Drug, vaccine and surgery

Obesity is a burgeoning nightmare for everyone involved in healthcare delivery. New treatment possibilities can help to solve this probelm.

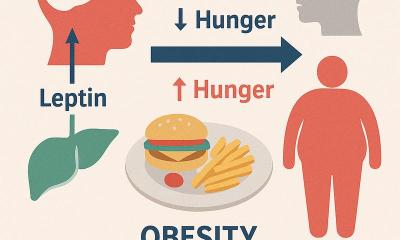

Efforts to tackle this ballooning health problem, which leads to so many others, include the development of a vaccine, as well as drugs that can reduce the appetite. Recently, for example, a drug said to control appetite by blocking activity in the brain area that regulates the body’s energy balance and ability to break down sugars and fats in the blood - and which reduced the weight of four in 10 people by 10% in clinical trials - became available in the UK, where over 1.2 million people are reported to be morbidly obese. (NB: the drug still needs approval from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), before it can become available to all National Health Service patients.)

Meanwhile, a vaccine against obesity could be in the offing. Scientists at the Scripps Research Institute, in California, have reported their development of a method to make the immune system produce antibodies that attack ghrelin, a recently discovered hormone that decreases energy expenditure and fat breakdown. Given the vaccine, fat rats ate normally yet lost weight.

However, for many who cannot respond to nutrition control and increased exercise, another possible route is surgery. The options include a gastric bypass or bariatric (or lap band) surgery. Both are laparoscopic procedures. During a gastric bypass a small stomach pouch is created and a small intestine is grafted on to it, so that food will not only bypass the stomach, but also much of the intestine.

In bariatric surgery, an inflatable band is fixed around the stomach, thus dividing it into two areas. By forming a smaller pouch at the top, less food can be taken in but the patient feels no continuing hunger. The food then moves into the lower portion of the stomach and digestion continues normally.

The band can be inflated with saline solution so that the opening to the lower chamber decreases, again increasing food restriction. Generally the band needs two adjustments, the first about six weeks after surgery.

During the recent annual meeting of the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, George Fielding MD, of the Surgical Weight Loss Programme, at New York University Medical Centre, USA, presented initial results on using laparoscopic bariatric surgery to treat obese teenagers.

Since 2001, 46 female and 12 male teenagers received lap band surgery within the programme. Their ages ranged between 13-19 years. Before the surgery, the average weight of the group was 300 pounds, and the average body mass index (BMI) was 51 kg/m2. Many suffered obesity-related co-morbidities, usually asthma, depression and dyslipidaemia.

Surgery averaged 35 minutes. Most patients were discharged within 24 hours.

There were no acute re-admissions or repeat surgery. In post-surgery follow-ups, which began three months later and continued for four years, the patients’ weight loss steadily progressed. After a year, average weight dropped from 300 to 211 pounds (average loss: 57%) and BMI had reduced by 18 points. In addition, Dr Fielding reported that, although two cases needed antidepressants, all co-morbidities resolved in that year.

The programme’s study also suggests this surgery is safe. Only two lap band slippages occurred, there was one case of leakage and two of hiatus hernia.

Also presented at the meeting, another study showed similar results from using Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery.

In this Brazilian study - involving 42 obese youngsters, aged 13-18 years, also had a several co-morbidities, which included diabetes, high serum insulin, depression, hypertension, asthma, cholelithiasis, arthropathy, and reflux disease - the average hospital stay averaged 30 hours. No intra-operative revisions were needed. There were no intra-operative complications, conversions or deaths.

48 months later, the patients’ average BMI had dropped from 45 kg/m2 to 23.5 kg/m2. Weight did not rise, nor was any malnutrition observed.

30.08.2006