Richard III – modern imaging transforms a historical image

Mark Nicholls discovers how a CT scan at a British hospital played a critical role in identifying the long-lost remains of a 15th Century English king

For many centuries, the image of the English monarch King Richard III was that created by playwright William Shakespeare, who depicted the last Plantagenet King of England as an evil, hunch-backed murderer. That image endured virtually unchallenged over the centuries – primarily because of a lack of any contemporary paintings of the monarch, or the recovery of his remains.

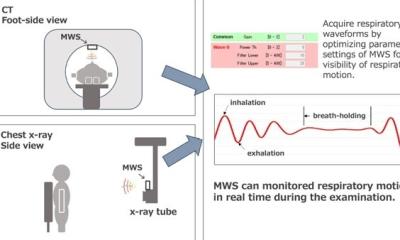

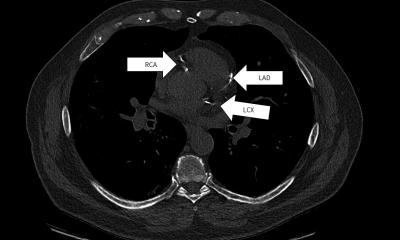

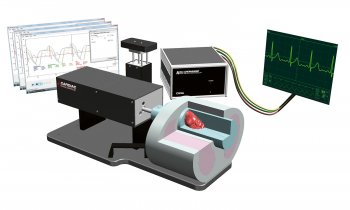

The remarkable discovery of a skeleton a few months ago on the lost site of a forgotten church beneath a car park in Leicestershire, in the heart of England, was to change all that. In February, DNA analysis confirmed the bones to be those of King Richard III, who is known to have been killed at the Battle of Bosworth on 22 August 1485. It was modern hospital imaging technology that was to throw an added dimension on the remains and also help experts recreate his facial features. A team from the radiology department at Leicester Royal Infirmary scanned the bones using post mortem CT scanning protocols, similar to a normal clinical scan, to produce detailed images of the bones. The unit has had a research interest and expertise in post mortem CT scanning for several years, so was well placed to offer the skills needed by archaeologists to unravel the mysteries surrounding Richard III’s remains. Claire Robinson, lead forensic radiographer at University Hospital Leicester carried out the scan with Professor of Radiology Bruno Morgan and Home Office pathologist Professor Guy Rutty and his team from the East Midlands Forensic Pathology Unit. The bones were initially laid out on the scanner as close as possible to the anatomical position in which they were found.

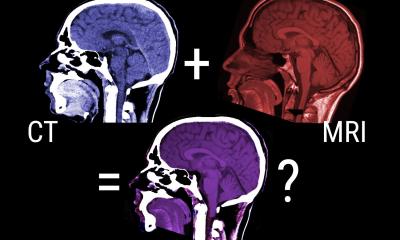

After the initial analysis of the images, a further scan of the bones was taken, using a bespoke polystyrene template to better position them, in order to reconstruct the images to make a ‘virtual’ three-dimensional model. Professor Morgan said that as well as conducting a standard clinical scan using hi-res bone protocols, the University of Leicester team also used micro-CT to conduct a long but very high resolution scan of the skull. This was used to create the 3-D print used by the team at Dundee University to help reconstruct the facial features of the dead king (see above). After his death, Tudor historians, as well as Shakespeare, portrayed Richard III as a villainous monarch with a curved spine who was rumoured to have murdered his brother’s young sons in the Tower of London. He was eventually challenged by Henry Tudor (later Henry VII) and killed at Bosworth after only two years on the throne and given a hurried burial beneath the church of Greyfriars in the centre of Leicester city, in a clumsily cut grave with sloping sides and too short for the body, forcing the head forward. Greyfriars church was demolished in the 16th Century and its exact location was forgotten.

However, a team of enthusiasts and historians managed to trace the likely area – and, crucially, after painstaking genealogical research, they found a 17th generation descendant of Richard’s sister with whose DNA they could compare any remains. Joy Ibsen, from Canada, died several years ago but her son, Michael, who now works as a furniture maker in London, provided a sample. The Leicester scans show that the skeleton’s spine was indeed curved, a condition known as scoliosis, but there was no trace of a withered arm or other abnormalities described in the more extreme historical characterisations of the king. Professor Morgan said: ‘Richard III’s bones were scanned three times and while it was relatively straightforward when compared to difficult clinical cases, there was the constant care needed because of the age, delicacy and importance of the remains. ‘For us, one of the key elements was in trying to work out just how crooked he was. There is no doubt that the skeleton had scoliosis, but it was a case of working out just how bad it would have been and how easily it would have been to hide it. ‘It has been a great opportunity to be involved in the project and learn a little more about Richard III’s scoliosis and about the man himself. He did have scoliosis, though it was not as exaggerated as Shakespeare made out, but it was not made up.

‘The big advantage of the scanning is it means that once the bones go back into the earth again, we have still got a very accurate facsimile of his bones, we have a permanent record for people to use for research in the future, especially as the CT images are being used to make a full 3-D print of the skeleton at the University of Loughborough.’ With University of Leicester osteo-archaeologist Jo Appleby and Piers Mitchell, anthropologist at the University of Cambridge and consultant paediatric orthopaedic surgeon for Peterborough and Stamford Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, who have studied the skeleton’s scoliosis, Professor Morgan will help produce a scientific paper looking particularly at how bad the scoliosis of Richard III would have been. He said that the Richard III project has been invaluable in promoting the role of the post mortem imaging team at Leicester and its capabilities. Post-mortem CT (PMCT) is becoming an option as a minimally invasive alternative to post-mortem examination. Leicester has become an established centre in PMCT, developing post mortem coronary imaging techniques and running a number of courses designed to introduce professionals to the use of computed tomography (CT) in the investigation of sudden death. The bones are of a man in his late 20s or early 30s and have been carbon dated to 1455-1540. Richard was 32 years old when he died in battle. The skeleton had suffered 10 injuries, including eight to the skull, at around the time of death.

Dr Appleby said: ‘The CT scans of the bones, carried out at Leicester Royal Infirmary by the Radiology Imaging Unit have been a crucial part of the investigations. The threedimensional images of the skeleton that have been produced have played a central role in our interpretation of the injuries. In addition, the CT scans mean that we will have a full record of the skeleton even after the bones are reburied.’ While the CT scan provided a permanent 3-D record of the bones which cannot be obtained by other means, enabling images and models to be reproduced, minimising any potential damage that could be caused by repeated handling of the fragile bones and facilitating further analysis and comparisons after the bones are interred, the Leicester CT scans were also critical in helping build up an image of the muchmaligned monarch’s facial features. When it came to reconstructing Richard III’s face, the Dundee team used CT scans and photographs of the skull, which they ran through a computer programme.

Caroline Wilkinson, Dundee University’s professor of craniofacial identification, said clues from the skull were used to reconstruct features while a specific formula enabled researchers to predict what the soft nose would look like from the underlying bone and the shape of the brow. ‘The width of the mouth can be determined exactly by the position of the teeth,’ Professor Wilkinson explained. ‘The little bump on the outer orbit is where the outer corner of the eye is. We can use these anatomical standards to help us rebuild the face.’ Over the centuries, some scholars sought to re-evaluate Richard III’s brief reign and highlight his good work, such as reforming the English legal system. That debate is set to continue. But with the bones scanned and confirmed as the remains of King Richard III, planning is now under way for a formal reburial of a long-lost English monarch.

07.03.2013