© MPI CBS; Image source: Brammerloh et al., Radiology 2022 (CC BY 4.0)

News • Potential of nigrosome imaging

Parkinson's: Misconception of 'swallow-tail'-sign rectified

A team of neurophysicists, led by Malte Brammerloh of the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Leipzig (MPI CBS), found evidence that the identification of a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sign for Parkinson's diagnosis, as a specific anatomical region in the brain, is widespread but not at all correct.

A better understanding of the MRI contrast of the anatomical region called "nigrosome 1" has led to clarification of the misunderstanding and could even help diagnose Parkinson's earlier.

"That MRI sign, called the swallow-tail sign, includes part of the 'nigrosome 1' anatomical region, but it looks very different," explains the lead author of the study, now published in the journal Radiology. "This is relevant to the clinical field because the notion that the 'swallow-tail sign corresponds to nigrosome 1' is deeply engrained but should be revised.", says Malte Brammerloh.

In Parkinson's disease, dopamine-producing nerve cells from the substantia nigra in the midbrain die. This causes movement disorders such as slowing, stiff muscles, and tremors in the patients. The nerve cells in nigrosome 1, which is within the substantia nigra, are affected particularly severely and early. With high-resolution MRI imaging it is possible to image the swallow-tail sign, which is located in the posterior third of the substantia nigra and, according to current textbook knowledge, corresponds to nigrosome 1.

We believe that with this new knowledge, it will be easier to understand how anatomy and MRI contrasts are related and how new MRI markers can be developed for the early diagnosis of Parkinson's

Malte Brammerloh

In healthy people, the MRI image shows a signal-rich elongated structure surrounded by signal-poor areas at the front and sides. This special shape is reminiscent of a swallow tail, which is where the name came from. According to the common interpretation of the sign, the death of neurons in nigrosome 1 in Parkinson's patients leads to the swallow-tail sign eventually no longer being recognisable. If this is the case, there is a high probability of Parkinson's disease.

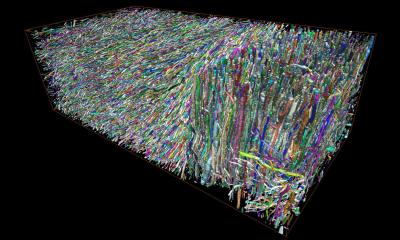

Malte Brammerloh and his colleagues have now combined microscopic 3D examinations of human brains after death with MRI technology to show that nigrosome 1 and the radiological swallow-tail sign only partially overlap and are in fact very different. The scientists therefore argue that the swallow-tail sign should not be equated with the nigrosome 1 region. This allows a reinterpretation of the diagnostic swallow-tail sign and at the same time opens up new avenues for specific nigrosome imaging. Brammerloh adds, "We believe that with this new knowledge, it will be easier to understand how anatomy and MRI contrasts are related and how new MRI markers can be developed for the early diagnosis of Parkinson's."

Source: Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences

21.08.2022