News • Unintended use of wearables

People with long Covid may "hack" their fitness trackers – for better or worse

At the beginning of the pandemic, when people suffering from the long-term effects of Covid-19 faced more questions than answers from doctors, they began collecting data on themselves using fitness watches to better understand their disease.

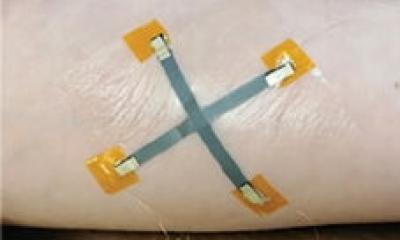

Image source: Kristian Bjørn-Hansen, University of Copenhagen

Sarah Homewood was one of them and has since researched the phenomenon. According to her research, while self-monitoring can offer people more certainty and control over the disease and their bodies, it can also lead to anxiety.

"Time to get up", "You've walked less than average", "You can still reach your activity goal"... An ever-growing number of people are being paced forward over the past few years by small wearable technology – typically worn around the wrist like a watch, with built-in sensors to monitor their physical activities and health. Whether as sports watches, fitness trackers or software enabled smartwatches, these devices are now being used to manage disease as well, serving beyond their intended purpose as fitness-tracking technology.

Long Covid is an example of a disease where sufferers have used fitness tracking watches, contradictory to their intention and design, to limit strenuous activities and conserve energy. E.g. by making sure their heartrate didn’t go to high on walks or deciding whether or not to shop for groceries based on the steps already tracked.

Sarah Homewood, an assistant professor at the Department of Computer Science, has experimented with this on both her own body and through research. She is behind two studies, both of which examine the use of fitness technology for long Covid-related self-monitoring. In her most recent article, published in DIS '24: Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, she examines the use of fitness trackers among twenty-one individuals with long Covid and concludes that self-monitoring has both good and bad aspects for users: "Across all participants, the most common traits were a sense of greater control and certainty about the disease, better opportunities to document symptoms to oneself, family and their doctors, but also situations of uneasiness or anxiety triggered by use," she says.

There is a clear tendency for data to eclipse experience. The data users get can have a major impact on how they assess situations. In some contexts, it can be a source of unrest, while in others, certainty and security

Sarah Homewood

The researcher highlights one participant's visit to a float tank as an example. The visits had been a peak of relaxation for the woman, until data from her fitness tracker reported elevated stress levels, after which the woman stopped going to the activity. "There is a clear tendency for data to eclipse experience. The data users get can have a major impact on how they assess situations. In some contexts, it can be a source of unrest, while in others, certainty and security," says the researcher.

The results also support her first research study on the subject – a so-called autoethnographic study of her own illness and use of self-monitoring, which was published in CHI '23: Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. The researcher’s experiences as a long Covid sufferer using of a Fitbit watch didn’t just evolve into her research study, they served as her personal path to recovery. "I quickly realized that I needed to use the watch contrary to its intentions. I had to counter its design. Whenever the watch informed me that I had walked far and needed to keep going to reach a new distance goal, it was my cue to sit down. Because the watch provided me with 'hard evidence' to compare my experiences with, I could actually begin to piece together what worked and what exacerbated problems for me," says the researcher.

Sarah Homewood was able to adjust her physical activities based on the watch's heart rate readings, and in doing so, avoid paying a hefty price for overexerting herself. Ever since, she has seen this "hack" of the watch's functionality to control her own physical activities mirrored in the new study’s participants.

Recommended article

Article • Covid-19

Coronavirus update

Years after the first outbreak and spread of coronavirus Sars-CoV-2, its impact can still be felt in everyday life. Keep up-to-date with the latest research news, political developments, and background information on Covid-19.

The new study shows that both the positive and negative aspects experienced by the researcher are recurrent trends. Participants find that wearable fitness technology gives them more certainty that their experiences are real, and that they gain a degree of control over the disease and their body by using the data to understand and regulate their energy expenditure, among other things. The reality for the participants where an unknown disease without a name. The measurements therefore become a way to understand a new disease that, despite resistance, can then be presented to a doctor for documentation.

The study shows that some of the participants’ doctors flatly rejected watch data. Other participants were met more positively, and some were even able to use it directly and get a diagnosis from the doctor. "This is something relatively new and healthcare professionals need to get used to the fact that this type of data exists when they meet patients. But since fitness watches aren’t approved or designed to be medical devices, the information should also be taken with a grain of salt. Nevertheless, I don't think it's appropriate for doctors to be totally dismissive," says the researcher, and continues: Where a number of doctors may be skeptical about the idea of self-monitoring because they fear that it can lead to anxiety in laypeople and unnecessary doctor visits, Homewood points out that the opposite is also often the case: many participants express a feeling of empowerment in being able to do something to help themselves.

This technology will improve. It is here to stay. We need doctors who embrace the technology and relate to the opportunities and risks that exist, and in doing so, help it to develop

Sarah Homewood

She also emphasizes that technology can really help. "Take my example: despite nearly fainting, measurements taken at the doctor showed nothing. Data from the watch revealed that it was due to my heart. For this, I am grateful. But of course, we need to help this technology along and develop it with respect for its possibilities and as well as the risks that exist in the form of unnecessary anxiety, erroneous self-diagnosis, etc.," says the researcher.

Pointing out that even though data from these watches are yet imprecise, the watches are able to collect data from longer periods, which gives the ability to see trends, rather than just the one data point measured in the doctor’s office. “Also this technology will improve. It is here to stay. We need doctors who embrace the technology and relate to the opportunities and risks that exist, and in doing so, help it to develop," she says.

The researcher is currently in contact with several companies that are working on software improvements tailored for diseases. "It isn’t ideal for people who are ill to be measured by apps intended for sports and fitness. Being compared to a healthy body and asked to do more, when one’s own body doesn’t want to, can be an unpleasant experience. It gives feedback to people who are ill that isn’t appropriate and can trigger anxiety," she says.

The researcher is also trying to speed up the development of a dashboard interface for presenting data that bridges the gap between self-monitoring patients and their medical providers. "There is a need to improve communication between those who use these tools and their doctors about their data. That's why we're working to develop a dashboard that can be used differently by users and healthcare professionals. In doing so, users will gain a better overview, while doctors can access details that require a trained eye to interpret," says Sarah Homewood.

Source: University of Copenhagen

28.09.2024