Oncology

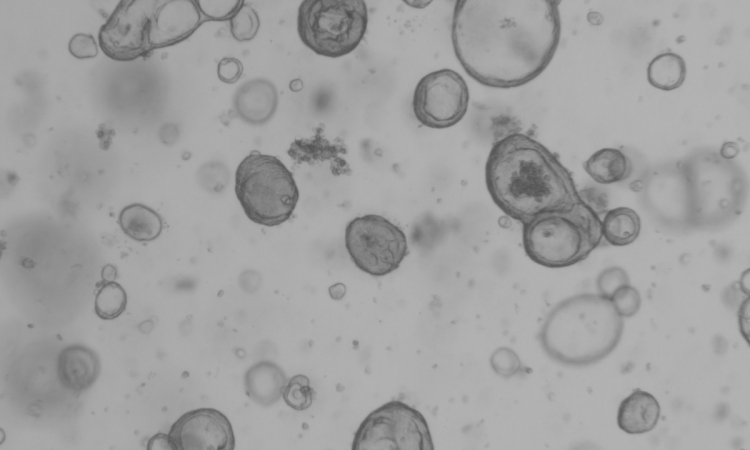

One cancer – many tumors

In studies on prostate cancer, scientists from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) simultaneously investigated the genetic and epigenetic development of the tumors.

They used a parallel approach to analyze both the genome and the methylation of the DNA in various tissue samples from a tumor and its metastases. Both processes equally reflect the complex composition of multiple different daughter clones in advanced tumors. As DNA methylation impacts the activity of genes, detecting diverging methylation patterns may help understand the origins of metastases and choose more specific treatment strategies.

Advanced tumors are characterized by a multiplicity of defects in their genome. In many cancers, thousands of small “typos” in the genetic material lead to transformed, dysfunctional proteins. Prostate cancer, however, typically exhibits larger genomic defects where whole segments of DNA are lost, duplicated or arranged in the wrong order. In addition to these structural defects, tumors of the prostate are also characterized by huge differences in the patterns of DNA methylation. The cell uses these small chemical tags, which are a type of epigenetic mechanism, to regulate various processes including the activity of particular genes.

As cancer progresses, structural alterations in the genome accumulate and lead to an “evolution” of the cancer cells. As a result, an advanced tumor is composed of a group of various “daughter clones”. This means not only that each tumor of the prostate is unique but also that each individual tumor is composed of different clones that may differ in clinical aspects such as resistance to treatment.

Scientists in the group of Christoph Plass at the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) and collaborators in the German ICGC Consortium “Early onset prostate cancer” have now studied whether the epigenetic changes in a tumor can also be used to trace its evolution and hence the composition of its various daughter clones. In five cases of prostate cancer they simultaneously analyzed the genes and their methylation.

The researchers compared tissue samples taken from different parts of a tumor with surrounding tissue that was not yet completely transformed as well as with metastases in the lymph nodes. They showed that both the structural genomic alterations and the changes in the methylation patterns equally reflected the evolution of the individual tumors. It seems that the evolution of the epigenome progresses in a process parallel to the appearance of new structural genomic changes.

An important observation is that metastases not necessarily form at the “end” of a tumor’s development. In one case, for example, the metastases lacked the chromosome abnormalities that characterized all other tissue samples from this tumor, suggesting that the daughter tumors had developed early on. In some of the cases under investigation, the metastases arose from a common progenitor, while in others they originated from different daughter clones. It generally holds true that metastases always exhibit characteristics that are not found in the other daughter clones. As a rule, these epigenetic or genetic changes affect genes that lend metastasizing cancer cells their typical properties.

28.08.2014