Article • Interdisciplinarity

All for one: a Belgian prostate unit at work

Pathologists, radiologists, urologists and radiotherapy specialists sit at the core of the treatment pathway for the patient, working together as a cohesive unit. In an innovative 2019 ECR session in Vienna, the prostate unit from Ghent University Hospital in Belgium outlined how the team works to deliver the best clinical outcome for patients.

Report: Mark Nicholls

Session chair Professor Geert M Villeirs of Ghent University Hospital – and President of the Belgian Society of Radiology – set the scene from the moment a patient is informed that Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) is elevated. ‘Our task,’ he said, ‘is to find the reason for it, either via non-invasive or invasive techniques. Once we know the pathologies, we have to treat – either surgically or non-surgically. All these building blocks come together as the prostate unit – the radiologist, pathologist, urologist and radiation oncologist – to discuss the patient.’

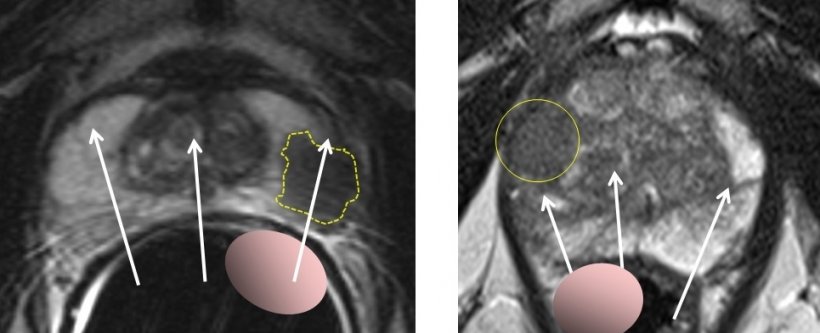

Right: Prostate cancer anteriorly in a large prostate, not palpable with digital examination and missed by the biopsy needles

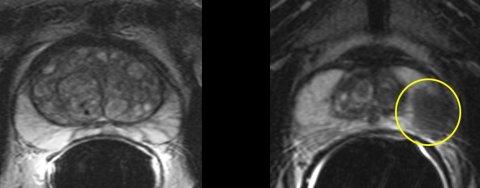

Transrectal ultrasound in cases of elevated PSA or abnormal rectal examination, he said, was a useful modality and ideal in biopsy to confirm the needle is in the right place in the prostate. However, he noted that prostate cancer is much more visible on MRI than ultrasound and that most prostate cancer (70%) is in the peripheral zone.

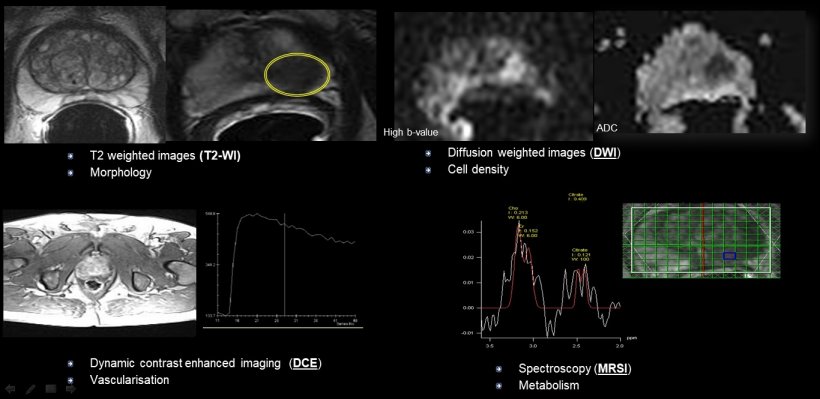

The Ghent team use multiparametric MRI (mp-MRI), combining elements of diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), Dynamic Contrast Enhanced imaging (DCE) and spectroscopy. ‘In terms of accuracy of prostate cancer detection, mp-MRI is accurate for larger tumours but frequently misses small or low-grade tumours,’ De Visschere explained. ‘However, this is not as important as it used to be as the diagnosis of prostate cancer and the treatment has changed.’

In addition to diagnosis, we can use MRI for local staging, detection of local recurrence and recurrence after radiation therapy

Geert M Villeirs

In the past, following PSA elevation and biopsy, all prostate cancers were treated but that led to overdiagnosis and over treatment. ‘Currently, the aggressiveness of the cancer is considered,’ he pointed out. ‘With a clinically significant prostate, cancer treatment can be surgery, radiation therapy and hormonal therapy. With a clinically insignificant prostate cancer there would be active surveillance and postponing treatment but with close follow up and treatment would only start in a case of evolution to clinically significant prostate cancer. ‘In addition to diagnosis, we can use MRI for local staging, detection of local recurrence and recurrence after radiation therapy.’

The team uses PI-RADS (Prostate Imaging – Reporting and Data System) as the reporting and communication tool. mp-MRI, he explained, is the ‘current-state-of-the-art imaging technique’ used to assess patients with suspected or confirmed prostate cancer, because it has excellent accuracy in detection or exclusion of high-grade prostate cancer.

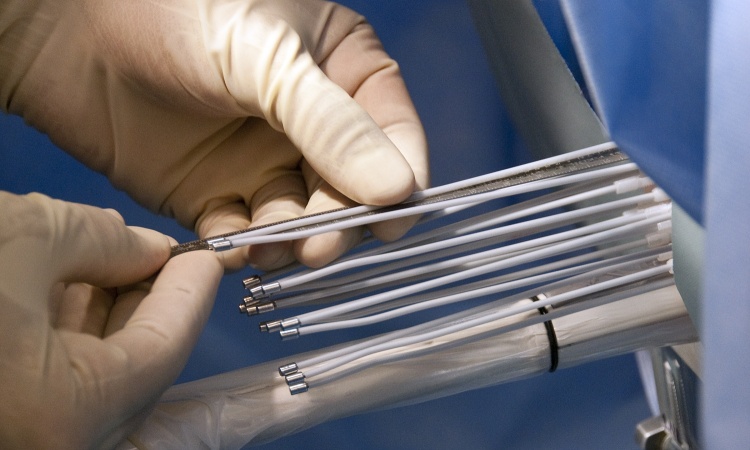

Pathologist Professor Sofie Verbeke from the hospital’s Department of Pathology offered an insight into tissue processing and sampling after receiving the core prostate biopsies. She outlined the importance of receiving several core biopsies and of every location in separate location-annotated containers in case the needle missed the area of cancer, or detected insignificant cancer but missed the more aggressive cancer area. Acinar adenocarcinoma is the most common subtype of prostate cancer and graded based on the Gleason score but, she emphasised, making a grading call is not always straightforward.

Urologist Professor Nicolaas Lumen detailed the range of surgical approaches and the decision-making process within that. He can use a finger to assess the T stage but believes MRI is better to differentiate between T2 and T3 tumours. With a radical prostatectomy there is the choice of open, laparoscopic or robotic surgery: laparoscopic is minimally-invasive but does not have 3-D vision and the instruments are rigid, whereas robotic surgery has 3-D vision and full movement instruments. ‘Operating time is decreased with robotic surgery, blood loss is significantly less and there’s a shorter stay for the patient in hospital,’ he explained. ‘Post-operative complications are reduced and pain is reduced with robotic surgery and we have reduced the complication rate to about 1% compared with 5% from open surgery.’ In terms of occurrence of impotence and urinary incontinence, there is no real difference between open and robotic surgery, he said.

MRI is also used to aid patient selection for radical prostatectomy and assess the stages of radical prostatectomy modifications - anterior versus posterior dissection, bladder neck sparing, nerve sparing and urethra sparing – as well as improving functional outcome without jeopardising cancer outcome. Dose, target delineation and patient positioning remain crucial aspects in delivering radiotherapy treatment to prostate patients.

Radiation oncologist Professor Valerie Fonteyne stressed the importance of having MRI within the treatment planning process to aid with positioning, adding that external beam radiotherapy is an excellent treatment option for patients with prostate cancer and there is now a tendency to move towards shorter radiotherapy regimens. ‘Close collaboration with the department of radiology is mandatory in order to improve the outcomes for our prostate cancer patients,’ Fonteyne added.

12.06.2019