News • Henipaviruses

Lethal viruses hijack cellular defences against cancer

Monash University’s Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI) researchers have identified a new mechanism used by Henipaviruses in infection, and potential new targets for antivirals to treat them. Their findings may also apply to other dangerous viruses.

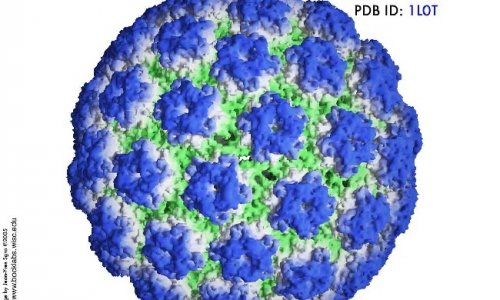

Henipaviruses are among the deadliest viruses known to man and have no effective treatments. The viruses include Hendra, lethal to humans and horses, and the Nipah virus, a serious threat in East and Southeast Asia. They are on the World Health Organization Blueprint list of priority diseases needing urgent research and development action.

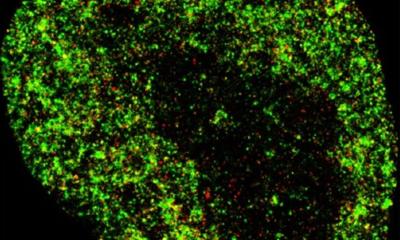

A collaboration of scientists, led by Monash BDI’s Dr Gregory Moseley, found that Henipaviruses hijack a mechanism used by cells to counter DNA damage and prevent harmful mutations, important in diseases such as cancer. Dr Moseley said it was already known that the viruses send a particular protein into a key part of a cell’s nucleus called the nucleolus, but it wasn’t known why it did this.

The researchers showed that this protein interacted with a cell protein that is an important part of the DNA-damage response machinery, called ‘Treacle’. This inhibited Treacle function, which appears to enhance henipavirus production. “What the virus seems to be doing is imitating part of the DNA damage response,” Dr Moseley said. “It is using a mechanism your cells have to protect you against things like ageing and mutations that lead to cancer. This appears to make the cell a better place for the virus to prosper,” he said. According to Dr Moseley, it is possible that blocking the virus from doing this may lead to the development of new anti-viral therapies.

“What the virus seems to be doing is imitating part of the DNA damage response.”

Dr Gregory Moseley

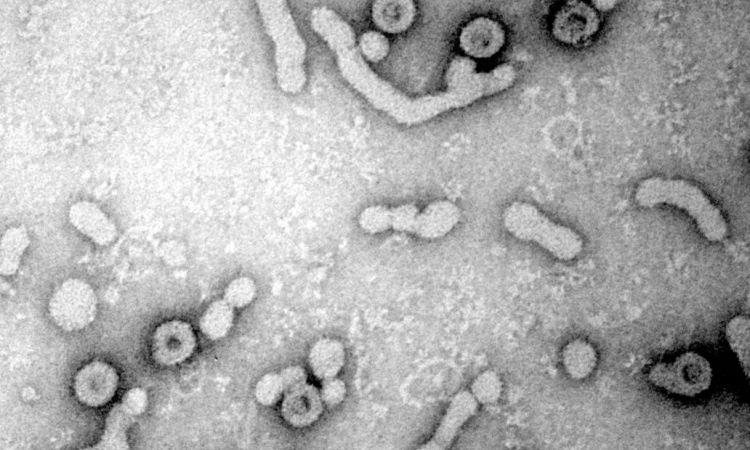

Both Hendra and Nipah, which spread from bats to other animals and humans, emerged in the 1990s; Hendra in an outbreak in Brisbane in 1994 and Nipah in Malaysia in 1998. The viruses, which share outcomes including inflammation of the brain and severe respiratory symptoms, have since caused multiple outbreaks of disease. Nipah has killed several hundred people, including at least 17 people in the Indian state of Kerala in June.

“Nipah is not so important in Australia but it’s the one people are concerned about internationally,” Dr Moseley said. “Like Ebola, if you get a really big outbreak and it’s not containable, it could be disastrous.” He said that study’s findings add insights into how viruses behave more generally. “We identified a new way that viruses change the cell, by using the very same machinery that the cell normally uses to protect itself from diseases like cancer.”

Source: Monash University

08.08.2018