Image source: Rigshospitalet

News • Immune system insights

New corona research could improve vaccination techniques

New research from Copenhagen University Hospital – Rigshospitalet and Herlev and Gentofte Hospital has shed new light on the immune system’s complex struggle against the coronavirus.

The research has been published in the journal Nature Communications and it could be an important guide for how populations and communities should protect themselves against the virus when the next pandemic strikes.

The VACCIM study completed in-depth analyses of immune responses after vaccination against Covid-19. The data was extracted from around 3,000 hospital employees who, during the Covid pandemic, gave blood samples so that researchers could monitor their immune response to infection with Sars-CoV-2 and vaccines.

The variation in the immune response became considerably more complex over time, because people were infected with different variants of Sars-CoV-2 and at different intervals between vaccinations

Laura Pérez-Alós

The new data reveals significant variations in the immune response after vaccination, depending on the time of the vaccination, previous natural infections, and the variant of coronavirus a patient is infected with. The first author of the study, PhD student Laura Pérez-Alós from the Department of Clinical Immunology at Copenhagen University Hospital explained: "Our results show that some individuals are at greater risk of being infected or being re-infected. Participants in the trial had a significantly increased risk of infection with Sars-CoV-2 if they had low levels of antibodies after vaccination. Specifically, we examined the risk of infection with the Omicron variant, but the variation in the immune response became considerably more complex over time, because people were infected with different variants of Sars-CoV-2 and at different intervals between vaccinations," said Laura Pérez-Alós.

Recommended article

Article • Covid-19

Coronavirus update

Years after the first outbreak and spread of coronavirus Sars-CoV-2, its impact can still be felt in everyday life. Keep up-to-date with the latest research news, political developments, and background information on Covid-19.

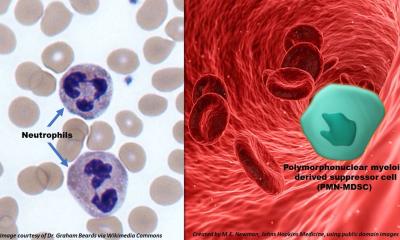

Researchers measured two types of antibodies, IgG and IgA, as well as the ability of T cells to respond to the virus. IgG is primarily found in the blood and it has an important role in neutralising the Sars-CoV-2 virus. IgA is primarily found in the mucous membranes, for example in the nose and lungs, and levels of IgA antibodies typically rise after infection. Although levels of IgG and IgA were very significant for the risk of repeat infections, the researchers could not find the same link between T-cell response and the risk of infection. However, several studies have shown that T cells protect against serious Covid-19 illness, whereas antibodies are important for transmission of the virus, and thereby infection.

It is currently unclear how long immunity from T cells protects against serious illness after vaccination. However, research indicates that T-cell immunity is less affected by changes in the virus over time than observed for antibodies. The head of the researcher team, Peter Garred, professor and chair in clinical immunology at the University of Copenhagen and a consultant at Copenhagen University Hospital explained: "Our study shows that the responses of both antibodies and T-cells after vaccination were generally higher if participants had been infected with Sars-CoV-2. However, although we have previously demonstrated that the level of antibodies falls drastically over time, we can also see that a booster shot can increase the level of antibodies to the same or even a higher level than before".

A deeper understanding of how the time of infection and vaccination affects our immune response means we're better equipped to handle future threats and ensure more effective protection for all

Peter Garred

A crucial discovery in the study is the relationship between the original Wuhan variant and reinfection with the Omicron variant. If a person was initially infected with the original Wuhan variant and then with Omicron, the immune response was weaker than if infection was only with Omicron. This phenomenon is known as “immune imprinting" and it has previously been observed in flue epidemics.

“Think of your immune system as a kind of camera with a memory. When it “sees" a virus, it takes a “photograph" and saves it. The next time you meet the same virus or a variant of the virus, your immune system looks in its “photo album" to decide how to react. The challenge with immune imprinting is that the immune system can be so taken up by the first "photograph“ that it is difficult to recognise and react effectively to a new version. This knowledge is important to understand why we can become infected and ill again when new variants of coronavirus appear. It also underlines the need to consider very carefully what versions of the virus we include in future vaccines to ensure optimal protection," said Peter Garred.

Data from Statens Serum Institut (SSI) shows a significant increase in infection rates in Denmark at the moment, and according to Peter Garred it is very likely that we are looking at an autumn and winter with a high infection rate. The new Sars-CoV-2-variants give lower risk of severe illness than previously, but they are more contagious.

"We have a population with relatively good immunity due to vaccination and previous infection, which is currently overshadowing the phenomenon of "immune imprinting". Unfortunately, some citizens are more exposed to severe illness requiring hospitalisation, particularly the elderly and immunocompromised. These individuals will have great benefit from a booster shot balanced between the original Wuhan variant and the new Omicron variants. The research underlines the importance of regularly examining and adjusting vaccination strategies, particularly in light of new variants. A deeper understanding of how the time of infection and vaccination affects our immune response means we're better equipped to handle future threats and ensure more effective protection for all," said Peter Garred.

Source: Copenhagen University Hospital – Rigshospitalet

10.10.2023