Article • Neuroradiology

Alzheimer’s research: A lost century

Lack of understanding around Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has significantly slowed advances in the treatment of this incurable condition.

Report: Mélisande Rouger

Imaging has proved to be reliable in differentiating between AD and other forms of dementia, and its contribution will continue to help develop profiling, an increasingly interesting approach for the development of new and more efficient drugs, according to Sven Haller, a Swiss neuroradiologist, who spoke during EuSoMII’s annual meeting, held last October in Valencia, Spain.

A history of lateness and misunderstandings

Over a century of research in AD treatment has failed to cure people. For this, there are two main reasons, according to Haller, who will chair the New Horizons session on ‘Alzheimer's disease and neurodegeneration: visualising the invisible’ during this year’s European Congress of Radiology (ECR). ‘Giving therapy to only patients with clinical symptoms of dementia has greatly impacted on therapeutic advances. For 80 years, we’ve given drugs to patients who already had symptoms. However, we know that if we wait for symptoms to develop, by then 50% of the neurons are lost.’ This was already confirmed in a study from 1968. ‘Even if the medication works, it will very likely not revitalise dead neurons,’ he explained.

Another major setback has been the profound misunderstanding of Alzheimer’s disease, which is a form of dementia. There are many types of dementia, for example vascular dementia, a group of frontal dementias and Lewy Body dementia, among others. Alzheimer’s and dementia are not the same, but they are commonly perceived as such, Haller pointed out. ‘You don’t have one stereotypical form of dementia. Not everybody who has dementia has AD. If you simply treat a person with signs of cognitive decline with AD medication, it may just not work, as this patient may not have Alzheimer’s disease,’ he said. To complicate matters further, there are also different disease subgroups of AD, which must be tackled independently. Drug development must take this diversity into account, because there will not be ‘a magic universal drug that will work in all patients with dementia,’ he stressed.

Recommended article

Article • MRI vs. Alzheimer's

Seeking leaks in the blood-brain barrier

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) separates blood from the brain tissue and protects the brain by allowing certain substances to pass while keeping others out. Walter H Backes, with his interdisciplinary team of Maastricht UMC and Leiden UMC, are hot on the tracks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) as they aim to visualise small vessel leakage in BBB.

Imaging central to early diagnosis and differentiating

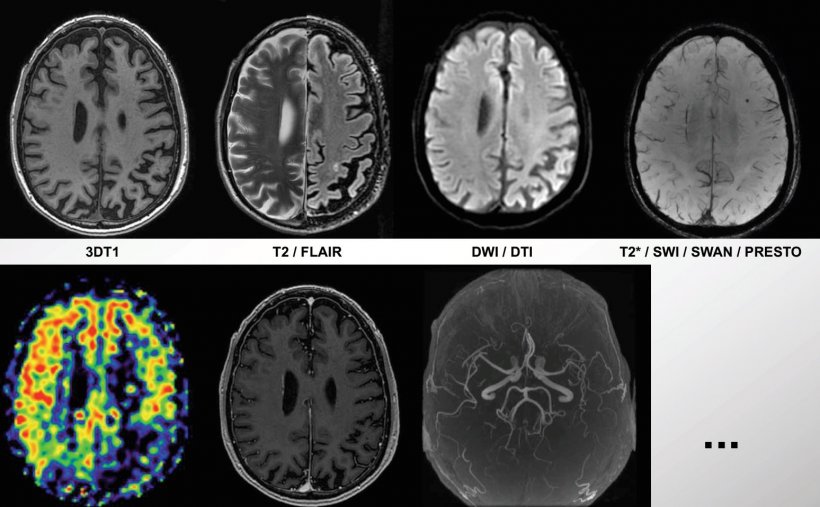

Medical imaging is needed for early and specific identification of patients at risk of a specific type of dementia before the onset of clinical symptoms. Imaging is a great way of assessing and differentiating dementia, which can further help to develop adequate medication for each disease and subgroup. ’Imaging is, in my opinion, quite a lot of parameters that you can assess: atrophy, which is a marker of neurodegeneration; perfusion, a marker of brain function, and a different range of markers of vascular disease.’

Imaging is very useful to diagnose patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) at an early stage. However, this is not enough. ‘Approximately half of unselected MCI will remain stable even without intervention,’ Haller explained. ‘In the MCI group, you must detect those who will likely deteriorate later on.’

The typical pharmaceutical trial including unselected MCI cases will include approximately 50% of stable MCI patients, half of whom will get placebo and the other half will receive treatment. ’This means only 25% of MCI cases will progress and get the true medication, while 25% of MCI cases remain stable despite being in the placebo group. That’s one of the many reasons it’s so difficult to detect a treatment effect.’

Appeal for a more faceted approach

We should include the assessment of the entire pattern of atrophy of the whole brain, which is much more specific than looking only at the hippocampus

Sven Haller

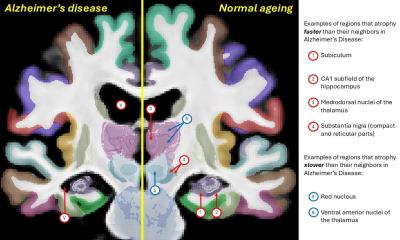

Most studies focus on hippocampal atrophy alone, the known imaging hallmark of dementia. However, hippocampal atrophy is not specific to AD – it also occurs in other types of dementia, e.g. frontal dementia. And not all cases with a mild degree of hippocampal atrophy will develop dementia. ‘We should therefore include the assessment of the entire pattern of atrophy of the whole brain, which is much more specific than looking only at the hippocampus. Moreover,’ Haller added, ‘we should add into the equation markers of vascular disease, brain function etc., as discussed above.’

Radiologists should watch out for the obvious. Intuitively it is obvious to assume a linear correlation between more atrophy and worse clinical symptoms. However, in reality it is much more complex. There is a cognitive reserve or brain reserve. The same amount of measurable atrophy may be associated with a very large variability of cognitive decline at the individual level, depending on the cognitive reserve, social integration, education, activity in daily life, nutrition etc. ‘We should not simply assume that a case with, for example, moderate hippocampal atrophy will inevitably also have moderate clinical symptoms of dementia. The situation is significantly more complex.’

Getting early diagnosis is key and profiling is an interesting strategy. In Europe, trials are on-going that run tests to assess risk factors, family history and genetics for preselection of high-risk people for drug trials, for example the European Prevention of Alzheimer's Dementia Consortium (EPAD). ‘A lot of work remains to be done, but if efforts are put to good use and properly targeted, we could make big leaps in AD and dementia treatment in the near future,’ Haller concluded.

Profile:

Sven Haller, visiting professor at the University of Uppsala, Sweden, and neuroradiologist at the Centre d’Imagerie Rive Droite (CIRD) in Geneva, Switzerland, follows a special interest in advanced neuro-imaging techniques, particularly advanced MR techniques including functional MRI, real-time functional MRI neurofeedback and arterial spin labelling (ASL), notably in the domain of neurodegenerative and neurovascular diseases. His scientific awards include the Lucien Appel Prize (2011; European Society of Neuroradiology); Founders Award (2009; European Society of Neuroradiology); the Jubilee Prize (2009; Swiss Society of Radiology); Kurt Decker Prize (2014; German Society of Neuroradiology); and, twice, the Peter Huber Prize (2004 and 2009; Swiss Society of Neuroradiology. He is also section editor for advanced imaging in Neuroradiology, the official journal of most European Societies of Neuroradiology, and section editor for neurodegeneration in the new textbook of Neuroradiology from the European Society of Neuroradiology.

19.08.2020