The first MIRO … and the first steps towards guidelines

John Brosky reports

Clinicians gathering in Brussels for the first-ever conference on Molecular Imaging in Radiation Oncology (MIRO), from 18-20 March, will take the first steps toward setting practice guidelines for using PET scans to target radiotherapy, a task that will culminate with publication of these recommendations in September.

A popping of champagne corks is unlikely, yet this milestone is worthy of celebration because it validates evidence developed through 20 years of study and brings what has remained up to now a research technique out of the laboratory and into everyday clinical practice.

It is also a significant step in the careful process of advancing a technology that promises to shift the paradigm of medical practice profoundly from broad, population-based treatments toward patient-specific, personalised medicine.

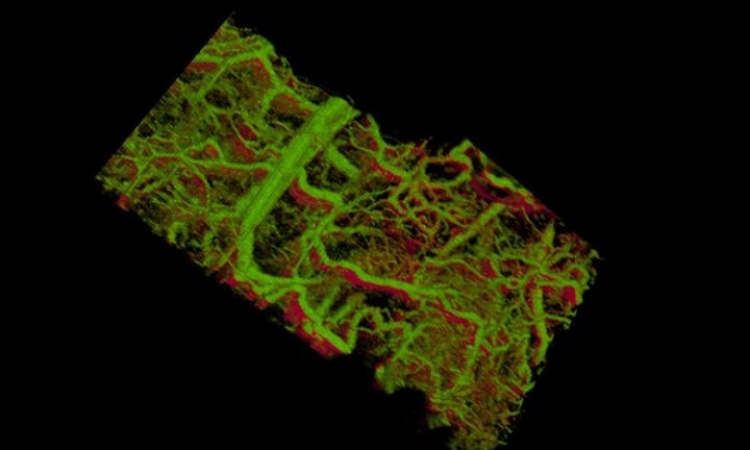

By using radiopharmaceuticals that attach to specific molecules, radiologists are now able to trace specific body functions, such as blood flow, oxygenation and metabolic interactions. These molecular images can then be superimposed on traditional anatomical images from computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), to render a vivid depiction of the specific disease state for each patient.

Molecular imaging holds a powerful potential as a tool for diagnosing disease across diverse fields of medicine, and the science is only in its infancy, according to Jean Bourhis MD, President of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO), which joined with the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) to organise the MIRO conference.

Yet, he said during our interview, molecular imaging has quickly become one of the main axes for innovative developments in oncology, where there is a great and unmet medical need to precisely target the dosage specific to each tumour. ‘There’s an urgent need to adapt the radiation as well as we can to the characteristics of a tumour, which was just not possible before functional molecular imaging because we were looking only at anatomical images,’ he explained. ‘Traditional radiology imaging can define the tumour target very well, so it is not a question of whether we can hit that target with the radiation. The question becomes: How can we affect the different characteristics within this mass?’

Functional image mapping of tumour characteristics is making an enormous difference for patient outcomes, he said. ‘Increasingly, with molecular imaging, we are defining the characteristics of the tumour, and at this moment we are investigating how we can drive the dose in areas of a tumour that are resistant. We know that hypoxia is a major factor for tumour resistance. With the ability to define specific hypoxic areas within the tumour, we can now adapt the radiation therapy to increase the dosage precisely on the hypoxic tissue and reduce it where there is not a need for this intensity.’

This ‘dose painting’, or applying different frequencies and different particles with the heterogeneous radiation of a tumour, will be the focus for presentations and discussions at the MIRO conference.

Beyond dose painting, the capability to identify tumour characteristics through molecular imaging will be practice changing for oncologists from the staging of cancers, to monitoring tumour response to treatment, through to follow-up care with patients.

‘I need to emphasise this is a work-in-progress, and we are not yet to a point of claiming a break-through. Yet adapting radiation for appropriate treatment is already making a tremendous change to oncological practice,’ he pointed out.’

MIRO is a first joint meeting to bring together nuclear medicine, functional imaging and radiation therapy to evaluate clinically the work done up to now and validate whether there is genuine benefit and improvement for patients, he explained. ‘We are at the very beginning of a step-by-step process,’ said Dr Bourhis, who believes the potential for personalising medicine will be realised over the next decade.

Molecular imaging is already moving rapidly out of exclusive research institutes to regional medical centres where the technology for PET scans are already in place. ‘The tools are there, and there are great developments coming in the pipeline. As we validate more markers that can be used for characterising tumours with PET, this will give a greater number of tests for equipment that is already installed,’ he explained.

The MIRO conference is the most recent initiative by ESTRO that each year sponsors 31 teaching courses, not only in Europe but throughout the world.

The society’s mission for greater education in radiation oncology for its 5,000 members is also supported by a biennial congress, set for September in Barcelona, where the guidelines for PET scan usage in radiation therapy are expected to be published.

ESTRO also regularly organises conferences dedicated to specialty practice areas, such as lung and prostate cancers.

In June, ESTRO will join forces with the American Society for Therapeutic Radiation Oncology (ASTRO), and the American Association of Medical Physicists (AAPM) for the first-ever trans-Atlantic meeting focused on Imaging for Treatment Assessment in Radiation Therapy (ITART).

In the emerging field of molecular imaging in oncology, this collaboration is essential, according to Professor Vincent Gregoire, the immediate past-President of ESTRO, who is actively working on the ITART conference. ‘There are many issues to be tackled, questions about equipment and ways to use them, questions about tracer development and validation in animal models, then in humans, and finally questions about how molecular imaging will allow physicians to better treat their patients.’

05.03.2010