Image credit: The Cancer Genome Atlas

News • Tissue sample analysis

Demographic bias creeps into pathology AI, study finds

New findings highlight the need to systematically check for bias in pathology AI to ensure equitable care for patients.

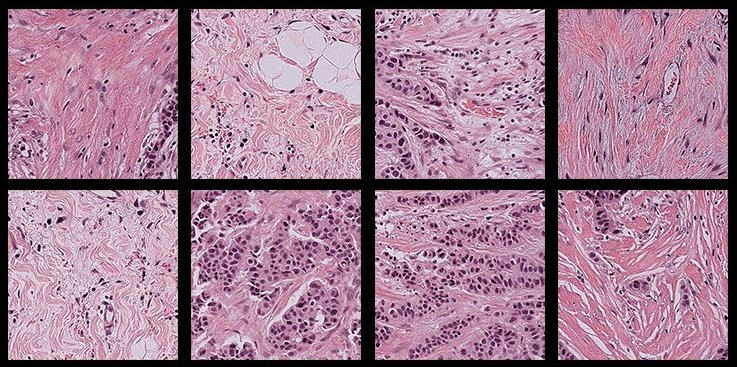

Pathology has long been the cornerstone of cancer diagnosis and treatment. A pathologist carefully examines an ultrathin slice of human tissue under a microscope for clues that indicate the presence, type, and stage of cancer. To a human expert, looking at a swirly pink tissue sample studded with purple cells is akin to grading an exam without a name on it — the slide reveals essential information about the disease without providing other details about the patient. Yet the same isn’t necessarily true of pathology artificial intelligence (AI) models that have emerged in recent years. A new study led by a team at Harvard Medical School shows that these models can somehow infer demographic information from pathology slides, leading to bias in cancer diagnosis among different populations.

The work, which was supported in part by federal funding, is described in Cell Reports Medicine.

We found that because AI is so powerful, it can differentiate many obscure biological signals that cannot be detected by standard human evaluation

Kun-Hsing Yu

Analyzing several major pathology AI models designed to diagnose cancer, the researchers found unequal performance in detecting and differentiating cancers across populations based on patients’ self-reported gender, race, and age. They identified several possible explanations for this demographic bias.

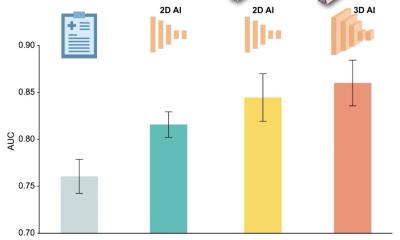

The team then developed a framework called FAIR-Path that helped reduce bias in the models. “Reading demographics from a pathology slide is thought of as a ‘mission impossible’ for a human pathologist, so the bias in pathology AI was a surprise to us,” said senior author Kun-Hsing Yu, associate professor of biomedical informatics in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS and HMS assistant professor of pathology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Identifying and counteracting AI bias in medicine is critical because it can affect diagnostic accuracy, as well as patient outcomes, Yu said. FAIR-Path’s success indicates that researchers can improve the fairness of AI models for cancer pathology, and perhaps other AI models in medicine, with minimal effort.

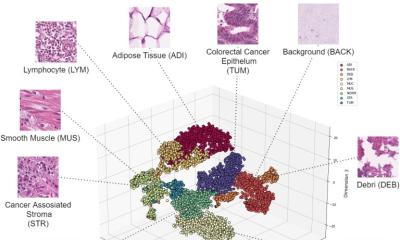

Yu and his team investigated bias in four standard AI pathology models being developed for cancer evaluation. These deep-learning models were trained on sets of annotated pathology slides, from which they “learned” biological patterns that enable them to analyze new slides and offer diagnoses. The researchers fed the AI models a large, multi-institutional repository of pathology slides spanning 20 cancer types.

They discovered that all four models had biased performances, providing less accurate diagnoses for patients in specific groups based on self-reported race, gender, and age. For example, the models struggled to differentiate lung cancer subtypes in African American and male patients, and breast cancer subtypes in younger patients. The models also had trouble detecting breast, renal, thyroid, and stomach cancer in certain demographic groups. These performance disparities occurred in around 29% of the diagnostic tasks that the models conducted. This diagnostic inaccuracy, Yu said, happens because these models extract demographic information from the slides — and rely on demographic-specific patterns to make a diagnosis.

The results were unexpected “because we would expect pathology evaluation to be objective,” Yu added. “When evaluating images, we don’t necessarily need to know a patient’s demographics to make a diagnosis.”

The team wondered: Why didn’t pathology AI show the same objectivity? The researchers landed on three explanations. Because it is easier to get samples for patients in certain demographic groups, the AI models are trained on unequal sample sizes. As a result, the models have a harder time making an accurate diagnosis in samples that aren’t well-represented in the training set, such as those from minority groups based on race, age, or gender.

Yet “the problem turned out to be much deeper than that,” Yu said. The researchers noticed that sometimes the models performed worse in one demographic group, even when the sample sizes were comparable. Additional analyses revealed that this may be because of differential disease incidence: Some cancers are more common in certain groups, so the models become better at making a diagnosis in those groups. As a result, the models may have difficulty diagnosing cancers in populations where they aren’t as common.

Recommended article

Article • Technology overview

Artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare

With the help of artificial intelligence, computers are to simulate human thought processes. Machine learning is intended to support almost all medical specialties. But what is going on inside an AI algorithm, what are its decisions based on? Can you even entrust a medical diagnosis to a machine? Clarifying these questions remains a central aspect of AI research and development.

The AI models also pick up on subtle molecular differences in samples from different demographic groups. For example, the models may detect mutations in cancer driver genes and use them as a proxy for cancer type — and thus be less effective at making a diagnosis in populations in which these mutations are less common.

“We found that because AI is so powerful, it can differentiate many obscure biological signals that cannot be detected by standard human evaluation,” Yu said. As a result, the models may learn signals that are more related to demographics than disease. That, in turn, could affect their diagnostic ability across groups. Together, Yu said, these explanations suggest that bias in pathology AI stems not only from the variable quality of the training data but also from how researchers train the models.

After assessing the scope and sources of the bias, Yu and his team wanted to fix it. The researchers developed FAIR-Path, a simple framework based on an existing machine-learning concept called contrastive learning. Contrastive learning involves adding an element to AI training that teaches the model to emphasize the differences between essential categories — in this case, cancer types — and to downplay the differences between less crucial categories — here, demographic groups.

When the researchers applied the FAIR-Path framework to the models they’d tested, it reduced the diagnostic disparities by around 88%. “We show that by making this small adjustment, the models can learn robust features that make them more generalizable and fairer across different populations,” Yu said. The finding is encouraging, he added, because it suggests that bias can be reduced even without training the models on completely fair, representative data.

Next, Yu and his team are collaborating with institutions around the world to investigate the extent of bias in pathology AI in places with different demographics and clinical and pathology practices. They are also exploring ways to extend FAIR-Path to settings with limited sample sizes. Additionally, they would like to investigate how bias in AI contributes to demographic discrepancies in health care and patient outcomes.

Ultimately, Yu said, the goal is to create fair, unbiased pathology AI models that can improve cancer care by helping human pathologists quickly and accurately make a diagnosis. “I think there’s hope that if we are more aware of and careful about how we design AI systems, we can build models that perform well in every population,” he said.

Source: Harvard Medical School; by Catherine Caruso

22.12.2025