Test identifies patients who benefit from targeted cancer drugs

USA - A new laboratory test - EGFRx, developed by the Weisenthal Cancer Group* - has accurately identified patients who would benefit from treatment with the molecularly-targeted anti-cancer therapies gefitinib (Iressa, AstraZeneca) and erlotinib (Tarceva, Genentech), according to clinical data published at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

the fact

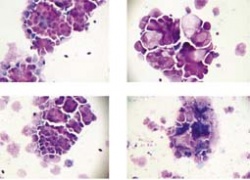

And the developer of the new assay, believes that the test, which he already provides routinely for a number of physicians in the USA, holds the key to solving some of the problems confronting a healthcare system seeking ways to best allocate available resources while accomplishing the critical task of matching individual patients with the treatments most likely to benefit them. ‘We feel that our approach may be used as a gold standard to more readily identify molecular profiling tests which are reflective of clinical drug effects,’ he added. ‘We test for drug effects using what we call whole cell profiling.’ The method involves removing live tumour cells from a cancer patient and exposing these, in the laboratory, to the new drugs. ‘A variety of metabolic and apoptotic measurements are then used to determine whether a specific drug was successful at killing that patient’s cancer cells. This cell profiling method differs from other tests in that it assesses the activity of a drug upon the combined effect of all cellular processes, using several metabolic and morphologic endpoints. Other tests, e.g. those that identify DNA or RNA sequences, or the expression of individual proteins, often examine only one component of a much larger, interactive process.’

Dr Weisenthal added that this might explain why EGFRx whole cell profiling is currently the only test to demonstrate a statistically significant association between prospectively reported test results and patient survival.

Using whole cell profiling, Dr Weisenthal’s group correlated test results - obtained by his lab and reported to physicians prior to patient treatment - with significantly longer or shorter overall patient survival, depending upon whether the drug was found to be effective or ineffective at killing the patient’s tumour cells in the lab. Patients prospectively identified by the team as favourable candidates averaged 485 days of life after treatment with the targeted therapy drugs. Conversely, patients identified unfavourably for the drugs averaged 75 days survival after receiving them. This compares with 76 days average survival among patients identified as unfavourable candidates and who did not receive a targeted therapy drug. Survival among patients identified by Dr Weisenthal as unfavourable candidates was therefore similar regardless of whether or not they received the targeted drugs.

Comparing the whole cell profiling approach with other types of tests Dr Weisenthal said: ‘Over the past few years, researchers have put enormous efforts into genetic profiling as a way of predicting patient response to targeted therapies. However, no gene-based test as been described that can discriminate differing levels of anti-tumour activity occurring among different targeted therapy drugs. Nor can an available gene-based test identify situations in which it is advantageous to combine a targeted drug with other types of cancer drugs. So far, only whole profiling has demonstrated this critical ability. The reason this is critical is because there is a growing array of targeted drugs to choose from. Also, most patients today are treated not with a targeted therapy drug alone but rather with a combination of chemotherapy drugs. Therefore, the existing DNA and RNA tests do not reflect the way cancer medicine actually is practiced today.’

Several new, targeted drugs have been introduced in the last few years and dozens more are on the horizon, he pointed out. ‘These ‘smart’ drugs focus their effects on specific, identifiable processes occurring within cancer cells. The new drugs are highly promising in that they sometimes provide benefit to patients who have failed traditional therapies. However, they do not work for everyone, they often have unwanted side effects, and they are all extremely expensive: some cost patients and insurance carriers $5,000 to $7,000 or more per month of treatment. Patients, physicians, insurance carriers, and the FDA are all calling for the discovery of predictive tests that allow for rational and cost-effective use of these drugs.’

* Weisenthal Cancer Group is a clinical cancer testing laboratory and research facility based in Huntington Beach, California. Details: www.weisenthal.org

01.07.2006