‘functional’ diffusion sequences, providing a PET-like image. ‘The combination details the anatomy and characterises the lesions, yet offers functional information on tissue viability and response to treatment. ‘It’s an intrinsically hybrid technique,’ Lecouvet pointed out. He demonstrated that WB-MRI provides an all organ approach and looks beyond the skeleton to the nodes, liver and lung. From there, its indications are extending beyond prostate cancer to renal, testicular, ovarian, breast, lung cancers, and to haematological malignancies.

Lecouvet also outlined the MET-RADS-P reporting template for prostate cancer. The recommendations are designed to promote standardisation in the acquisition, interpretation, and reporting of WB-MRI prostate cancer. Used at different time points during the disease, it allows the evaluation of patients for response to treatment of the bone, node and visceral lesions that are recorded and followed-up using morphological and quantitative information. Dr Nina Tunariu, consultant radiologist at the Royal Marsden Hospital, London, concentrated on ‘WB-MRI Response and Assessment’ and told the congress session that imaging approaches to prostate cancer had changed significantly over the last decade, primarily driven by patient and clinician expectations. She said bone scans are still requested by clinicians but are no longer necessarily an essential part of the process because they offered late detection and poor accuracy.

Another issue, she said, is that active disease depends on the image you use. ‘Prostate cancer is very heterogenous, so there will not be a perfect single technique,’ she pointed out. ‘Diffusion MRI as part of WB-MRI will help you see more lesions when other imaging techniques are letting you down, while WB-MRI can show a response to treatment whereas CT and a bone scan will not tell how a patient has responded. WB-MRI will inform about response and progression early and detail early disease and relapse - it is indeed a very comprehensive technique.’

Early identification of treatment failure, she added, not only spares futile treatment but also potential toxicity and reduces the cost of ineffective treatments as well as decreases the time to the next line of potentially effective treatment.

In conclusion, Tunariu pointed to the imaging response to prostate cancer on WB-MRI: it offers early detection of response, especially in bone lesions; early detection of local relapse; accurate assessment of visceral metastases and of any complications.

Dr Irene Burger from the Department of Nuclear Medicine at University Hospital Zürich, looked at PET and PET/MRI in prostate cancer, and the role of PSMA in prostate cancer. She pointed out that PSMA is ‘not a prostate specific tracer’, but also over-expressed in neovasculature and therefore positive on various solid tumours, before briefly comparing its performance with Choline and GRPR (gastrin releasing peptide receptor) PET, noting the latter had the advantage of being more specific within the prostate.

She said choline PET/CT was not useful for the primary tumour but has a higher sensitivity and specificity for lymph node metastasis or distant metastasis than CT, MR or bone scan. It is useful, she added, to detect disease in biochemical recurrence, but only after a PSA of 2 ng/ml, and pointed out that salvage radiotherapy should be performed before PSA of 1.5 ng/ml. Therefore, whenever available, the PSMA-PET is now used for biochemical recurrence, given the significantly superior detection rate for PSA values as low as 0.2-0.5 ng/ml.

This led to a significant change in the radio oncologic approach for those patients, Burger explained, since early biochemical recurrence does not receive a ‘blind’ salvage radiotherapy to the prostate bed anymore, but can be targeted to the PSMA-positive lesion, often not localised in the prostate bed.

Burger added that, for staging high risk prostate cancer, PSMA-PET has a superior sensitivity compared to MRI or Choline PET for lymph nodes and distant metastasis.

Profiles:

Frederic Lecouvet works at the Catholic University of Louvain in Brussels, Belgium

Dr Irene Burger at the Nuclear Medicine Dept, University Hospital Zürich

28.12.2019