‘Mini-Brains’: Evidence of Zika’s toll on fetal cortex

Studying a new type of pinhead-size, lab-grown brain made with technology first suggested by three high school students, Johns Hopkins researchers have confirmed a key way in which Zika virus causes microcephaly and other damage in fetal brains: by infecting specialized stem cells that build its outer layer, the cortex.

The lab-grown mini-brains, which researchers say are truer to life and more cost-effective than similar research models, came about thanks to the son of two Johns Hopkins scientists and two other high school students who were doing summer research internships. They had the idea to make the equipment for growing the mini-brains with a 3-D printer. These so-called bioreactors, and the mini-brains they foster, should open other new and valuable windows into human brain development, brain disorders and drug testing — and perhaps even produce neurons for treatment of Parkinson’s disease and other disorders, the investigators say.

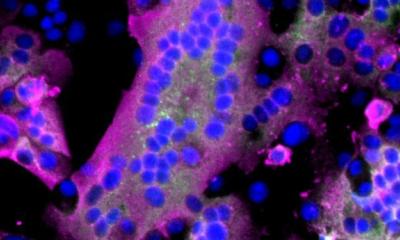

“We have been working for three years to develop a better research model of brain development, and it’s fortunate we can now use this one to shed light on the major public health crisis posed by Zika infections,” says Hongjun Song, Ph.D., professor of neurology and neuroscience at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine’s Institute for Cell Engineering. “This more realistic, 3-D model confirms what we suspected based on what we saw in a two-dimensional cell culture: that Zika causes microcephaly — abnormally small brains and heads — mainly by attacking the neural progenitor cells that build the brain and turning them into virus factories.”

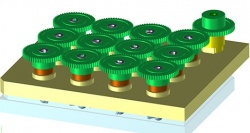

In recent years, researchers in various fields have begun to grow tiny organs from human stem cells to get a better view of development and disease, and speed the search for new drugs. But existing techniques for creating and working with mini-brains were limiting because of the organ’s complexity, Song says. Though the mini-brains themselves are about the size of a pinhead, the bioreactors where they grew were comparatively large, about the size of a soda can. That made working with the mini-brains expensive, given the high cost of the nutrients needed to cultivate human stem cells in the lab, he says, as well as the expense of chemical growth factors that guide the tissue to organize itself like a real brain. Few labs could afford to grow enough mini-brains to be useful for research, Song says, and those that did produced tissues with cells specialized for different parts of the brain mixed together at random.

Song and his wife and research partner, Guo-li Ming, M.D., Ph.D., professor of neurology, neuroscience, and psychiatry and behavioral sciences, found a way to improve the bioreactors from an unexpected source: their son and two other high school students, from New York and Texas, who spent a summer working in the lab. The students had worked with 3-D printers and thought they could be the key to producing a better bioreactor, one that would fit over commonly used 12-well laboratory plates and spin the liquid and cells inside at just the right speed to allow the cells to form brains.

Of course, it wasn’t that simple, Song says. Graduate student Xuyu Qian and postdoctoral fellow Ha Nam Nguyen, Ph.D., spent years determining factors such as what that optimum speed was, as well as which chemicals and growth factors should be added at what times to yield the desired result.

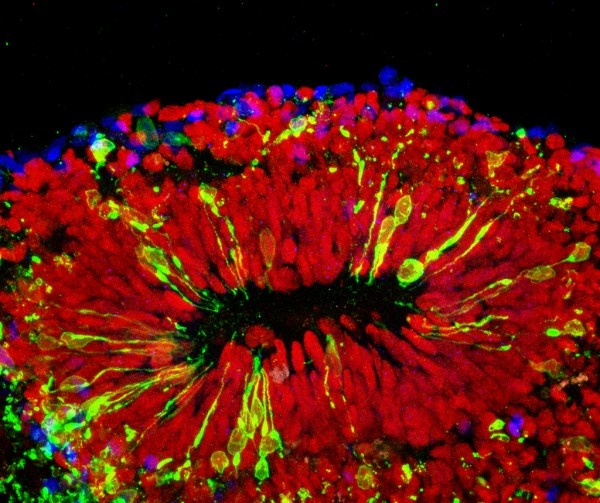

The group has so far used the new bioreactor, dubbed SpinΩ, to make three types of mini-brains mimicking the front, middle and back of a human brain. They used the forebrain, the first mini-brain with the six layers of brain cell types found in the human cortex, for the current study on Zika.

“One thing the mini-brains allowed us to do was to model the effects of Zika virus exposure during different stages of pregnancy,” says Ming. “If infection occurred very early in development, the virus mostly infected the mini-brains’ neural progenitor cells, and the effects were very severe. After a while, the mini-brains would stop growing and disintegrate. At a later stage, mimicking the second trimester, Zika still preferentially infected neural progenitor cells, but it also affected some neurons. Growth was slower, and the cortex was thinner than in noninfected brains.”

Source: Johns Hopkins Medicine

26.04.2016