Breast cancer screening

Spanish experts clash over benefits and harms

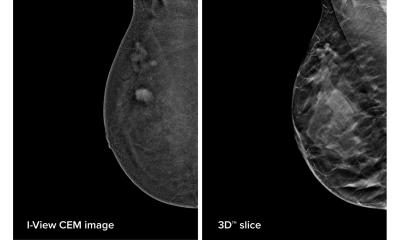

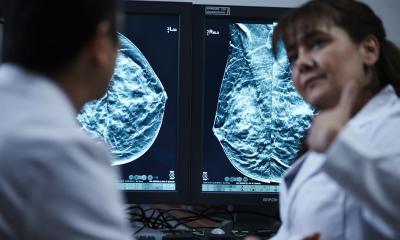

Breast cancer screening has helped to detect cancer in its early stages, but it is unclear how important this contribution is to mortality reduction because treatment has greatly improved. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment remain associated risks that need to be fully assessed for screening to be of real benefit. Leading experts in this field passionately discussed these controversies in a dedicated session during the 22-24 October Spanish Breast Congress in Madrid.

Report: Mélisande Rouger

Breast cancer affects 1.7 million new people annually, including 25,000 in Spain. Incidence is high, especially among younger generations, but mortality has decreased significantly since the 1990s, making Spain the country with the lowest breast cancer mortality rate in Europe.

Part of this success is due to the implementation of a national screening programme, which invites more than five million women annually, according to Dr Marina Pollán Santamaría, investigator at the national epidemiology centre of Carlos III Health Institute in Madrid. ‘Of course better treatment has helped curb cancer, but so has early diagnosis; being able to detect cancer in its early stages crucially improves outcome,’ she affirmed. A vision shared by many, including Dr Nieves Ascunce Elizaga from Navarra Public Health Institute. ‘The literature shows that screening decreases the risk of mortality by at least 25% in women aged between 50 and 69,’ she added.

The European Screening Network (EUROSCREEN), which compiles data collected by every running screening programme in Europe, estimates that screening reduces mortality by 25 to 30% in all invited women and by up to 48% in investigated women. (Summary of the evidence of breast cancer service screening outcomes in Europe and first estimate of the benefit and harm balance sheet. EUROSCREEN Working Group. J Med Screen 2012;19 Suppl1:5–13 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22972806).

The International Agency on Cancer Research (IACR) reviews all the available evidence on breast cancer (Breast-Cancer Screening — Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. Béatrice Lauby-Secretan, PhD, Chiara Scoccianti, PhD, Dana Loomis, PhD, Lamia Benbrahim-Tallaa, PhD, Véronique Bouvard, PhD, Franca Bianchini, PhD, and Kurt Straif, MPH, MD, PhD, for the International Agency for Research on Cancer Handbook Working Group. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:2353-2358;). It recently confirmed that screening helps to reduce mortality in the 70-74 group and overall for women between 50 and 69, a group in which benefits significantly outweigh potential adverse effects, according to Ascunce. However, research has not shown any benefit for women aged between 40 and 44 yet; some experts are in favour of screening women aged between 45 and 49, but evidence is limited. Therefore screening is generally not recommended in women below 50, except those who present with a significant risk.

This precaution is well grounded: screening does have adverse effects, first and foremost false positive results. The ensuing psychological and physical damage, which may occur when unnecessary invasive examinations and surgery are carried out, cannot be undermined. The appreciable incidence of over diagnosis has also prompted many to question screening’s role and benefits. ‘The worst price to pay with screening is probably to diagnose a tumour that could have receded on its own. However it’s impossible to know when this happens,’ Pollán pointed out.

Current estimates of over diagnosis in screening mammography vary between 0% to upwards of 30% of diagnosed cancer; contrast quality studies estimate over diagnosis to be around 6%. These estimates are important, because over-diagnosis may lead to overtreatment, i.e. to potentially exposing healthy or not so sick women to aggressive treatments like radiotherapy or mastectomy. So the question that really matters is whether screening is worth the price to pay?

No, according to José Schneider Fontan, a professor of obstetrics & gynaecology at Valladolid University, whose talk fuelled discussions among the panel. ‘Adverse effects clearly outweigh benefits. Three to four deaths are avoided for every 10,000 women subjected to screening over a ten-year period and 2.72 to 9.25 deaths are caused by overtreatment. The number of mastectomies also significantly increases with screening,’ he said.

Schneider based his presentation on the work of one of the most recognised opinion leaders on breast cancer worldwide, Michael Baum, professor emeritus of surgery and visiting professor of medical humanities at University College London. Over time, Baum, a pioneer of breast cancer screening in the UK, has over time become critical of the breast cancer screening programme, arguing that women are not receiving accurate and complete information on the actual benefits and risks of the procedure. (Michael Baum: Harms from breast cancer screening outweigh benefits if death caused by treatment is included. BMJ 2013;346:f385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f385).

Part of the problem with overtreatment stems from the status of carcinoma in situ, which is classified as cancer although it is a pre cancerous lesion, according to Schneider. ‘It is much easier to perform mastectomy in carcinoma in situ than it is in actual carcinoma, hence the large number of interventions carried out in these patients,’ he explained.

The gynaecologist also questioned the efficacy of breast cancer screening by comparing results obtained with cervix cancer screening; introduced in the 1950s, the latter translated in a drastic reduction of mortality whereas the drop has been more moderate for breast cancer screening. Causes for mortality reduction are therefore to be found elsewhere. ‘The introduction of Tamoxifen and hormonal treatment in the 80s has driven down mortality, not screening. Proof for that is that mortality of prostate cancer, which is being treated in the same way as breast cancer, has decreased in equal numbers,’ Schneider pointed out.

In particular, a study published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) raised doubts about breast cancer screening (Breast cancer mortality in neighbouring European countries with different levels of screening but similar access to treatment: trend analysis of WHO mortality database, BMJ 2011;343:d4411, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4411). Mortality was compared in countries of similar size, population and economic means, which practised either systematic or opportunistic screening. The authors found that mortality reduction was the same in all countries observed. ‘This clearly demonstrates that mortality reduction is due to treatment, not screening. If screening worked, we would have noticed over time,’ he said.

Ascunce strongly criticised this position, discarding the BMJ study on the grounds of its observational nature. She also opposed the figures mentioned by Schneider and backed up her stand with EUROSCREEN data. ‘Nine deaths are avoided per 1,000 women subjected to screening over a 20-year period, during which four cases of cancer will be over diagnosed,’ she said.

Optimising screening by selecting women who present with more risks and focus efforts on these patients may be a solution, according to Pollán, who offered a more nuanced view. Pollán participated in a prospective study together with the Navarra Public Health Institute breast screening programme, in which she used and recalibrated the Gail model developed in the USA. ‘We found that four percent of the women observed were above the five-year risk threshold,’ she said.

PROFILES:

Nieves Ascunce Elizaga MD specialises in preventive medicine and public health, and leads the breast cancer early screening programme in Navarra. This began in 1990, after she helped to design and implement the programme, a part of the European Breast Cancer Screening Network, and several working groups on screening evaluation. A member of national and international expert committees, she has taken part in many conferences and talks, authored several screening and breast cancer publications, and is involved in several screening research projects.

José Schneider Fontan MD, professor of obstetrics & gynaecology at Valladolid University, Spain, previously held the same role at King Juan Carlos University, Madrid. He is also Research Director at the Rio Hortega University Hospital in Valladolid. After gaining his medical degree at Freiburg University in Germany in 1980 he received Spanish board certification in obstetrics & gynaecology in 1984. A PhD followed from Cantabria University in Santander in 1986 and, in 1989, German board certification in obstetrics & gynaecology from the Baden-Württemberg Federal State. His 110+ publications, on every aspect of gynaecology practice, also focus on breast cancer diagnosis and treatment.

06.01.2016