© Karin Kaiser / MHH

News • Personalised aftercare

Immunosuppression after transplant: as much as necessary, as little as possible

After a liver transplant, patients have to take immune-suppressing drugs for the rest of their lives. These so-called immunosuppressants prevent the organ from being rejected.

However, the drugs increase the risk of cancer and serious infections. They can also significantly impair kidney function and even lead to dialysis. In order to be able to give those affected as much immunosuppression as necessary, but as little as possible, doctors at Hannover Medical School (MHH) rely on a special aftercare programme: using tissue samples, they control the immunosuppression for each affected person individually.

Details on the concept have been published in the American Journal of Transplantation.

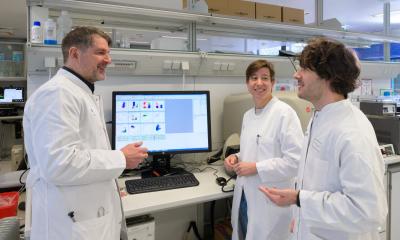

"More transplant patients still die from diseases promoted by taking the immunosuppressants than from transplant failure," explains private lecturer Dr Richard Taubert, senior physician at the liver transplant outpatient clinic of the MHH Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endocrinology. "In our programme, biopsy has directly impacted our follow-up in about 80 per cent of patients, and immunosuppression has been reduced in up to 60 per cent of patients." Emily Saunders, assistant physician and PhD student in the MHH Clinic for Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endocrinology adds, "The comparison to a previous cohort of patients before the introduction of the new follow-up programme showed that the lower immunosuppression did not increase the risk of rejection, but had a positive effect on the patients' kidney function." The doctors were also able to identify damage to the transplant earlier and treat it, for example, by using a different or higher immunosuppression.

As part of her doctoral thesis, Emily Saunders performed protocol biopsies in liver transplant patients with normal liver values from one year after transplantation. During a biopsy, doctors remove a small piece of tissue from the patient's liver through the abdominal wall using a fine needle. This procedure only takes about a second. The site is locally anaesthetised beforehand.

Controlling immunosuppression after liver transplantation without biopsies is flying blind

Elmar Jäckel

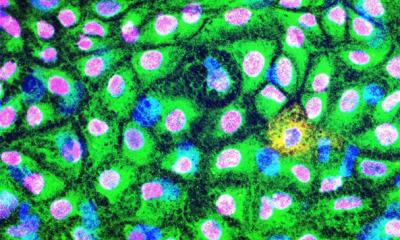

A total of 211 patients could be examined. Only about one third of the protocol biopsies were unremarkable. More than 60 per cent of the samples showed damage to the transplant liver, such as scarring of the tissue or inflammation. "We would not have been able to detect these damages on the basis of the laboratory values and the clinical condition of the patients, so that controlling immunosuppression after liver transplantation without biopsies is flying blind," says Dr. Elmar Jäckel, also a senior physician in the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endocrinology, who coordinates the programme together with Dr. Taubert.

"The observations prove that the protocol biopsies are safe and do not result in any relevant complications for the patients," says Dr Taubert. Based on the result of the biopsy, the liver values, the kidney function and other concomitant diseases, the medical team was able to adjust the immunosuppression individually for each patient. Because: Not every patient needs the same strength of immunosuppression, a few patients could even manage without any at all. In the following months, the patients were closely monitored by their general practitioners. One year after the change in immunosuppression, the patients came back to the outpatient clinic for a check-up.

Only a few transplant centres perform protocol biopsies, firstly because of the perceived risks such as bleeding and secondly because until a few years ago it was unclear how to evaluate the above-mentioned changes in the liver biopsy. "Long-term survival beyond the first year after liver transplantation has hardly improved in the past 30 to 40 years, despite considerable improvements in surgery and drug therapy. Too many organs are still lost. With regular protocol biopsies, this will hopefully change," says Professor Dr Hans Heiner Wedemeyer, Director of the MHH Clinic for Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endocrinology. This is desirable for the patients, he adds.

Source: Hannover Medical School

03.10.2021