Article • Blood test & AI power

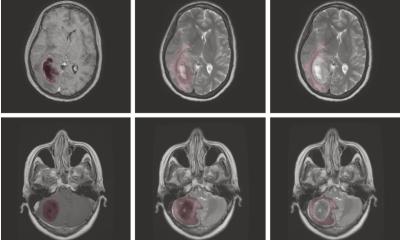

Early brain tumour detection – within minutes

A simple blood test coupled with artificial intelligence (AI) analysis could help spot the signs of a brain tumour sooner in patients.

Report: Mark Nicholls

Brain tumour diagnosis is difficult: patients often see their family doctor (GP) several times before referral for a scan. However, research presented at the 2019 National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) Cancer Conference in Glasgow last November suggests the blood test – combined with machine learning – could detect a brain tumour within minutes. The University of Edinburgh and University of Strathclyde researchers hope the non-invasive test will simplify and speed up diagnosis; provide an efficient, accurate and cost-effective option to identify brain tumours, and deliver better stratification of those needing urgent brain scans.

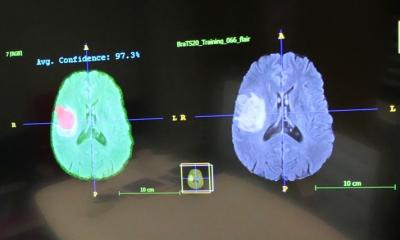

Lead researcher Dr Paul Brennan explained that, following the blood test, which generates complete data sets for patients, Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier-transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy is used to identify the cancerous biosignature in serum and differentiate between glioblastoma and primary cerebral lymphoma. An AI pattern recognition algorithm then shows which samples indicate brain tumour.

‘Spectroscopy gives a snapshot of thousands of molecules at once,’ he explained, ‘but we wouldn’t be able to analyse that data without a machine learning approach. While not knowing which the important molecules are that predict the difference in behaviour, we do know that we can reproducibly identify them in the tumour population and identify their absence in the non-tumour population. So, the real innovation is to be able to handle large amounts of data and not have to pre-suppose a biological mechanism. That’s where the opportunity is.’

Brennan, a senior clinical lecturer and honorary consultant neurosurgeon at the University of Edinburgh, acknowledged there remain delays in diagnosing brain tumours because symptoms are often non-specific, with no methods currently in place for early detection of brain cancer. Consequently, 62% of patients are diagnosed in emergency departments. ‘A headache,’ he added, ‘could be a sign of a brain tumour, but it’s more likely to be something else and it’s not practical to send many people for a brain scan, just in case. The challenge is identifying who to prioritise for an urgent scan.’

The researchers say the simple blood test at this early stage could facilitate stratification of patients to be prioritised for urgent brain imaging. In a previous study, 765 blood serum samples were collected from patients diagnosed with various types of brain cancer, with three robust machine learning techniques – random forest, partial least squares-discriminant analysis and support vector machine – yielding promising results.

Image source: Shutterstock/sfam_photo

What we now have is a test that doesn’t cost very much, gives rapid results, and those who get a positive result go and get their CT scan

Paul Brennan

From blood samples from 400 patients with possible signs of brain tumour and referred for a brain scan at the Western General Hospital in Edinburgh, and patients with a recent brain tumour diagnosis, the test correctly identified 82% of brain tumours and 84% of people with no brain tumour, meaning it had a low rate of false positives. With glioma, the most common form of brain tumour, the test was 92% accurate at picking up tumours. Funded by Scottish Enterprise, the experimental study ‘Prospective clinical validation of novel serum biomarker test for the identification of patients at risk of brain tumour’ concluded: ‘This rapid screening test could revolutionise triage of patients in primary care suspected of having a brain tumour, helping to prioritise the most at-risk for rapid imaging.’

Emphasising the breakthrough would not be possible without AI, Brennan stressed this was not a case of AI speeding up a human process, but a new process that would be unavailable without AI. ‘What we now have is a test that doesn’t cost very much, gives rapid results, and those who get a positive result go and get their CT scan,’ he said.

The blood test will not replace the brain scan, which will remain a critical component for neurosurgeons to assess tumour position and type, but it could help reduce the number of patients being scanned, with earlier identification of patients potentially leading to better outcomes. ‘We are future-proofing and also providing a platform technology because the technique has the potential to be adapted to other difficult to diagnose cancers,’ Brennan added. A next step is to use the test on 600 more patients referred for a brain scan and then work with regulators, the NHS and the primary care sector towards making it available in the UK.

Brennan worked with Dr Matthew Baker from the University of Strathclyde to develop the test. Baker said: ‘These results are extremely promising because they suggest that our technique can accurately spot who is most likely to have a brain tumour and who probably does not. This could ultimately speed up diagnosis, reduce the anxiety of waiting for tests and get patients treated as quickly as possible.’

Profile:

Paul Brennan is Senior Clinical Lecturer and Honorary Consultant Neurosurgeon at the University of Edinburgh and NHS Lothian. He combines his surgical work with laboratory research into the origin of gliomas and is also active in clinical research.

20.02.2020