And then there was light!

Pin-sharp outlines instead of a flurry of speckles, three-dimensional bodies instead of two-dimensional cross sections: Modern ultrasound scanners now deliver images of a quality that would have been inconceivable just a few years ago. This new generation scanners have made ultrasound diagnostics more reliable, reproducible and much easier to use for doctors

Not so long ago medical imaging enthusiasts claimed ultrasound was a dying species. It’s not so surprising. A decade ago, trying to achieve an image of the gallbladder with ultrasound would have resulted in a ‘hurricane’ of undesired pixels – known as speckle noise. However, today’s generation of scanners do not suffer from this problem. At most there may be a few individual speckles, but the examiner now sees an anatomy almost unspoilt by artifacts.

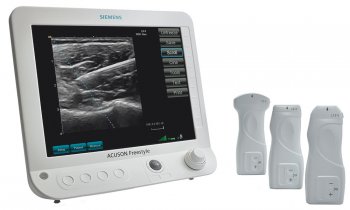

‘We’ve moved well away from the old speckled ultrasound images,’ says Dr Thomas Fischer of the Ultrasound Laboratory at the Charité in Berlin. ‘These days, ultrasound is the imaging procedure with the highest resolution. It delivers images of tremendous quality.’ The technical foundations for this are manifold. The key words are tissue harmonic imaging, compound imaging, speckle reduction and spatial filtering. ‘Compound imaging, which used to be reserved for highend machines, is now also available for our base model Accuson X300,’ Alexander Stanke, Head of Ultrasound Germany at Siemens points out. Philips also provides this technology with their basic range model HD7.

Compound imaging means that images are taken from different directions to reduce speckling. This requires changes to the software as well as the transducer.

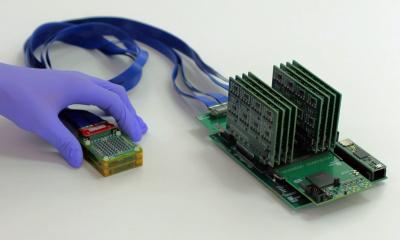

The transducer (probe) is the essential part in modern ultrasound imaging: ‘New probes, which we are already using with upper end midrange scanners, use directed crystals,

which are produced in a similar way to computer chips,’ says Ludwig Isken, Product Manager Ultrasound at Philips Healthcare. Rather than 40%, these probes transform 80% of electric energy into mechanic (ultrasound) energy. ‘This reduces the energy consumption and

allows for entirely new design of the probes.’

The difference in image quality achieved by these and other innovations is now visible in almost every organ. Looking at the kidneys, for example, we can now see an organ where the cortex and the parenchyma are very clearly defined. In case of the liver, the modern scanners can detect lesions despite fatty liver. ‘And, in the case of the right lower abdomen we can now differentiate between appendicitis and an infection of the terminal ileum via ultrasound,’ Dr Fischer adds.

That last example clearly shows that better images are not just an end in itself but result in improved patient care. Whether appendicitis or an infection of the terminal ileum is present makes a big difference to treatment. In one case, the abdomen has to be opened and, in

the other, it remains closed. It’s no wonder that the National Association of Statutory Health

Insurance Physicians has implemented a so-called ultrasound agreement for the improvement of diagnostic quality in out-patient medicine. This is a quality assurance

measure that regulates the prerequisites needed for doctors to carry out, and charge for, ultrasound examinations, and also regulates the equipment itself, because it has to meet certain technological standards to remain useable in the future.

Against this background, many doctors practicing outside hospitals are faced with the decision of acquiring a new ultrasound scanner – and therefore with the question of which one they should choose. If you want to spend less than €10,000, you very much get what you pay for.

‘At the cheapest end of the market customers often can’t rely on good equipment and service quality,’ says Dr Hans Worlicek, a gastroenterologist from Regensburg and expert for outpatient care at the German Society for Ultrasound in Medicine (DEGUM). Dr Worlicek recommends spending a little more: ‘Efficient, basic scanners can be purchased for around €15,000. Mid-range scanners cost between €20,000 and €40,000.’ In this range, doctors get quite a lot for their money. What this looks like is something that visitors can discover at Medica 2010 in great detail, as ultrasound diagnostics is yet again one of the show’s big features. ‘We offer customers in private practice many automated measurements that work with knowledge databases in the background and reduce the amount of work required significantly,’ Dr Stanke points out. With just a few markings gynaecologists, for instance, can measure head circumference and foetal spine length and automatically view the length of a

pregnancy and other information. ‘There is a similar application for internal medicine, where we offer an arterial health package for self-funded examinations,’ he adds.

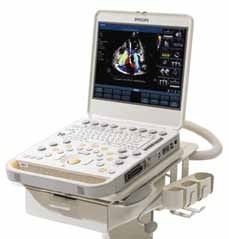

The equipment calculates cardiovascular risk according to Framingham based on the intimamedia thickness. This technology also includes a service package. Siemens is introducing a 0% finance package at Medica that will make the acquisition of new scanners more calculable. Additionally, the company offers accident and breakdown cover, which protects the equipment against outages. Philips is focusing on user ergonomics at Medica. Even the firm’s basic scanners, such as the HD7, already have a button for automatic image optimisation. Called iScan, it replaces the manual control. ‘This saves time, reduces user errors and makes the results reproducible,’ says Ludwig Isken. There are also some other simple features that ease everyday life. ‘Almost all scanners these days come with flat

screens, which means you can still see even if the surroundings are very bright,’ Hans Worlicek points out. With the old machines on the other hand, ultrasound is still something that almost needs to be carried out in a darkroom.

19.11.2010